Geopolitical Risk & India

Summary:

Rising geopolitical tensions have been accompanied by a greater interest in geopolitical advisors.

Can geopolitical risk be measured? Equally crucially, how does this affect India?

Introduction:

In the past three months, Bloomberg and the Economist have written about the demand for, and the accompanying rise of, geopolitical advisors. McKinsey and Goldman Sachs recently established geopolitical risk verticals. Heads of global institutions like Ajay Banga at the World Bank, Jamie Dimon at J.P. Morgan, and António Guterres at the UN, have cautioned against the risks that geopolitical tensions pose to the world.

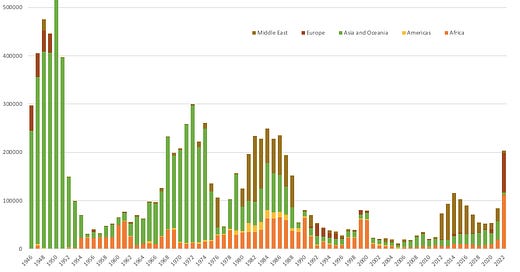

The idea that geopolitical tensions and conflicts can be devastating and destabilizing is not novel. However, the recent phenomenon highlighted above represents a microcosm, albeit an elite-dominated one, of changes and trends that are occurring at the global level (see Fig. 1 on the rise in the number of deaths in state-based conflicts; data from UCDP).

In the past three years, the world witnessed a pandemic that shut down the global economy, at least seven coups in Africa, a border clash between two nuclearized states that continues to simmer, devastating floods in Pakistan with damages in the tens of billions, an invasion initiated by a nuclear-armed state that has drawn in much of the west and has reportedly stalemated, and most recently, a conflict in the Middle East that has the potential to escalate dragging in other actors in the region.

All of this is occurring as the world’s two largest economies and military powers, the United States and China, figure out ways to prevent already hostile ties from further worsening. This forms the backdrop of an international order where global institutions are seen as ineffectual. Middle powers unhappy with the status quo are seeking to reshape parts of the global order to their liking. How does all of this affect India?

Geopolitical Risk & India:

An India that is growing and seeks to occupy a greater role on the world stage will have to contend with crises that emerge across the globe. Commentary on how geopolitical risks might affect India usually touches on accompanying economic consequences. Recent analyses of geopolitical risks focus on how India might benefit from Western countries and companies seeking to limit engagement with China, and concerns within the Indian business community about uncertainties emerging from conflicts.

A challenge here is the unpredictable nature of crises. While issues can appear to be inevitable in hindsight, a Bloomberg report on geopolitical risks encapsulates the daunting nature of the problem. Geopolitical risk, “defies modeling” and consists of “known knowns, such as China’s frustration with US curbs on the export of advanced semiconductor technology; known unknowns, such as where and when the Russian military may use tactical nuclear weapons in Ukraine; and worst of all, unknown knowns” [emphasis added].

For instance, even as the Russia-Ukraine war unfolded, there were few certainties about how the conflict might impact India. More than a year on, some trends are clear. Russia’s invasion resulted in higher fuel and fertilizer prices even as India’s supply chains reportedly faced limited impact “as its huge economy has little reliance on the global market for food.” On the one hand, India saved around $2.7 billion from buying discounted Russian oil, and on the other, there are concerns about Russia’s ability to deliver defense systems that India purchased in 2018. Indian students are affected as the Indian government evacuated around 20,000 students from Ukraine after Russian shelling resulted in the death of a student in the early days of the war. Around 1000 Indians have since returned to Ukraine to continue their studies. These are just a few of the many ways in which the Russia-Ukraine war has impacted India. Given that many other crises are brewing, measuring geopolitical risks is a crucial challenge.

Measuring risk:

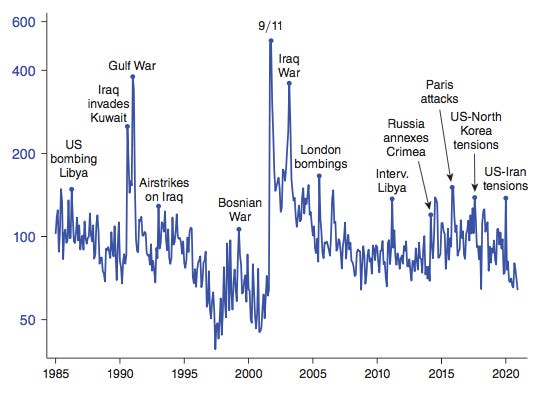

Notwithstanding the difficulties around measuring risk, it is something that must be done given the significant attendant costs. An interesting recent paper sheds light on the measurement of geopolitical risk – ‘GPR’. Caldara and Iacoviello define geopolitical risk as “the threat, realization, and escalation of adverse events associated with wars, terrorism, and any tensions among states and political actors that affect the peaceful course of international relations” and use a news-based approach to study it.

From automated text searches in 10 newspapers (6 from the U.S., 3 from the U.K., and 1 from Canada), the authors construct a recent GPR index (see Fig. 2; image reproduced from Caldara and Iacoviello’s paper).

Their study reveals that “higher geopolitical risk foreshadows lower investment and is associated with higher disaster probability and larger downside risks to GDP growth.” They also use their dataset to create country-specific GPR indices (see Fig. 3 for India’s GPR Index; image from country-specific GPR index).

As per Caldara and Iacoviello’s dataset, in the past fifteen years, the highest GPR emerged following the 26/11 terror attacks in Mumbai, India. Since then, the GPR index briefly spiked around the time of the Pulwama terror attack in Kashmir (in February 2019) and for unspecified reasons in September 2021 and 2022 respectively. Interestingly, India’s GPR index has remained largely stable over the past decade, with the most severe fluctuation in 2008.

Limitations around the dataset and casual attributes should be kept in mind while drawing inferences from the GPR index. However, using news articles is a recognized mechanism to measure and study uncertainty. Writing from an Indian perspective, three officials from the Department of Economic and Policy Research within the Reserve Bank of India (RBI, India’s central bank) recently noted that approaches to measure uncertainty include financial markets data, data on news articles and internet searches, and forecasts (see the article titled ‘Measuring Uncertainty: An Indian Perspective’). One of the ways in which the RBI measures uncertainty is through a Survey of Professional Forecasters (SPF) which has now been running for 16 years.

Forecasting itself is not new. Weather forecasting can be traced back to 650 BC and prediction competitions similarly go back millennia. Macroeconomic forecasting developed as a “product of the Keynesian revolution” in the 1930s and 1940s. However, there are barriers to forecasting when it comes to geopolitical crises. This has mostly to do with limitations around data. While other models of forecasting rest on data that are in parts observable and reliable, forecasting for geopolitical crises can’t make use of similar kinds of data to the same extent.

An intriguing, and relatively recent, phenomenon is crowdsourcing forecasting. Popularized by Dr. Philip Tetlock, forecasting was crowdsourced using a curated team of researchers, dubbed ‘superforecasters’ to stunning effect for a competition organized by the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity (IARPA) housed within the U.S. Government’s Office of the Director of National Intelligence from 2011-2015. The aim of the competition was to “ develop and test tools to provide accurate, timely, and continuous probabilistic forecasts and early warning of global events.” Dr. Tetlock and his team were “at least one-third more accurate than other research teams.” The U.K. government has a similar forecasting platform to “improve its intelligence analysis,” dubbed the ‘Cosmic Bazaar’. More recently, the U.S. government launched ‘INFER’ (INtegrated Forecasting and Estimates of Risk), an “ecosystem of forecasting platforms.”

These strides and new mechanisms in determining geopolitical risk don’t take away from the fact that measuring risk and uncertainty is an extremely arduous task with a number of “unknown unknowns”. This fact collides with the reality of widespread worry about how geopolitical risks may impact people, businesses, and states. Concern around such risks is clear from statements by world leaders and across the global business community. Within India, this concern is similarly voiced by the RBI and business elites.

Measures to navigate geopolitical risks include the creation of frameworks, recommendations on crowdsourcing forecasting through public and private channels, and learning from history to probabilistically determine future scenarios. Each of these methods comes with its own constraints. However, it is clear that there must be some efforts made toward detecting geopolitical faultlines and assessing how crises might play out. Measuring geopolitical risks forms the initial basis for managing crises.

Links:

On Israel-Palestine: There is no dearth of information about the unfolding crisis in the Middle East. I am linking three conversations that I recently learned from.

Listen to the UN Secretary-General talk to CNN’s Fareed Zakaria about “governing Gaza” and the role that other countries can play. Dr. Khalil Shikaki, Director of the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research, spoke to the Carnegie Endowment’s Aaron David Miller. Dr. Shikaki sheds light on a number of aspects, especially public opinion on the ground. Amjad Iraqi, Palestinian policy analyst and writer, speaks with Ezra Klein, covering the history of the conflict and what Hamas’ actions have brought about.

On a related note: This article by Suhasini Haidar in The Hindu sheds light on the Indian government’s response to India’s voting pattern on UN draft resolutions [for an ungated version, see here].

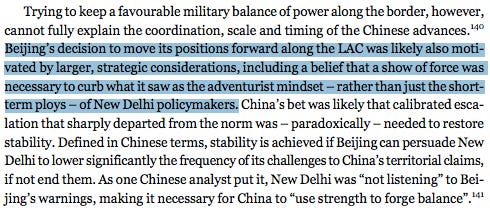

On India-China: The Crisis Group has a new report out on the India-China border clash. While much ink has been spilled on the standoff, this report provides context to the border dispute and crucially, consists of interviews with a number of Indian and Chinese officials.

On climate change: This Polycrisis piece on ‘Global Burning’ is one of the most succinct pieces I have come across on the state of climate change and the evolution in policy approaches to mitigate it.

If you are interested in “the political economy of climate change and global North/South dynamics” consider subscribing to ‘The Polycrisis’ newsletter (published by Phenomenal World).