Democratizing Indian Foreign Policy

Summary:

An interesting aspect (and aim) of India’s G20 presidency was to ‘democratize’ foreign policy.

While foreign policy is generally considered to be an elite issue, survey data reveals interesting insights about how Indians view foreign policy issues.

Democratizing foreign policy raises questions on how policy might be impacted, and systematic studies of this phenomenon require greater survey data.

Introduction:

An interesting aspect (and aim) of India’s G20 presidency was to ‘democratize’ foreign policy. This was carried out by organizing around 220 meetings across 60 cities which reportedly saw more than 100,000 people participate in G20-related events. In an interview, Dr. Jaishankar, India’s External Affairs Minister, stated that past gatherings were done in a “bureaucratic” way and the idea with the 2023 G20 was to see if it could be done differently and “take it out to the rest of the country” [3:10-4:06].

On September 6, 2023, the Foreign Minister noted that “the extensive participation of people, or Jan Bhagidari from across the nation” has added to India’s G20 presidency. On September 7, 2023, the Prime Minister asserted that the G20 “is not merely a high-level diplomatic endeavor” – rather “it has become a people-driven movement.”

Alongside the stated aims of the ‘Jan Bhagidari’ initiative, one can argue that such an initiative was undertaken with an eye to domestic politics. Ananth Krishnan and Suhasini Haidar highlighted how a diplomatic event was transformed into a political spectacle. Reactions from visiting foreign delegations varied. Some visitors asked if G20 posters featuring the Prime Minister every few dozen meters were “normal in Indian culture.” A U.S. diplomat stated that he wished the “United States had had the foresight to create this kind of buzz during its own [G20] chairmanship.”

As a retired Indian diplomat noted, “India is trying to blur the line between foreign affairs and domestic politics, and the G20 is the most important forum to achieve that. The government realizes that.” Journalists highlight the pride Indians perceive over the “rise in India’s influence in the world.” However, there is a lack of systematic study of the effects of democratizing foreign policy.

I note that the ‘democratization’ of foreign policy is an interesting aspect because conventional scholarly views note that foreign policy is usually an elite concern. Academic works on political psychology and international relations see this phenomenon as a “domain of elite decision-making, rather than mass political behavior.” One way the democratization of foreign policy can be studied is by looking at public opinion.

Foreign policy & public opinion in India:

One of the early efforts at tracking Indian public opinion was undertaken by the Indian Institute of Public Opinion (IIOPO). Conducted in the 1950s, these surveys focused on ‘elites’ (respondents were university-educated people from Chennai, Delhi, Kolkata, and Mumbai). Aidan Milliff, Paul Staniland, and Vipin Narang analyzed this survey data in a 2019 working paper.

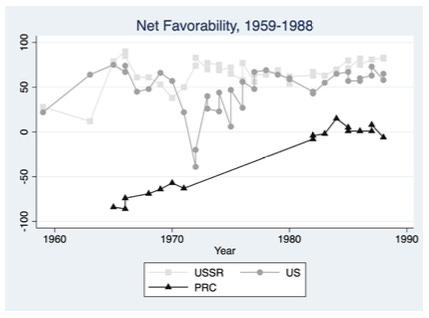

A notable data point from their paper includes observations around the net favorability of the ‘great powers’ – China, the Soviet Union, and the United States, i.e. how Indians think about these states (see Fig. 1).

Given India’s ties with each of these nations, the favorability data above might be commonsensical. However, favorable views towards the United States (almost on par with the Soviet Union) arguably cut against conventional ideas about the state of Indo-U.S. ties. The authors note that “the urban public was fairly pro-US in the 1960s and 1980s, making the 1990s rapprochement perhaps less of a surprise than some have framed it.” It is imperative to note that this data is based on surveys with a small part of India’s populace and is not truly representative.

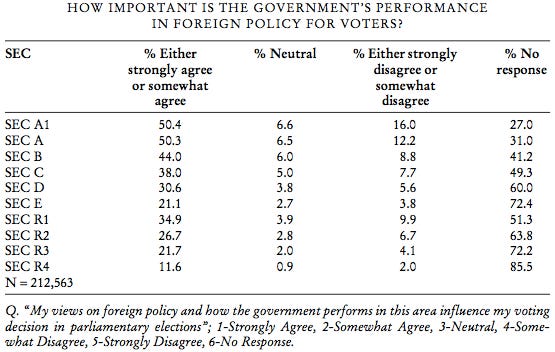

The idea that foreign policy is largely an elite issue and not a ‘mass’ concern, can be gleaned from other sources. For instance, in a 1971 post-poll election survey carried out by Lokniti-CSDS (Centre for the Study of Developing Societies), the most salient issues were broadly economic. For instance, when asked what are “some of the major problems facing” India (see Q. no. 53(1) in the survey), the responses were:

As this survey data shows, foreign policy doesn’t rank high among the issues that concern most survey respondents. While the number of foreign policy-related questions in this 1971 survey is few, each response highlights the limited salience of the subject.

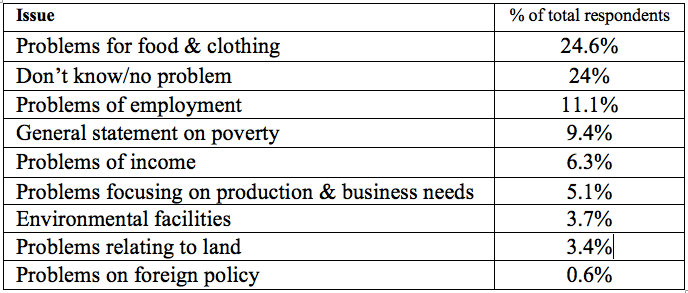

Another major survey that highlights a similar finding is the one conducted by Devesh Kapur in 2005-06. This nationally-representative survey of foreign policy attitudes covered 212,563 households. One of the key results from the study was the link between “non-responsiveness to questions on foreign policy and socio-economic status” (see Fig. 2).

The most elite socio-economic group in the survey (SEC A1, see Fig. 2) had a non-response rate (to foreign policy questions) of 28.7%, whereas the lowest socio-economic group (SEC R4) had a rate of 82.2%. This relationship between socio-economic status and responsiveness plays out in a similar way when questions about the importance of foreign policy are put forth.

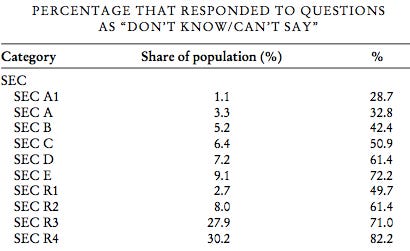

The author notes that “when asked if their views on foreign policy and how the government performs in this area influenced their voting decision in parliamentary elections, about half of respondents in the SEC A category either strongly or somewhat agreed with the proposition, whereas the fraction was just above a tenth for SEC R4” (see Fig. 3).

Results from this study conform with conventional views on public opinion and foreign policy – the idea that the masses “have little interest in foreign policy issues.” The lack of interest or knowledge, however, should not preclude one from having an opinion.

Recent studies:

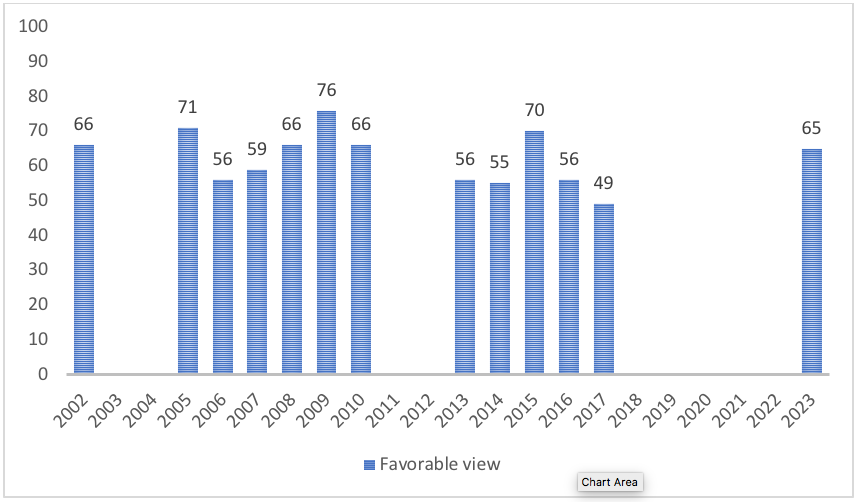

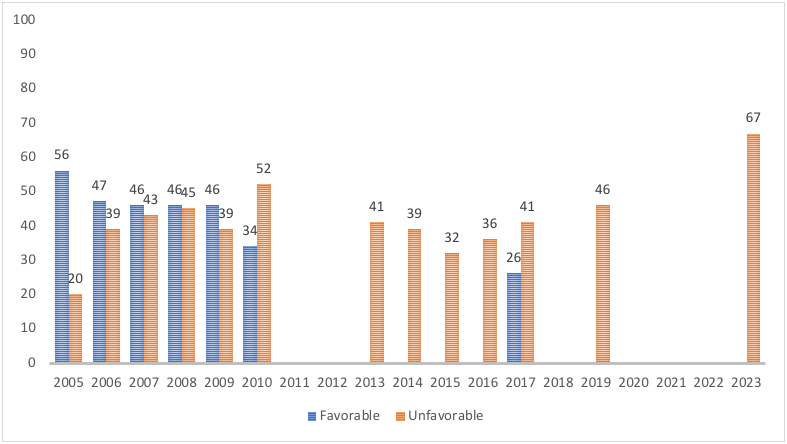

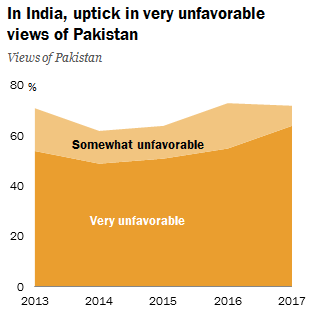

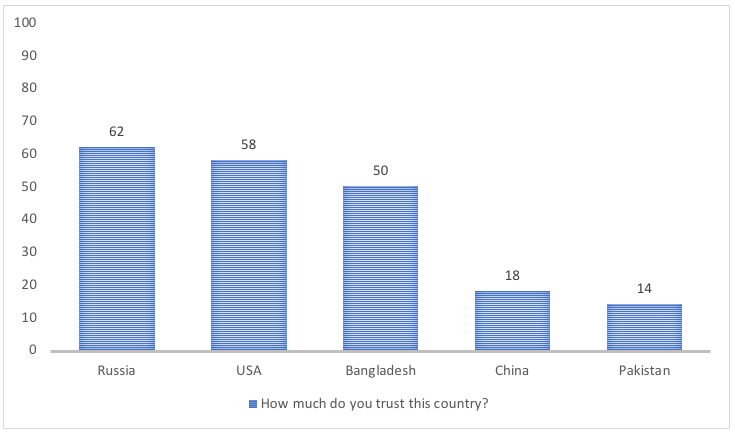

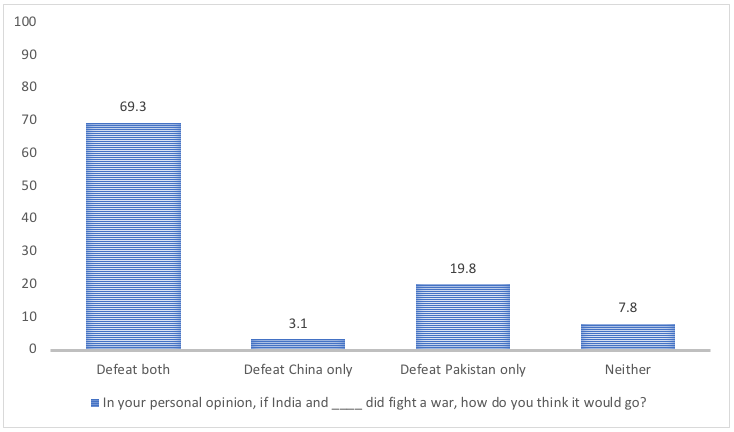

To gauge public opinion on foreign policy, regular surveys and studies are necessary. However, as studies on this subject note, one of the key constraints is the limited availability of data. A notable exception is the work undertaken by Pew. In 2002, it launched the ‘Global Attitudes’ report surveying 44 countries’ publics (including Indians) to understand public views on their respective lives, countries, the world, and perceptions about the United States. The entire report, and especially the sections on India, is worth going through to understand what perceptions were like then. On foreign policy matters, three things have been largely consistent among Indians: i) positive views of the U.S. (see Fig. 4) ii) negative views of China (see Fig. 5), and iii) negative views of Pakistan (see Fig. 6).

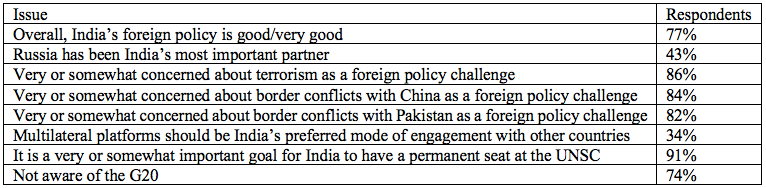

In recent years, there has been a spate of surveys that throw light on public opinion on various Indian foreign policy issues. Some interesting results from three different surveys (all released in 2022) are shared below (see Table 2, Fig. 7 & 8).

These three different surveys touch on various aspects of public opinion on foreign policy matters. Needless to say, survey sample sizes and methodologies vary, and I have highlighted only some of the survey findings.

Why does public opinion on foreign policy matter?

While public opinion data on foreign policy issues reveals interesting insights, the question arises: why does public opinion matter? At one level, public opinion matters in democratic systems because there is an assumption of a connection between what the public thinks and the policies pursued. Although this connection may be “weak and tenuous,” as one scholar notes, democratic theories often focus on the importance of responsiveness to the public in democratic governance.

The degree to which this is a reliable assumption can be, and is, debated. For example, in 2020, Neelanjan Sircar developed a “model of the politics of vishwas (trust/belief)” to shed light on the 2019 national election results. He argues that this is a “form of personal politics in which voters prefer to centralize political power in a strong leader, and trust the leader to make good decisions for the policy – in contrast to the standard models of democratic accountability and issue-based politics” [emphasis added].

While there will be debates about the extent to which public opinion matters for foreign policy in a broader context, an interesting potential outcome of the G20 could be to further democratize foreign policy. Understanding what this means requires regular surveys that break down public opinion data across regions and various socioeconomic brackets. Crucially, it also raises interesting questions on what ‘democratizing’ foreign policy entails and how it might affect policy in the future.

Links:

On climate change/solar energy: A recent report from Ember, an energy think tank, highlights the crucial role solar and wind will play in a fast-evolving energy landscape in India. The authors note that “solar and wind are likely to drive India’s electricity generation growth from FY 2022-2032, in contrast to the previously coal-dominated decade.”

On industrial policy: Suyash Rai reviews the state of the ‘Make in India’ policy by looking at the share of manufacturing in the gross value added (GVA), the gross fixed capital formation in manufacturing as a percentage of the GDP, employment numbers in the manufacturing sector, foreign direct investment (FDI) into India, and the value of exports of manufactured goods as a percentage of India’s GDP. He notes that “we can see the success of Make in India everywhere except in the national accounts statistics, employment figures, foreign investment figures, and trade flows.”

On artificial intelligence: AI is seemingly everywhere. For those who may not know enough about AI but are curious (like yours truly), this OECD report on ‘AI and its use in the public sector’ covers all the bases including definitions, AI approaches, emerging government practices, and an interesting set of case studies (focused on the west).