What is the scope of the India-Taliban relationship?

Summary:

In November, there were reports that the Afghan embassy in New Delhi will be shutting down. This was followed by a statement from the Taliban: consular activities would resume shortly.

This back-and-forth over the embassy is the latest in an ongoing tussle over the control of the Afghan mission. This issue stems from the rise of the Taliban, the group that captured power in Afghanistan in August 2021.

The Taliban’s return to power in Kabul has led to greater engagement between the group and the Indian government. The question is: what is the scope of India’s engagement with the Taliban?

In this article, I analyze the Indian government’s initial response following the Taliban’s rise to power in 2021 and parse the debate on engaging the group.

I argue that the Indian government should consider further supporting Afghan students, continue engagement with other Afghan actors, and conduct an inquiry on its Afghanistan policy to ensure that it maintains ties with the Afghan people while securing its interests.

Note to readers: If you have just come across Indialog, consider reading my previously authored articles on India & the G20, the democratization of Indian foreign policy, India’s military expenditure, measuring geopolitical risk, and India-Pakistan ties. If you find value in any of these articles, please do share, and subscribe to, the Indialog.

Introduction:

On November 23, a statement from the Afghan embassy declared that its mission in New Delhi was shutting down. A few days later, on November 29, the Hindu reported that the Taliban had “Delhi’s tacit approval” to restart the Afghan embassy. This was followed by Afghan diplomats stationed in India who expressed “willingness to continue consular work even in the absence of representatives of the pre-Taliban government of President Ashraf Ghani.” A Taliban-appointed acting minister similarly noted that the Afghanistan mission in New Delhi will resume activities shortly. This is the latest in an ongoing tussle over the control of the Afghan mission.

When a version of this “power struggle” was unfolding at the Afghan embassy in June 2023, an official for India’s Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) noted that the issue was “an internal matter of the Afghan Embassy.” The Indian government hoped that the issue would be resolved “internally.” The Indian government’s response is at odds with reports that claim pressure on the Afghan embassy from “the Taliban rulers in Kabul as well as the Government of India,” to cease operations so that the Taliban could operate the embassy.

There is limited public information about what transpired with the embassy. What is clear is that the Indian government has been engaging with the Taliban in some form, ever since the group captured power in Kabul. This leads to a broader question about India’s actions that needs to be asked. What is the scope of the Indian government’s engagement with the Taliban?

In the following piece, I will briefly analyze the rise of the Taliban in 2021 alongside India’s initial response to developments in Afghanistan. I will then assess the debate on engaging the Taliban. As I make clear, there are few good options in Afghanistan, and engagement with the Taliban may be critical to at least ensure that Afghan citizens’ suffering is minimized. I conclude with a few suggestions for Indian policymakers as they reassess their Afghan policy.

Taliban’s rise in 2021 and India’s initial response:

The Taliban stormed to power on August 15, 2021, surprising many across the globe, including themselves [see Fig. 1]. The idea that the Taliban would eventually rise to power in some form was broadly taken for granted following the 2020 Doha deal. The inevitability of the Taliban’s rise gained momentum as major cities fell to Taliban rule one by one in the summer of 2021. Yet, the speed with which the Taliban took over Kabul was shocking.

India’s initial response included closing its Afghan consulates, followed by shuttering its embassy in Kabul, and evacuating its staff and Indian citizens, as it reassessed the situation on the ground.

There were justified security concerns, alongside questions about what a Taliban rule in Afghanistan would entail. In a meeting between India’s ambassador to Qatar and the Taliban in August 2021, the ambassador conveyed “India’s fears that anti-India militants could use Afghanistan’s soil to mount attacks.”

Even as some of the security-related concerns remain, there have been some signs for a while that point to slow, but steady, engagement with the Taliban. What are these signs? Fig. 2 charts a timeline of select interactions between the Indian government and the Taliban and key Indian initiatives on Afghanistan. As Fig. 2 demonstrates, overt interactions have primarily been on security grounds and to ensure the provision of humanitarian aid to Afghans.

Fig. 2. Key Afghan-related initiatives & select interactions between the Indian govt. and the Taliban

Debating engagement with the Taliban:

This isn’t the first time Indian officials are engaging the Taliban. As Avinash Paliwal illustrates in his book My Enemy’s Enemy: India in Afghanistan from the Soviet Invasion to the U.S. Withdrawal, there has been a long-standing debate within India’s security community on engaging the group. In Paliwal’s assessment, when the Taliban previously rose to power in the 1990s, those who advocated for engagement with the Taliban lost out to those who advocated against it.

The return of Taliban rule in Kabul, two decades after the group last exercised power, has occurred at a time of significant change in the international, and South Asian, landscape. With the return of the Taliban, there has also been a willingness on India’s part to engage with the group.

In 2020, the United States, eager to end the war in Afghanistan, signed a ‘peace agreement’ with the Taliban, promising the eventual withdrawal of U.S. and NATO forces. Even then, experts pointed to the “flawed deal,” noting that a withdrawal could allow the Taliban “to regain control.” However, the United States, tired of a two-decade long war, had arranged its exit.

As it slowly became clear that the Taliban would return in some form, India covertly interacted with the group. After their return to power in Kabul, an Indian ambassador met with representatives of the group in Doha. Subsequently, an official MEA spokesperson reiterated the fact that India has been in contact with all stakeholders [emphasis added] when asked about potential back-channel dialogue with the Taliban [16:00 – 16:28 m].

Since the Taliban’s rise to power, Indian engagement with the Taliban has ostensibly been on the grounds of delivering humanitarian aid. However, there is a clear security angle to this engagement. A long-standing concern for the Indian security establishment has been the risk of terrorism emanating from the region, with the Taliban providing support for such attacks against India and factions within the Taliban, such as the Haqqani group, directly targeting Indian assets.

In addition to the Taliban, the emergence of actors such as the Islamic State in Afghanistan has added to tensions about terrorism in the region. As a 2022 attack by the Islamic State on a Gurudwara (Sikh place of worship) in Kabul demonstrates, terrorism-related risks are genuine.

Furthermore, the Taliban’s deep relationship with Pakistan has been a serious cause of worry. Some signs point to cracks within the Pakistan-Taliban relationship – recently, Pakistan’s special representative to Afghanistan noted that “peace in Afghanistan” had become a “nightmare for Pakistan” as militant groups inimical to Pakistan strengthened after the Taliban’s return to power. However, despite turbulence in the Taliban-Pakistan dynamic, India’s concerns about this nexus have historically determined its Afghan policy.

Then there is the moral issue of engaging with a group that places severe restrictions on women’s rights, including their access to education, curtails the freedom of expression, and conducts extrajudicial killings and public executions.

Given India’s many concerns, and fears about being absent in the region (as it was the last time the Taliban was in power from 1996 to 2001), engagement appears to be one of the few choices India has. As I lay out in Fig. 2, India is engaging with the Taliban.

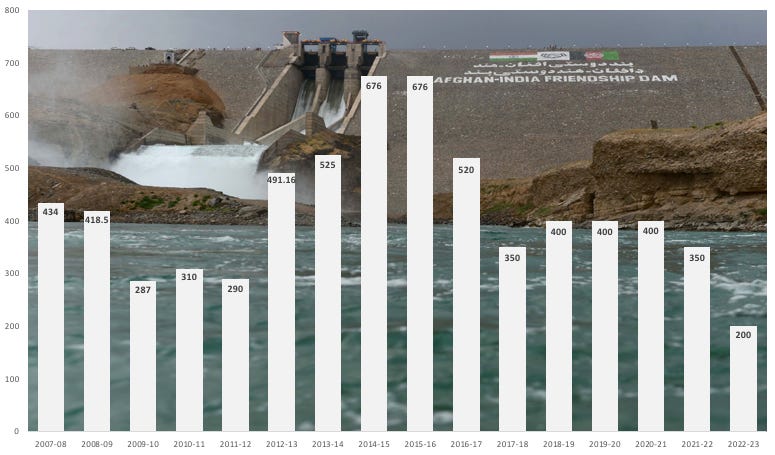

Dealing with the Taliban is a vexatious issue. For India, which has invested significantly in Afghanistan and its people [see Fig. 3], not engaging with the Taliban would mean ceding ground in the region. This could have significant repercussions, including impacts on the developmental work India has already undertaken in the region and adverse consequences for regional security. Furthermore, if India chose not to engage with the Taliban, there could be concerns around humanitarian assistance – would aid from India reach the Afghan people, the way it is intended to?

There are no easy answers, and India is not alone in having to negotiate with this issue. As analysts for the International Crisis Group highlight, governments across the world are unsure about how to deal with the Taliban. The U.S. and some of its Western partners have tried to use aid conditionality and sanctions to moderate the Taliban’s behavior to highly questionable effects. A former U.S. ambassador to Afghanistan argued that his country’s approach “of sanctions, demands, and restricted contact with the Taliban is not working.” A June 2023 Congressional Research Service report underlined the “Taliban’s evident aversion to make compromises in response to international pressure and its apparent willingness to accept considerable humanitarian and economic suffering in Afghanistan as the price of that uncompromising stance.”

The question of whether, and how, to engage with the Taliban has also vexed scholars with considerable Afghanistan expertise. Responses to Foreign Affairs’ question ‘Should the United States Normalize Relations with the Taliban? demonstrates the range of varying opinions on this issue.

What is noteworthy is that even Afghan citizens who have had to flee the country, and work on humanitarian matters, point out that if there is no engagement with the Taliban, Afghan citizens will suffer the most. An Afghan woman’s rights activist emphasizes the fact that “there is no viable alternative to them [the Taliban]” in the country. Scholars demonstrate that Western pressure tactics are not working, and on the contrary may worsen the situation, further pushing the “regime toward isolation and radicalization while complicating human rights monitoring.”

As Sahar Fetrat (a researcher with the Women’s Rights Division at Human Rights Watch) notes, “without a conversation, without involvement, without engagement, we will be punishing the people of Afghanistan.” A policy maker, previously with the Ghani government, and now working with a major humanitarian organization on the ground in Kabul underscored the same message to me. Analysts have recommended that while dealing with the Taliban might be difficult, “there is no good option in Afghan policymaking.” Similarly, others have argued that donors will have to work with the Taliban if they are to effect change on the ground.

The way forward for India:

It is clear that India, bereft of any good options in Afghanistan, is engaging the Taliban. The question is: what is the scope of this engagement? Equally important, what steps could the Indian government take as its Afghanistan policy changes? Some analysts, such as Fetrat, suggest that governments could consider adopting a position of ‘principled engagement.’ This could be read as engagement not for the sake of engaging, but rather to moderate the Taliban’s policies at the margins while ensuring one’s interests are protected. However, the idea of ‘principled engagement’ in an Indian context needs to be fleshed out with clear goals in mind.

Beyond this, the Indian government could consider taking three steps to preserve its ties in the region even as it reevaluates its position concerning the Taliban. These steps include supporting Afghan students, continuing engagement with non-Taliban Afghan actors, and conducting an internal inquiry into the Taliban’s rise as India reassesses its Afghanistan policy.

Supporting Afghan students: That the Afghan people have suffered tremendously in the past two years is a fact. In light of this, India’s policy of not supporting Afghan students interested in studying in India, and those already in the country needs to be revisited. India has justified security concerns emanating from the region, but given its state capacity, surely there are creative ways through which the government could ensure that Afghan students are supported. Even measures such as extending scholarships will come as a respite to Afghan students. In an article, I listed several ways through which India can support the next generation of Afghans. I have previously advocated for extending help to Afghan students; this point can’t be overstated.

Continuing engagement with Afghan actors: Countries around the world, including India, have emphasized the importance of an ‘inclusive’ government in Afghanistan. For the Taliban, inclusivity ranges from “broader participation in governance (which they are willing to consider, at least for men) to inclusion of political figures from the defeated government (which they are not).” What does an inclusive government mean for the Indian government? This is a question that needs to be addressed by Indian officials. Furthermore, India can highlight that engagement with non-Taliban actors is only a return to its status-quo policy of speaking with all stakeholders in the country.

Conducting a reassessment of India’s Afghanistan policy and an inquiry into the Taliban’s rise: The Taliban’s rise to power in Kabul in some form was taken for granted following the signing of the 2020 Doha deal. Yet, the speed with which the Taliban captured power was surprising to many, as highlighted above. The timing of India’s shuttering of its consulates and embassy, its initial outreach to the Taliban, and remarks by an MEA spokesperson indicate that the Indian government, like other states, was caught unaware of how quickly the Afghan political landscape will change.

Given the change in power in Kabul, and a perceptible shift in India’s policy on engaging with the Taliban, it might be in the government’s interest to conduct a wholesale reassessment of India’s Afghanistan policy. Why could the Indian government not foresee the rapid change that would befall Afghanistan? How can the Indian government ensure that its interests are protected under a Taliban-ruled Afghanistan, even as it maintains its long-standing ties with the Afghan people? Such an inquiry could also consider any intelligence deficiencies that might have resulted in India being slow to understand the pace of the Taliban’s rise. Several countries, most notably the United States, have instituted inquiries to determine their role in Afghanistan, and others have set up special immigration and refugee measures to address Afghanistan’s humanitarian issues.

It is clear that India is playing the long game in Afghanistan and can’t afford to be absent the way it was the last time the Taliban was in power. With these factors in mind, the Indian state needs to be proactive in its relationship with Afghanistan. As can be observed, the Indian government has determined that some form of engagement with the Taliban is necessitated given the ground realities in Afghanistan. The question for analysts is – what is the scope of India’s engagement with the Taliban? While the government may have to deal with the group, there are certain red lines the Indian government won’t cross. These red lines possibly include recognizing the group or allowing a Taliban flag in Afghan missions on Indian soil.

What is certain is that the Indian government will continue engaging with the Taliban as long as India’s interests are protected, and the group remains in power. Even as India’s Afghan policy changes, hard questions need to be asked, and where possible answered, concerning these policy changes. As I previously argued, for a nation that constantly emphasizes its “civilizational relationship” and “historical connect” with Afghanistan, India can – and should – do more to assist Afghans.

Links:

On climate policy: COP28 is currently underway, and the climate summit began proceedings with “delegates adopting a new fund to help poor nations cope with costly climate disasters.” Read this Bloomberg piece by Akshat Rathi on the ‘loss and damage’ fund. To better understand what the ‘loss and damage’ fund is, who will oversee it, and other related practicalities, read this well-explained Carbon Brief Q&A.

Lee Beck, David Yellen, and Noah Gordon have an article on some of the broader geopolitical trends that will be driving climate action going forward. While the future appears bleak, the authors remind readers (and policymakers) that “foreign policy and economic policy are climate policy.”

This curtain-raiser by Navroz Dubash, for The Hindu, helped me understand the key drivers for climate policy going into COP28.

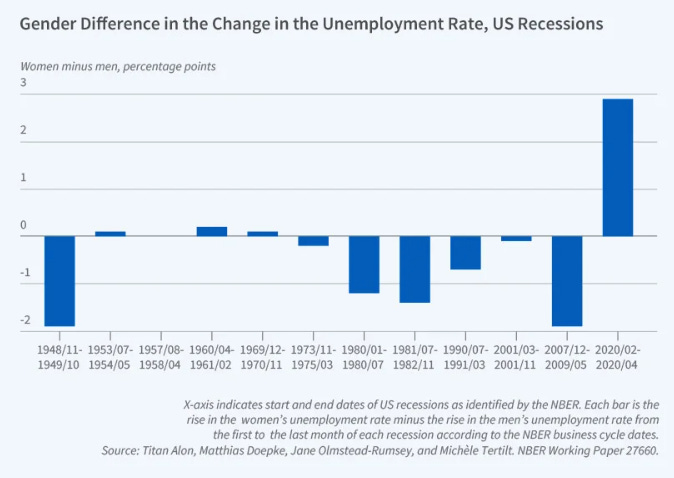

On employment & recessions: A recent NBER article by Dr. Matthias Doepke shows that the pandemic recession of 2020 had a “disproportionate impact” on women’s employment. In all U.S. recessions since 1949, men’s unemployment rates increased compared to women’s. As the data show, “in contrast, in the pandemic recession of 2020 women experienced a sharper rise in unemployment.” This is all the more striking as “at the height of the recession, hundreds of thousands more women than men were unemployed, even though 10 million fewer women than men were in the labor force.”