Security in Numbers: India-Pakistan Ties & Ceasefire Violations

Summary:

The Security in Numbers series highlights and analyzes data, shedding light on numbers and issues that are critical to Indian national security.

This edition focuses on the state of India-Pakistan ties. This month marks two decades since the 2003 ceasefire agreement. The agreement is, arguably, one of the strongest measures taken by the two states to further peace in the region.

While the agreement reduced the number of ceasefire violations along the border for a few years, violence has risen in the past decade. Studying the levels of ceasefire violations sheds some light on how bilateral ties are faring.

Introduction:

This month marks two decades since the 2003 ceasefire agreement between India and Pakistan. Since their independence in 1947, the two nations have been engaged in a rivalry. The history is not solely one of competition. However, the root causes of conflict remain unresolved. Of all the steps taken to further peace in the region, the 2003 agreement arguably represents one of the strongest efforts since the turn of the century.

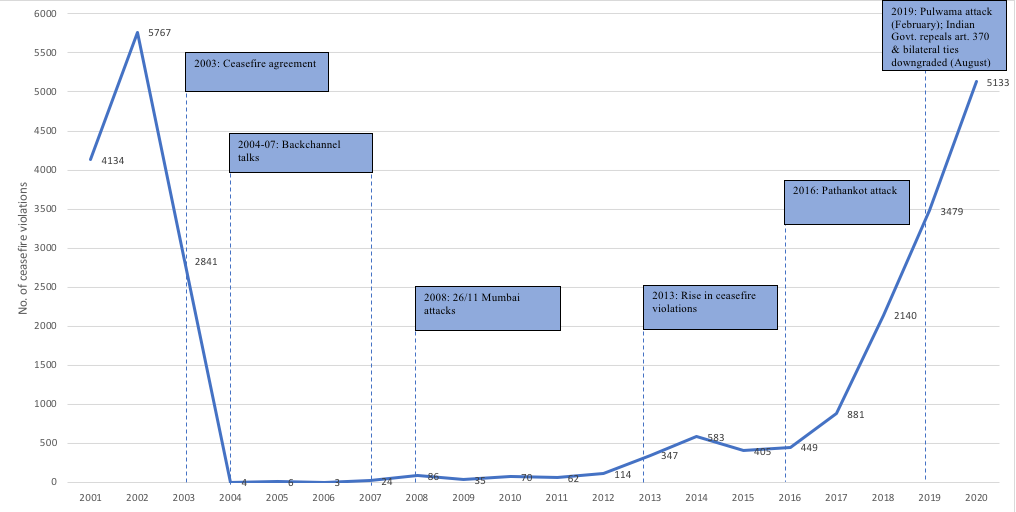

The 2003 agreement led to a few years of relative peace along the border. This agreement occurred alongside back-channel talks from 2004 to 2007 that came very close to resolving a host of bilateral issues. One of the most direct results of the 2003 agreement was the calm along the heavily militarized borders that otherwise saw frequent firing (there were 5767 ceasefire violations in 2002 according to official Indian sources) resulting in the deaths of soldiers and civilians.

State of India-Pakistan ties:

Two decades since the 2003 agreement, what is the current state of India-Pakistan ties? A recent Economist report quoted an Indian official stating that “no one is thinking about Pakistan.” This attitude on India’s part can be ascribed to several factors – most notably, Pakistan’s relative decline (see Fig. 1) that has altered the contours of the bilateral relationship.

There is, in all likelihood, limited appetite in India to engage with Pakistan, as peace-building attempts over the past decade have often been thwarted with terrorist attacks occurring close on the heels of conciliatory steps. The 2004-07 back channel faltered for a host of reasons – key among them was the loosening of President Musharraf’s grip on power. The 26/11 terrorist attacks in 2008 halted peace efforts for a while. As Christopher Clary notes in his recent book on India-Pakistan ties, Indian Prime Minister Modi’s outreach in 2014 and 2015, were followed by the Pathankot terrorist attacks in early 2016. The 2016 attack, Clary notes, “began a cycle of repeated crises, where the relationship remains today.”

After India repealed provisions under Article 370 of the Indian constitution that “granted a special status” to Jammu and Kashmir in 2019, the two nations downgraded diplomatic ties and suspended bilateral trade. In 2021, India and Pakistan reaffirmed the 2003 ceasefire agreement. An Indian press release announcing the joint statement noted that “both sides agreed for strict observance of all agreements, understandings and cease firing along the Line of Control and all other sectors.” As a former Indian Ambassador to Pakistan noted, both India and Pakistan realized by early 2021 that it was not in their respective interests to allow tensions to fester along the border. Scholars have also pointed out how an evolving security landscape (border clashes between India and China in 2020) may have created conditions for potential rapprochement between India and Pakistan.

Reaffirming the 2003 ceasefire agreement in 2021 has reportedly eased tensions along the border following a large number of ceasefire violations in 2020 (the highest since 2003; see Fig. 2). However, the freeze in bilateral ties continues. In May 2023, Pakistan’s then Foreign Minister Bilawal Bhutto Zardari was in India for a meeting of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). One of the highest-ranking Pakistani officials to visit India in years, the meeting saw sharp exchanges between Indian and Pakistani officials. If his visit is indicative of the state of ties, there appears to be limited scope for dialogue between India and Pakistan.

Ceasefire violations:

One way to understand the state of India-Pakistan ties is to look at the number of ceasefire violations occurring along the border. Happymon Jacob, a scholar who has written a book on ceasefire violations and escalation dynamics, highlights the reasons attributed to ceasefire violations by the two states. India argues that ceasefire violations occur because “the Pakistani military provides covering fire to terrorists infiltrating the Indian side of the region,” whereas Pakistan “blames India for unprovoked firing targeted at the civilian population on the Pakistani side of the LoC [Line of Control].”

While there are many reasons for ceasefire violations, as Jacob painstakingly highlights, the increase (and decrease) in these violations is in a way indicative of the state of ties. In the years after the 2003 ceasefire agreement, there was a substantial decrease in violations (see Fig. 2). As ties have deteriorated, the number of ceasefire violations has substantially increased. After India and Pakistan reaffirmed the 2003 ceasefire agreement in February 2021, the number of violations in the following months reduced drastically (see Fig. 3; MHA data).

Way forward:

Even as India and Pakistan reiterated their commitment to the 2003 ceasefire agreement in 2021, there have been no public moves towards dialogue. Both states argue that it is up to the other to create the right conditions for talks. In its latest annual report, India’s Ministry of External Affairs states “India desires normal neighborly relations with Pakistan. India’s consistent position is that issues, if any, between India and Pakistan should be resolved bilaterally and peacefully, in an atmosphere free of terror and violence. The onus is on Pakistan to create such a conducive environment” [emphasis added]. Recently, then-Pakistani Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif stated that Pakistan was ready to talk to India and the Pakistani Foreign Office spokesperson added that “we believe the ball is in India’s court to create an environment for peace and dialogue” [emphasis added]. As things stand, dialogue between the two countries anytime soon appears unlikely.

Note on data:

All ceasefire violation data is from official Indian sources, Happymon Jacob’s report on ‘Ceasefire Violations in Jammu & Kashmir,’ and from the South Asia Terrorism Portal (SATP; the portal also sources its data from official Indian sources). In cases where there is a discrepancy in the data across the various sources, I refer to official Indian data sources where available. Official Indian data includes data tabled in the Indian parliament and press releases issued by the Ministry of Defense and the Ministry of Home Affairs (Government of India).

Links:

Instead of links, I have a book recommendation for Indialog readers in this edition. I recently finished reading If, Then: How the Simulmatics Corporation Invented the Future by Jill Lepore.

The book traces the story of ‘Simulmatics Corporation’ (‘Simulmatics’ - the company name created by mashing the terms ‘simulation’ and ‘automatic’), a firm established in the 1950s to mine data, target voters and consumers, and shape human behavior. If this sounds like a tech company that you are presently familiar with, that is partly the point of this book.

While ‘Simulmatics Corporation’ died, companies today have been able to do (remarkably well) what Simulmatics set out to do. As the author notes in the concluding chapter, “The invention of the future has a history, decades old, dilapidated. Simulmatics is its cautionary tale, a timeworn fable, a story of yesterday.” [If you want a shorter version, read this article by the author].

One example from the book that stood out to me (and reinforces the author’s argument about links between the past and the present) was a quote from John F. Kennedy in 1960: “When a machine takes the job of ten men, where do those ten men go?” Worries about automation and its impact on the economy persisted then, as they do now with AI.

I dug around the JFK digital archives and found this speech from June 1960 given by then-Senator Kennedy to the American Federation of Labor, Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) in Michigan. The quote (below) stands out because it might as well have been delivered yesterday -

“Today we stand on the threshold of a new industrial revolution — the revolution of automation. This is a revolution bright with the hope of a new prosperity for labor and a new abundance for America — but it is also a revolution which carries the dark menace of industrial dislocation, increasing unemployment, and deepening poverty.” You can read the rest of the speech here.