Policy Playbook #3: Trump 2.0, India, and the subcontinent with Daniel Markey and Elizabeth Threlkeld

An overview of U.S. ties with South Asian states during Pres. Trump's first administration, analyses of Trump 2.0, and insights on India-U.S. ties from two leading American scholars and policymakers.

Note: I authored the Introduction section (below) in the week of January 13 in an attempt to anticipate President Trump’s second presidency. As events from the last few weeks demonstrate, the volatility that could emerge from the U.S. was arguably understated before Trump’s return.

Sample this recent Financial Times report on the ‘72 hours of trade chaos’ unleashed by the Trump administration,

“On Monday afternoon, Donald Trump was holding court in the Oval Office, enjoying a moment of calm after days of turmoil in which he had brought Canada and Mexico to the brink of a trade war. Over the previous dizzying 72 hours, the US president had unveiled 25 per cent tariffs on imports from his biggest trading partners, triggering turmoil in the markets, howls of protest from business groups and new doubts about the reliability of the US among its allies. Alongside this was a 10 per cent levy on Chinese imports. Hours before the measures were due to take effect, Ottawa and Mexico City were given a month-long reprieve; Beijing was not… On Sunday and Monday, Canadian and Mexican diplomats and finance ministers rushed to hold calls with their US counterparts. Meanwhile, markets started to show signs of strain. US equity futures plunged ahead of the market opening in New York on Monday… The temporary agreements with Canada and Mexico have a very short lifespan, and Trump could demand new concessions ahead of the March deadline that may be harder to satisfy. Meanwhile, tensions with Beijing have been increasing since the 10 per cent tariffs on Chinese imports took effect on Tuesday, triggering immediate retaliatory measures against US exports to the Asian nation.” [emphasis added]

It is tough to forecast how state relations will pan out under such circumstances. That being said, an attempt has to be made. The introduction section takes a brief look at Trump’s first presidency to provide some context to the following conversation. The second section contains the interview with Daniel Markey and Elizabeth Threlkeld where we cover quite a bit of ground including the United States’ ties with India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan, and the interviewees’ analyses of Trump 1.0 and predictions for Trump 2.0. The concluding third section has a comprehensive bibliography.

If you find any value in this interview, I urge you to share this newsletter with your friends and colleagues.

I. Introduction:

On January 20, 2025, Donald J. Trump returned to the White House as the 47th President of the United States. Based on President Trump’s first term, the United States is expected to become “less predictable, more chaotic, colder to allies and stronger to some strongmen, and much more transactional in picking friends globally than before.”

Writing on Trump’s return to office, Michael Froman, the president of the Council on Foreign Relations notes,

“Trump will re-enter office in ten days with significant assets at his disposal, at home and abroad. He has majorities in both houses of Congress, and he is appointing a team committed to implementing his vision faithfully. Leaders across the world are all asking the same question: What do I need to do to cut a deal with him?” [emphasis added]

Transactionality appears to be the keyword in the United States’ dealings with other countries under Trump. Foreign Policy’s Ravi Agrawal writes,

“Pundits reflexively see Trump’s nakedly transactional nature as an attribute that might terrify other global stakeholders. The reality is more complicated. States that have come to rely on U.S.-backed alliances will certainly need to recalibrate. Global markets will experience turbulence. But countries and companies will also sniff out opportunities. The ones with the means to do so will look to exploit the president-elect’s tendency to prioritize his self-interest.”

Leaders across the world, including South Asia, will watch how Trump 2.0 unfolds. Some nations appear to be better placed than others in dealing with a Trump-helmed White House. India’s external affairs minister, Dr. S. Jaishankar, said that India isn’t one of the countries that is “nervous about the U.S.” following the November 2024 election results. This may be true in some sense, as India-U.S. security and energy ties soared under President Trump during his first term [see Fig. 1].

However, there remain areas of concern in this bilateral relationship. Trade and immigration are likely to be the two most contentious issues. During Trump’s first term, “most of the tensions” in the relationship “came from the two countries’ similar approaches on trade” as CSIS’ Rick Rossow notes. He further argued that,

“Both the United States and India continue to have large trade deficits with the world. The Modi government’s initial protectionist policy steps to support “Make in India” conflicted with the Trump administration’s manufacturing and export plans. The two nations entered an intense trade war which saw the United States revoke India’s trade privileges under the Generalized System of Preferences program. India put retaliatory duties against a range of American products due to the Trump administration’s tariff increases on steel and aluminum. The efforts to negotiate a modest package of reforms to address some of these pain points on trade fell apart late in the Trump administration’s first term.” [emphasis added]

Trump spoke positively of Prime Minister Modi and their relationship on the campaign trail. However, he also noted that India was a “very big abuser” of trade ties with the United States, and reiterated that India imposes heavy tariffs on imports. While the past is not necessarily precedent when it comes to Trump, he wasted little time in expressing his intent to use tariffs as a stick once he was re-elected.

C. Raja Mohan reminds us that “India has had a bitter taste of Trump’s relentless focus on market access and trade deficits in the first term.” Now that the United States is India’s “most important commercial partner,” Mohan argues that “Delhi will have to do more than tinkering with its policies to deal with Trump’s emphasis on fair trade.” [emphasis added]

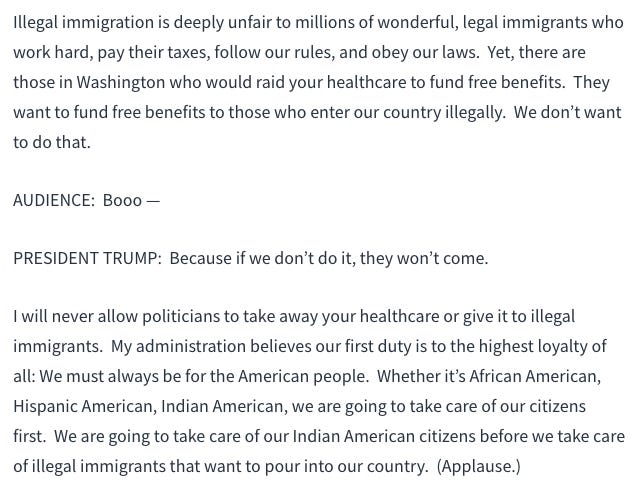

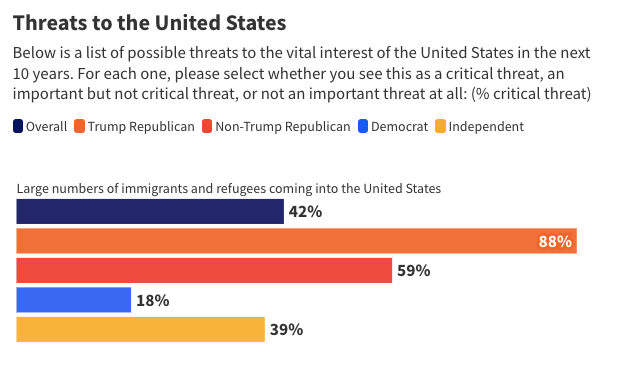

We recently also got a taste of how the debate on immigration - another potential sticking point in the India-U.S. relationship - might play out within the Republican party and base with the controversy around the appointment of Chennai-born Sriram Krishnan as a senior policy advisor for AI in the Trump administration. Krishnan’s appointment sparked a furious debate among Republicans that pitted Trump’s “advisors from the tech world against Republicans who want a harder line on all forms of immigration.” Trump sided with Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy in the debate, telling a media publication that he “always liked” H-1B visas [also see Figure 2].

While there has been no change in policy yet, Indians, the main beneficiaries of the H1-B visa [per official U.S. government data 72% of the 3,80,000 H-1B visas issued in 2023 were granted to Indians], are already being impacted. A recent Indian media report highlighted how Indians looking to move to the U.S. and Indians in the States awaiting H1-B visa renewals are facing delays as firms wait for greater clarity on the subject from the Trump administration. Immigration, a galvanizing issue for the Republican party and base, remains far from resolved, and it’d be a safe bet to expect greater turbulence in the months and years ahead.1

While Trump 1.0 was a ‘mixed bag’ for India-U.S. ties, other nations in the subcontinent like Bhutan, Maldives, and Nepal might be more worried about “a lack of attention from the new [Trump] administration” rather than any wariness about U.S. actions per Suhasini Haidar. Writing in 2019, Alyssa Ayres noted that South Asia was one region “where Trump’s declared policies have hewed in great part to those of prior administrations, especially in the defense and strategic realms.”

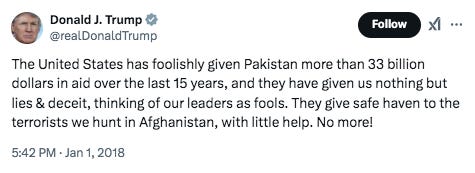

When Trump presented his administration’s South Asia policy in 2017, he stated that “America will continue its support for the Afghan government and the Afghan military as they confront the Taliban in the field.” He also noted the support Pakistan provided for U.S. operations in Afghanistan before calling out the former for harboring “militants and terrorists who target U.S. servicemembers and officials” and providing “safe havens for terrorist organizations, the Taliban, and other groups that pose a threat to the region and beyond.” Trump’s speech was termed “perhaps the strongest public criticism by a U.S. president of Pakistan’s policy in that war.”

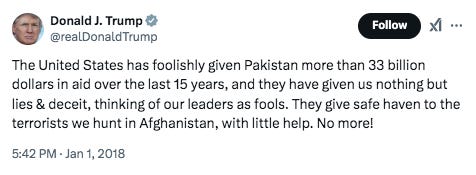

Following this 2017 speech, Trump continued to criticize Pakistan [see Fig. 4]. Trump’s tweets calling out Pakistan “gave full display to the frustration in the executive branch” which were followed up with strong actions including the suspension of $1.66 billion in security assistance.2 Perhaps the only high point in the Pakistan-U.S. relationship was President Trump’s meeting with then-Prime Minister Imran Khan in a bid to mend ties.3 However, as Touqir Hussain argues Trump sought Imran Khan’s help in talking to the Taliban and to get U.S. forces out of Afghanistan – “once the deal with the Taliban was done, Trump turned his back on Pakistan, leaving no imprint on the relationship.”

One of the primary concerns for those in Pakistan is Trump’s indifference towards the former.4 As Hussain writes,

“Trump notices only issues of high public interest, which have political traction. The present state of US-Pakistan relations is not one of them, neither are its domestic dynamics. Trump will most likely continue with the Joe Biden policy of low-intensity engagement with Islamabad, marked neither by significant aid levels nor by sanctions, the two extremes between which the relationship oscillated for much of its history.”

In 2019, U.S.-Pakistan ties fared better. This was primarily because the United States needed the latter’s assistance in ensuring a withdrawal from Afghanistan, as Hussain pointed out in his assessment of Pakistan-U.S. ties under Trump 2.0.

During Trump’s first term, Afghanistan occupied much of the administration’s energies as the President wanted to get U.S. troops out. When Trump outlined his 2017 South Asia policy, he highlighted how the U.S. wouldn’t withdraw hastily noting that

“in 2011, America hastily and mistakenly withdrew from Iraq. As a result, our hard-won gains slipped back into the hands of terrorist enemies… We cannot repeat in Afghanistan the mistakes our leaders made in Iraq.”

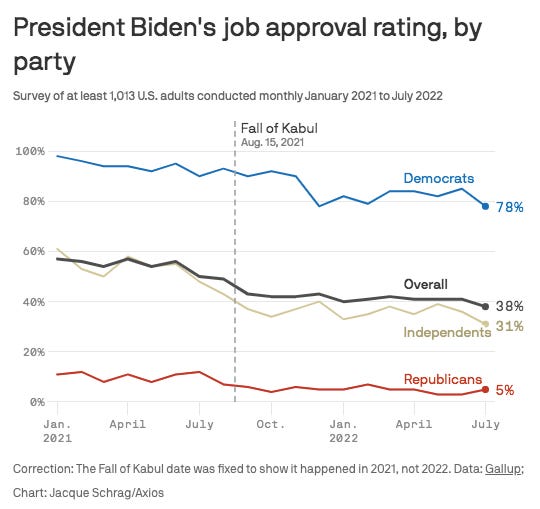

By 2019 it was clear that the Afghan government had been “completely relegated to the sidelines” as the United States government dealt with the Taliban. This was primarily because the Trump administration needed a “face-saving exit strategy” in Rani Mullen’s assessment. Safe to say, it was President Trump’s administration that buttressed the Taliban’s legitimacy, leading to an eventual, badly planned (to say the least) U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan under President Biden (Joe Biden’s approval ratings dipped below 50 percent for the first time in the wake of the chaotic U.S. withdrawal and didn’t really recover after that as Ezra Klein has pointed out multiple times; see Fig. 5).

Following Trump’s re-election in 2024, Zalmay Khalilzad, Trump’s point person on Afghanistan in the first term, called for the revival of the Doha Agreement, with the Taliban responding to Trump’s return with “cautious optimism.” How the Trump administration will respond to developments in Afghanistan since he departed office is unknown, but it is safe to say that Afghanistan isn’t on the priority list. According to one scholar, when it comes to Taliban-ruled Afghanistan, Trump is likely to “favor pragmatic deals over costly confrontations and military entanglements in Afghanistan and elsewhere.”

With Trump’s return to the White House, I interviewed two American scholars to understand how the United States’ relationship with South Asian countries might play out. There is greater emphasis on India-U.S. ties in this interview.

Daniel Markey is a Senior Advisor for the South Asia program at the United States Institute of Peace and a Senior Fellow at the Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) Foreign Policy Institute. Before this, he was a senior research professor in international relations at SAIS, a senior fellow for India, Pakistan, and South Asia at the Council on Foreign Relations, and between 2003 and 2007, a member of the U.S. State Department’s Policy Planning Staff. Dr. Markey has two decades of academic, think tank and government experience focused on international relations and U.S. policy in Asia, with a particular focus on South Asia and China’s evolving role in the region. He is the author of China’s Western Horizon: Beijing and the New Geopolitics of Eurasia (2020) and No Exit from Pakistan: America’s Tortured Relationship with Islamabad (2013).

Elizabeth Threlkeld is a Senior Fellow and Director of the South Asia program at the Stimson Center. She has been with Stimson since 2018 and previously served as the Program’s Deputy Director. Her research interests include nuclear competition in Southern Asia, regional security dynamics, and geopolitics in the Indo-Pacific. Before joining Stimson, she served as a Foreign Service Officer with the U.S. Department of State in Islamabad and Peshawar, Pakistan, and Monterrey, Mexico. She is the recipient of a Department of State Superior Honor Award and the Matilda W. Sinclaire Language Award.

Dr. Markey and Ms. Threlkeld are experts on the United States’ engagements with South Asia, have substantive policy experience having served in the U.S. government, and continue to write thoughtful, incisive pieces on this subject. This interview was conducted on January 16, 2025, and is (lightly) edited for clarity and brevity. Parts of the text (throughout the edition) are in bold for emphasis. I have included links and footnotes to provide context to some of the points raised by Dr. Markey and Ms. Threlkeld. Views expressed are personal and do not represent their respective institutions’s views.

This is the third edition of the Policy Playbook: a series where I will speak with experts, policy-makers, bureaucrats, and others to delve deeper into policy issues that deserve nuance and greater scrutiny.

The first edition contained an interview with Mr. Ajay Srivastava on India-China trade ties [if you read that excellent Rest of World piece on how Chinese workers are being stopped from working in India, I highly recommend this interview with Mr. Srivastava - as a former Indian Trade Services officer, he understands the intricacies of India’s trade relationship very well and is blunt with his assessment of India’s strengths and limitations]. For the second edition, I interviewed Rohan Mukherjee to understand India’s history and relationship with the international order and the UN. Dr. Mukherjee is an expert on the subject and the author of the award-winning Ascending Order: Rising Powers and the Politics of Status in International Institutions and has published works in academic journals such as International Affairs, Global Studies Quarterly, and India Review, among others.

On to the interview –

II. Policy Playbook #3: Trump 2.0 and South Asia with Daniel Markey & Elizabeth Threlkeld

India-U.S. —

Shreyas Shende [SS]: Dan, what was your assessment of the India-U.S. relationship during Trump's first term?

Dan Markey [DM]: Overall, there was a significant amount of progress in the U.S.-India relationship over those four years in a number of different ways. I can break it down a little bit. Politically, we saw an interesting convergence of the Modi-Trump relationship. A certain type of shared politics. One need only remember the ‘Howdy Modi’ event in Houston to get a sense of how they seem to relate fairly effectively to one another, and in some ways to have a certain similarity of style [see Fig. 6]. I wouldn't make too much of that, but there was a convergence there.

Strategically, we can get into this in some greater length, but the Trump administration was a transitional period into a global geopolitical competition with China. There was a recognition of where different players on the world stage fit into that [competition] including India. It is important to recall that the United States was still at war in Afghanistan. That was still a transitional phase out of the post-9/11 era into an era of competition with China. The Trump administration, many members of it, including the President, were pushing that full speed ahead, and India was seen, and had been seen to some degree by the Obama administration before, as an important piece of that geopolitical competition with China. Trump administration officials seized on that notion and pushed it forward. So, for instance, when India identified the Belt and Road Initiative as problematic from its perspective5… the Trump administration was noteworthy for picking that up and picking up many of India's themes and criticising the BRI along similar lines, and that was a signal of an attempt at convergence there.6 Also in the strategic or defence realm, you saw full speed ahead on the foundational defense agreements between India and the U.S. that were necessary to push cooperation forward in those areas, defense and intelligence.7 The one slightly divergent area is the economic one where I think you saw particularly on trade, but also on immigration issues, irritants in the relationship. Now I think it could have been a lot worse. These were not devastating to the relationship. As I said overall, it was a positive, progressive period for the relationship, but incompatibilities in terms of protectionism on both sides also get in the way. U.S. politics with respect to immigration also stymied some of what India would like to see in terms of a freer flow of labor into and out of the United States. So that's my general characterization. There's lots more that could be said, but I think those are the main contours.

SS: Elizabeth, do you want to add to what Dan said?

Elizabeth Threlkeld [ET]: Yeah, I agree with all of that. Just in terms of external factors that really played a role. Of course the Trump Administration was in office for the June 2020 LAC standoff, where we really saw China-India tensions come to the fore in a way that had been somewhat latent previously. I think we can't underestimate the impact that China's own actions had in helping the Trump administration really accelerate this cooperation [between the United States and India] that had been building as Dan just laid out. And you hear folks who were in the Trump administration talk about how closely they worked with India in response to that incident, how meaningful it was to the relationship. Just provision of cold weather gear.8 These kind of tactical signs of support, and I think that to an extent became a bit of a litmus test for what the U.S would be able to do. How it would be able to support India, and to an extent also following India's lead in not being too forward-leaning publicly.9 Not taking the bait and pushing too far beyond what the Indian government was comfortable with in terms of public messaging. Obviously that [India-China border] crisis then endured for the next four years and kind of set up the Biden administration for what it was able to pick up. That external factor, I think, also played a pretty significant role in the developments that we saw under the Trump administration.

Pakistan-U.S. ties —

SS: Elizabeth, could you speak about the state of Pakistan-U.S. ties in Trump’s first term?

ET: As Dan mentioned, it's important to go back in time and reflect on how central Afghanistan was to regional conversations. President Trump outlined his strategy for the region in a 2017 speech, and he spoke about Pakistan almost exclusively through the lens of Afghanistan. This was a time when you saw a kind of shifting approach over the course of the Trump administration, when first it was to take a hard line to try to make gains on the battlefield [in Afghanistan], and shifted pretty quickly to more of a deal making approach. In different ways, Pakistan was central to those efforts and so when we think about the [U.S.-Pakistan] bilateral relationship, I think it's really important to keep that context in mind. It saw some ups and downs, most notably the first tweet of 2018 from President Trump, when he called out Pakistan's duplicity in supporting the Taliban in the context of Afghanistan, and cut off security assistance to Pakistan [see Figure 7]. That obviously was a pretty significant moment.. that was then relaxed over the course of the next several years. I think it speaks to the extent to which the security relationship that the U.S. had built with Pakistan over the course of the nearly 20 years in the war saw some pretty dramatic changes under the first Trump administration, in line with the dramatic changes that we saw in Afghanistan.

Of course, Pakistan played a key role in facilitating the talks that ultimately concluded with the 2020 deal in Doha with the Taliban.10 That was one piece of the puzzle. I think another two things to focus on here. One is that the personal relationship between President Trump and then Prime Minister Imran Khan. Imran Khan made a July 2019 visit to Washington where he spoke at USIP [the United States Institute of Peace].11 The two of them [Trump and Khan] reportedly hit it off and had a positive relationship [see Figure 8]. That could come back up in various ways. It certainly has been a topic of conversation among Imran Khan's supporters in Pakistan.

One other thing I'll mention here is the 2019 Balakot crisis. So this started with an attack on an Indian security convoy that killed around 40 service members claimed by a Pakistan-based group. We saw for the first time the U.S. step away from the traditional role that it had played as a third-party crisis manager with John Bolton expressing what was at least interpreted as a green light for an Indian response to that attack.12 I think that is a notable moment in terms of the ways that the shifting regional geopolitics have intersected with strategic stability, crisis stability issues, with the attempts that the U.S. has historically made to keep a lid on escalation risk in the region. Fortunately through some diplomacy, but also quite a bit of luck, that crisis did not escalate, but we did see a couple of rounds that were quite scary, and so going forward, I think that's always a risk to keep in mind.13 There’s just a question mark of how the incoming administration might approach that going forward.

SS: Dan, would you like to add anything to that?

DM: Elizabeth covered all the important points. I would just reinforce the centrality of Afghanistan and the continuing war in Afghanistan for U.S. policy on Pakistan. We really were seeing Pakistan as an extension of that set of problems, despite, as Elizabeth pointed out, some good relations between Trump and Imran Khan. This was the end of an era in terms of a U.S. aid relationship with Pakistan that might have conceivably been rekindled during this period. In other words, there were tough decisions made during the Trump administration: not to go back into a military aid relationship, not to see Pakistan as a necessary or indispensable partner in the region, in the way that, at times, the Obama and Bush administrations had. It's been interesting because the Biden administration didn't reverse those decisions either.14 So it had a lasting consequence, not just for the Trump administration, but it was picked up by the next administration, and continues to be the shape U.S. policy. It was an important time.

Trump & the subcontinent —

SS: This is helpful. I want to reiterate just how tense the 2019 Balakot crisis period was, and as Elizabeth correctly noted, there was quite a bit of luck involved in ensuring the crisis didn’t further escalate.15 The rest of the conversation is going to focus quite a bit on India, and on Afghanistan and Pakistan as well. I also want to touch on other countries in the neighborhood, and get a sense from both of you on the United States’ relationship with other countries in the subcontinent during Trump’s first term. Dan if you want to go first…

DM: Sure. Well, we've already mentioned Afghanistan. If we're trying to be honest about where the mind space of this Trump administration was at that time… You know it's not Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, or Nepal. It’s not even Myanmar. It is definitely Afghanistan and negotiations associated with trying to end the war there. As Elizabeth pointed out, this started with a ramp up of military force, relaxed rules of engagement, and so on. This was the nature of a lot of the conversation. The question was how best to bring to an end nearly 20 years of a war, to still address counterterrorism challenges, and to do so in ways that fit with the broader Trump administration approach, which was a more forceful one in the region. With respect to the other countries in the region, the Trump era marked the beginning stages of a reaction to China’s ‘Belt and Road Initiative’ and all of the things that went with that. One of the strategies that really got some attention at the time was an emphasis on debt-trap diplomacy. This continued into the Biden administration. The Trump administration started questioning, not just China's motives, but China's tactics and the consequences or implications for smaller countries in the region of accepting Chinese aid in development projects. US officials started suggesting that Chinese aid was a poison pill and that the best answer to Chinese assistance and investment was ‘no.’ This went hand in hand with a broader project of expanding U.S. geopolitical competition with China. That competition extended into infrastructure and investments of the hard kind, like roads, but also things like telecommunications, Huawei and so on.16 So the Trump administration's game plan for responding to [China’s moves] influenced US relations across the region. It had mixed effects. Not everybody [in the subcontinent] took the ‘just say no’ line to heart as we have certainly discussed it many times since then. You can't beat something with nothing. If the Chinese were offering cheap 5G, or other telecommunications support, and infrastructure, then the US would have to offer attractive alternatives. The Trump administration initially had only tentative or initial answers to that, but it set the stage for framing the U.S. relationship with these other countries in the context of the U.S.-China relationship in ways that we really hadn't seen before. So that was a sea change.

SS: Elizabeth, what is your sense of the United States’ relationship with other countries in the region during Trump’s first presidency?

ET: I think Dan's exactly right. The two significant broader trends certainly were the Afghanistan lens, and then the emerging geopolitical competition with China. Specifically, we saw the Hambantota port issue in Sri Lanka gain prominence during this time. You saw U.S. and the Maldives sign a defense agreement in 2020, which was, at least in my interpretation, done with an eye towards China. It also important to reflect on the policy approaches that were more reactive to regional events. August 2017 saw the outbreak of violence in Rakhine state and the Rohingya refugee crisis into Bangladesh. The U.S. provided humanitarian aid support to the Bangladeshi government. Then Nepal saw the Nepalese government sign the MCC [Millenium Challenge Corporation] compact in 2017, though obviously there were some bumps in the road there. Across the region, I would say to the extent that there was a regional focus, the primary lens in smaller South Asian states was this evolving U.S. competition with China and for those that have more equities in Afghanistan that came to the floor. Pakistan was kind of an interesting mix of those two [trends] where we first saw the Trump administration take a very hard line against CPEC in particular, which was an interesting evolution from the Obama Administration's early approach, so that really hardened under the Trump administration.

Trump 2.0 & India —

SS: Dan, while reviewing President Biden’s ‘Indo-Pacific Strategy,’ you wrote [in a piece from 2024] that his administration devoted a “stunning level of time and energy” to support “a strong India as a partner” noting that “process-wise, the past two years [2021-23] saw the India-U.S. relationship firing on all cylinders” pointing out strides in the defense relationship. You also highlighted challenges in the relationship including allegations of India’s attempt to assassinate a U.S. citizen on U.S. soil and concerns about democratic backsliding (you’d also raised the latter issue in your Foreign Affairs article, ‘India as It Is’). How do you see the India-U.S. relationship changing in Trump’s second administration, and where might we see a) a flouring of the relationship, and b) challenges?

DM: Great question. So one thing to observe would be that it's not always the case that personality defines policy. Or that the individual personnel selected for positions will control outcomes. But it is a good starting point, particularly when we don't have much else to go on in the new Trump administration. We can see that some of the key picks on his national security team are very enthusiastic supporters of a closer relationship with India. I'll start with the National Security Advisor. Mike Waltz, India caucus leader as a member of the House of Representatives, someone who very clearly and forcefully has spoken of the need for the United States to continue, and if anything, push faster and harder to build out closer ties with India [see Figure 9].17

When I wrote earlier that we have seen an extraordinary amount of attention and energy by the Biden administration placed on its relationship with India, it is conceivable that we'll see something similar by this Trump administration. The problem is the first Trump administration was not known for being process oriented. The Biden administration has been stunningly disciplined in its process, particularly the White House, and in its effort to push the U.S.-India relationship. So style could be a big difference.

Sometimes a very different style, a personalized style, one that maybe will bounce around less systematically in its approach to policies, may or may not play to India's advantage, or to the advantage of the U.S.-India relationship. I don't know how that will look. It could go either way, but it will be different. So there will be continuities in terms of, impulses and motivations in the relationship, but changes in terms of processes, procedures, and personalities certainly. In terms of substance, the Biden administration has clearly placed critical and emerging technologies, and this NSA to NSA partnership on iCET [U.S.-India Initiative on Critical and Emerging Technologies] at the center of what they see as the future of the U.S.-India partnership. These activities were at the center of the Biden team’s logic for why the United States should see India as an important strategic partner. I think the Trump administration can pick that up and run with it as well. The challenge there is only to what extent the Trump Administration, with its avowed ‘America First’ program will see partnership with India as something that it is doing that serves American purposes. In other words, [for] the United States, under a Trump administration, primacy is central. If India will help with American primacy, then full speed ahead. But if anything begins to look like doing more for India, just because it's good for India, but maybe not immediately good for the United States, then I think you'll begin to see different kinds of questions raised in Washington. Those are some initial thoughts.

A couple of other things… You mentioned the assassination plot against a U.S. citizen and some of the irritants in the U.S.-India relationship that one included.18 My understanding is that National Security Advisor Sullivan, during his trip to India, may have tried to smooth some of that over and kind of end that as an area of further concern between the United States and India. We’ll see if that holds. I think that is an area where the Trump administration, like the Biden administration, will be eager to sweep it under the carpet and get back to business, and maybe even more so. We'll see how that goes. There are certain types of irritants, broader questions of democracy and human rights. Again, the Trump Administration will say things about this, but largely in other contexts. So Venezuela, Iran maybe, certainly China and the Uyghurs, and protections for Christians internationally. In the first term at least, the Trump administration was less critical of Prime Minister Modi and of India, and was eager to steer clear of those types of issues, so we could imagine that happening as well. I would just conclude by saying, Marco Rubio,19 another important player in in this new administration, in his confirmation hearings, spoke about the Trump Administration’s vision of world order. [He spoke] not about a liberal international order but about putting America and American interests first.20 The Biden Administration came in with an international vision structured around the competition between democracy versus autocracy.21 So Rubio is telling us that Trump 2.0 will have a very different framing of how the United States sees the world. I think India will find this new framing reasonably comfortable. But when you're talking about American primacy, India has its own aspirations and ambitions. India is not in the game of supporting American primacy per se. India will see certain utility in working with a powerful and prosperous America but that's not its goal. There will be some natural limits to where that partnership can go under these new terms.

SS: I wanted to raise two points in response to what you just said. First is this idea of ‘strategic altruism’ that Ashley Tellis has previously written about.22 How does one make sense of that under a transactional U.S. president? Secondly, I think any concerns India might have had about the U.S. government raising human rights issues need only look at the Trump administration’s response to the 2020 Delhi riots that were happening right around the time when the former President was on a visit to India…

DM: I’ll start with your first point. The practical implication of Trump being less inclined to “strategic altruism” could be felt in tangible ways, say with the GE jet engine deal, and more generally in terms of whether the United States is willing to engage in co-production agreements that transfer technologies to India because they're good for India.23 Or to see India's concerns about job creation and job protection as America's concerns. I don't think that the Trump administration will take that line. Even though Trump 2.0 may come around to the notion that you know a GE jet engine deal that makes jobs for Indians but also makes money for GE is a good thing for America. But they'll need to be convinced of the argument in ways that I think are different from how the Biden administration could be convinced of the value of such arrangements.

Trump 2.0 & Afghanistan —

SS: Elizabeth, you wrote this interesting piece with Sania Shahid where you spoke about how a second Trump administration might engage with Afghanistan. Sania and you argue that a second Trump administration “is likely to be less willing to coordinate with other international stakeholders on Afghanistan, risking further fracturing of existing diplomatic efforts.” How do you think Trump 2.0 will engage with Afghanistan, if at all? I also want to point out that the Indian Foreign Secretary recently met with the Taliban so if you can speak on the issue of recognition as well…

ET: So this is not the response you're looking for. I think this really is one of those [issues] where time will tell. You have a few duelling interests and perspectives that I think we can probably identify heading into the new administration. So you have a National Security Advisor, who himself is a veteran with combat experience, and has been quite outspoken and critical of the Biden administration's withdrawal from Afghanistan in terms of the process. You have the fact that the Trump administration and Zalmay Khalilzad negotiated the Doha agreement back in March of 2020. Of course it wasn't the Trump administration that was in office during the withdrawal, but there was a clear line from one to the other. You have other duelling interests… competing bigger picture geopolitical themes. So U.S.-China competition is not something that has been prominent in the Biden administration's approach to Afghanistan. I hosted then special representative Tom West back in August of 2023 at Stimson for a conversation. I asked for the U.S. perspective on Chinese investment and activities in Afghanistan, and he was very explicit that the U.S. did not see Afghanistan through a great power competition lens.24 We now have a sitting Taliban ambassador in Beijing, and though China is taking a very slow and cautious approach in many ways, things have moved over the course of the last 4 years. You also have the CT [counter-terrorism] issue, which certainly came to the fore back in March of last year, when we saw the IS-K [Islamic State-Khorasan] attack in Moscow that got a lot of attention. We saw the over-the-horizon strike against [Ayman] al-Zawahiri in Kabul during the Biden administration. Additionally, what the Biden Administration read as a regional CT threat from groups like the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan is quite significant now. The CT threat that is coming up in Pakistan is concerning, and though it so far remains largely restricted to the border area between Pakistan and Afghanistan, I think that's something the U.S. needs to keep an eye on. So from that mix of competing interests and prerogatives and personalities… To be honest, it is a little difficult for me to read the tea leaves on which of those is going to come to the fore. I haven't mentioned inclusivity and the question of women and girls education and role in the workforce. There was certainly a lot of attention to that under the Biden Administration that may well continue. It will to an extent depend on who ends up running lead on Afghanistan policy, and how prominent an issue this really is. I think that question remains to be answered. I would not expect that Afghanistan, barring some catastrophic events, is going to be very high on the Trump administration's to do list. If that's the case, it might look a little bit more like continuity than taking a very swift turn one way or another. But it’s worth watching this space because it could be a litmus test for how the Trump administration is going to rack and stack these competing priorities, and certainly one that has political implications here at home given the conversations that have happened on the hill about the withdrawal and the Biden administration's role. I know that's not a terribly satisfying answer but I think it'll be quite interesting to see going forward.

A last very brief point, bringing in the international angle that you asked about. So, as I noted, we already have de facto representation in Beijing. You referenced the Indian meeting [see Figure 10]25… it feels like this international consensus on at least a de jure non-recognition [of the Taliban] is weakening, and that is probably reflective of the reality of the hold that the Taliban seem to have on power now three and a half years after their takeover. There are not a lot of forms of leverage with the Taliban… Recognition might be one but as soon as that international consensus continues to break down further, it feels like this is going to be a moment where we could see several countries break ranks [on the Taliban recognition issue] over the course of the Trump administration, and so I will certainly be watching closely how the U.S. plays that, and the extent to which the Administration perceives that there might be a deal to be made here.

U.S.-China ties -

SS: I appreciate that you spoke about what is happening to women and girls in Afghanistan. As an Indian citizen, I don’t understand why the Indian government isn’t doing more to support Afghan students [I have written about this before; see here and here]. I wanted to switch gears and talk about China. It has featured quite a bit in our conversation already. We know that the Trump administration crafted its Indo-Pacific policy keeping China front and center. In the second Trump term, some scholars have raised concerns about what this relationship might look like under Trump 2.0. Tanvi Madan, at the Brookings Institution, wrote that there might be “uncertainty about Trump’s China approach - the possibility of him seeking a deal with Xi Jinping - and his commitment to working with allies and partners in the Indo-Pacific.” Dan, you have studied this subject extensively [see Figure 11]: what are the possible scenarios for a U.S.-China relationship and how might this shape India-U.S. ties?

DM: Sure. So you're right, and I’ve heard it many times… a concern in New Delhi about a potential G2 [between the United States and China].26 But likewise there's always some concern here in Washington that India will find its way back into a closer relationship with China. So these anxieties will persist until or unless the United States and India are in some kind of a full anti-China binding alliance which I don't anticipate. So let's just say that both sides are concerned about what might happen. At the same time, the reality here in the United States is that concerns about competition with China, and possibly worse, have only hardened over the past four years. If there's a bipartisan consensus on anything in the world, it is that China poses a challenge, possibly a threat to a range of U.S. interests. A trade deal, would certainly alleviate certain types of concerns with China [but it] wouldn't alleviate all concerns with China. Just like India having a narrow tactical deal to resolve its border tensions with China along the Line of Actual Control doesn't resolve India's deeper strategic concerns about what China may be doing in its neighborhood or [in] the wider world. This doesn't fundamentally alter the nature of the relationship. So what are the scenarios? I mean, you could get a slight mellowing by way of arrangements, like a trade deal, between the United States and China. That would look like a slight mellowing over the course of the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union. Not a change in their adversarial stance at some fundamental level, but an agreement not to make certain parts of that competition more acute, or an agreement to pursue mutual interest in certain ways. Of course, the Cold War analogy doesn't always hold because the United States and China, unlike the United States and the Soviet Union, are really entangled in mutually beneficial economic ties. That said, I think the general consensus here in Washington is that we are likely to see a competition that may go on for many years between the United States and China, and that we'll be lucky if we can manage that competition in ways that doesn't get too hot, and if we can avoid a hot war over something like Taiwan. The past few years really have been noteworthy for the degree of concern here in the United States, particularly in the Defense Department [but also] other parts of the U.S. government about the possibility that we could tip into a hot war with China and the possibility that the United States is not as well placed as it needs to be to deal with that potential scenario. Those are the scenarios that seem most front of mind for most American analysts.

What's absent from that type of thinking about China? There are scenarios that I think are a little bit closer to the front of mind for many Indian analysts, who sense that we are entering or have entered a multipolar world, one in which other players, including India, but also Europe and Russia, and to a lesser extent, say Turkey or Iran, really have a lot more say, in the nature of global affairs. So the United States still finds itself thinking about scenarios in a relatively more simple bipolar order, whereas I think many in the rest of the world are playing with these more complicated multipolar scenarios. I think that's important… Important for the United States to appreciate how others are coming to this situation, and important for others to recognize how Washington is likely to see things in a more starkly bipolar context.

SS: Staying on the subject of U.S.-China and India-U.S. ties… Elizabeth, you co-authored a piece advocating for a standalone South Asia policy alongside a broader Indo-Pacific strategy that was published in November 2024. You recommend that President Trump’s team could develop a “standalone strategy for South Asia alongside its broader Indo-Pacific goals” as a “South Asia strategy would provide a space for the administration to fully define its policy toward India beyond its role in the China context,” it would “provide top-level policy guidance on all the countries in the region, including Pakistan and Afghanistan” and crucially, “a separate regional policy would allow the administration to define U.S. goals in the region beyond those driven by competition with China.” Could you expand on this?

ET: I think there's no denying that U.S.-China competition is the shaping frame that is likely to endure over the course of the Trump Administration as Dan just laid out. I worry that with the current policy framework under the Indo-Pacific strategy, there are a couple of challenges [that are] both regional and functional that could be better addressed by a region-specific South Asia strategy. The idea isn’t to replace the Indo-Pacific strategy but instead to outline regional priorities that would supplement it and better represent the full region and full scope of U.S. interests. Right now, the Indo-Pacific strategy does not speak to either Pakistan or Afghanistan, and they aren’t included in any other region-based strategy, despite being states that impact U.S. interests in a variety of ways. So I think we need to have a conversation about where and how they fit, not least given China’s deep ties with Pakistan and growing footprint in Afghanistan. On the functional side, while U.S.-China competition is a very important challenge and one that will continue to drive U.S. policy throughout the region, We need to also have a way of factoring in issues like non-proliferation and counterterrorism that will continue to matter for U.S. interests. We need to better identify areas of overlap among those interests and to clarify priorities and tradeoffs where they don’t align. Then there's also the question of how we approach the broader region. Even just in the last year we've seen several surprises from the smaller South Asian states. I worry that having a publicly enunciated framework that is so primarily focused on competition with China limits our options in how we relate to those smaller South Asian states who themselves are largely very wary of camp politics, and are trying to hedge a bit between the U.S and China. There are perhaps opportunities there that are missed. One last point is that India’s role within the region and beyond has grown immensely in ways that aren’t fully captured in the Indo-Pacific strategy. Those elements of cooperation between the U.S. and India that extend beyond the region or aren’t primarily motivated by competition with China might be better captured in a strategy that speaks to the countries of the region than by the existing Indo-Pacific strategy in isolation.

Recalling that the first Trump administration had both an Indo-Pacific strategy and a South Asia strategy, what I was hoping to do in the piece was start a bit of a conversation of the ways in which we can potentially leverage a return to that model. Time will tell how the incoming administration approaches this. I do think, though, that it's important to recognize the centrality, not just of competition with China, but of the other interests that the U.S. carries in the region, and to find a way of ensuring that those are aligned when possible and prioritized when not.

U.S. politics & policymaking -

SS: A final question for both of you. Given your extensive government service and work on U.S. foreign policy, from your perch in D.C., what is something that policymakers and scholars from India should keep in mind regarding a second Trump presidency? Dan, if I could ask you to go first… Could you also speak about areas of foreign policy consensus between Democrats and Republicans in the polarized political landscape in the United States, and your thoughts on the limits to executive action?

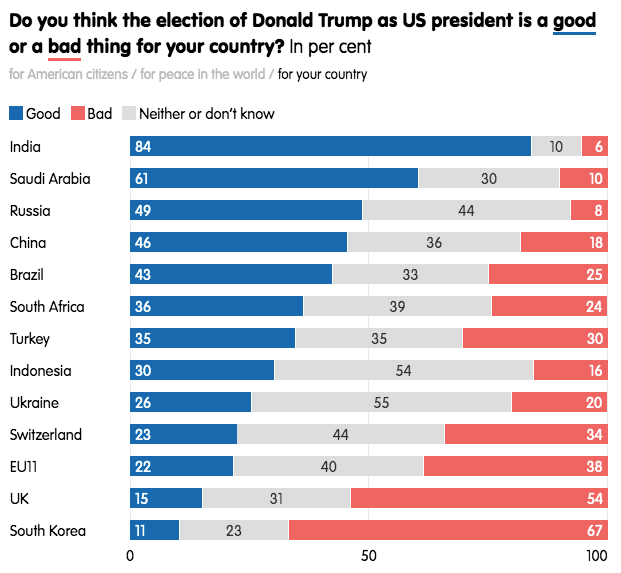

DM: Sure, couple of things. So the first question being - what Indian policymakers or policymakers in the region should be keeping in mind. My answer is a reflection of my concerns about what I hear from experts in India. I think they are significantly downplaying the potential for real uncertainty as to what the Trump Administration will bring in terms of its foreign and domestic policy. There is a reason why Americans who work on domestic politics are struggling to predict what will happen next. The uncertainty is deep and profound. What I hear from a number of Indians, is a sense that well, we know Trump from his first term and we can broadly manage that because we did a pretty good job before. And I understand that view, but I also think that the idea that this is just American “politics as usual” is too superficial. Yes, administrations come and go. Sometimes Democrats and Republicans are not all that much different. And some of Trump’s differences are about style more than substance. And, as we’ve already seen, there was a fair amount of policy continuity in Trump’s first term on a variety of issues. But that interpretation of Trump really underestimates two things. One, the areas in which there was a discontinuity… Think about North Korea for example. You know there was a willingness to do things that were profoundly unusual, not just in terms of style, but in terms of substance and process. There is an idiosyncratic element to behavior that is unique to this incoming President that we have not seen before in the American Presidency. Indians are not unique for underestimating Trump as an agent of change. We see polls from across Asia that reflect similar views, and I think that needs to be rethought a bit. My concern, if it's not rethought, is that people will be surprised when things happen that they didn't anticipate. I think we should all be alive to the possibility that this incoming administration will take many steps that we won't have anticipated. So that's point one. Point two: there is a lot of consensus, as I mentioned before here in the United States, between Democrats and Republicans, on China. More so than on most other foreign policy issues. But the consensus is not because everybody agrees on everything about China. It's a consensus that reflects concerns about China's trajectory from people who are worried about what China will do to us [the United States] economically, from other people who are concerned about things like human rights or labor, from other people who are worried about what China may do in terms of its region, like on Taiwan or the South China Sea…. It therefore brings together many different constituencies in a fairly stable coalition at the moment which should lead the United States and the Trump administration not to dramatically veer away from a competitive China strategy or set of policies. But it's like any other political consensus. It's founded on a variety of different motivations and incentives.

Last point in terms of limits on executive action. You know we're not a parliamentary system, and because of that our separation of powers grants considerable power to Congress. The judiciary can also override executive power, hem it in, constrain it. The President is not a king. However, this is a President who comes in with both Houses of Congress of the same party, and this is a President who has taken his party and made it his own in ways that not every President has. In other words, members of Congress, senators… Republicans [who] see themselves as beholden to this President are more inclined to submit to his will than they have been, say, than Democrats were [beholden] to Biden or to Obama in previous administrations. So President Trump is very powerful now, and we don’t know precisely the limits of that power, in part because even the composition of the Supreme Court has shifted. So even there, the constraints may be somewhat looser than we might have expected historically. However, this won't last indefinitely. There’s always another election and our elections happen pretty frequently. So basically, I would say, this administration has about 18 months of being about as powerful as we can expect it to be, and then we don't know. In 18 months the House of Representatives and part of the Senate will go back to the polls, and if the Trump administration has done things that are seen as effective, it will be rewarded, probably, in which case it will continue to enjoy this kind of power throughout the most of the four years of its term. If not, Trump will be a lame duck president, with no constitutional prospect of running again and that will undermine his political power at home for those next two years, and there will be further constraints from that. So both institutionally and politically he will be constrained in what he can do. That's just the normal way American politics works… that’s not specific to him, but I think that's worth keeping in mind. So the next 18 months we could see a lot of change… it looks a little bit more like a parliamentary system where a lot of power has been consolidated into relatively few hands. So that'll be an interesting time but that doesn't necessarily go on forever.

SS: Thank you, Dan. A similar question for you Elizabeth with a slight change. What should scholars in Pakistan and policymakers in Islamabad keep in mind while engaging with Trump 2.0?

ET: So on the Islamabad bit… What I have been hearing is a bit of the conventional wisdom that has prevailed in Pakistan over the course of changes in administrations, which is that Republican-led administrations tend to be friendlier towards Pakistan than Democratic administrations. My sense is that policymakers in Pakistan have largely attributed [this to] the Biden administration's lack of high level attention to Pakistan, lack of engagement, reduced funding levels, [and] critiques on a host of issues. The hope that an incoming Trump administration will be friendlier towards Pakistan is a kind of a reversion to this norm. I would differ from that interpretation of how this is likely to play out. My read at least, is that much more significant is the end of the war in Afghanistan, and [we’re] really entering an era where Pakistan finds itself in fairly close alignment with China. The U.S. and Pakistan are in many ways on different sides of this broader geopolitical competition. Pakistan is, of course, very careful to say that it is not choosing sides. The perception among policymakers in Washington tends to be that it is certainly moving closer to China. So if you are in a situation where you have both that lack of alignment on great power competition and you not longer have the war in Afghanistan holding these two sides [Pakistan and the United States] together with the war in Afghanistan removed, I would not foresee a significant, positive turn in U.S.-Pakistan relations under the Trump administration. You know there there could be slight differences in focus, and certain issues will receive more and less attention. There's been an interesting focus on the Imran Khan issue that has been driven in large part by the diaspora supporters of PTI and Imran Khan, and some attention to tweets that have gone out from incoming administration officials. I personally wouldn't expect much to come of that necessarily. I think one element that we haven't really touched on as much is the extent to which both social media and diaspora communities in the U.S. are bringing domestic political issues in South Asia into U.S. politics. For example, Representatives on the Hill are hearing about these issues from their constituents. So over the course of the next four years [this] could be a trend to watch where we’re likley to see a blurring of foreign and domestic politics in a way that feels new and could complicate U.S. policy in the region. I would very much agree with Dan's assessment that we really should prepare ourselves for uncertainty, and it is genuinely difficult to predict which way things are likely to head. The glass half full version of this is that I really encourage regional policy makers to be alive for opportunities to engage with the new administration that can be framed as in line with U.S. interests. As we’ve seen in other regions, for example through the Abraham Accords, conventional wisdom and policy lines the U.S. had maintained for decades suddenly changed. With that, and with broader realignments, can come moments of opportunity. They can also bring some challenges, and I don't want to underplay those. I think one thing, though, to end on is just the process side of things and style wise how this administration is likely to be quite different. As Dan alluded to, certainly the Biden administration ran a very tight process-ship and we saw [this] in areas of the U.S.-India partnership that required a lot of diligent work within the bureaucracy. There was progress made there. So it is worth watching from a regional policymaker’s perspective how the Trump administration wants to do business this time around, how much of this is going to be driven by top level engagement between Trump and his counterparts, what changes are made at the levels of the State Department, for example, that could have an impact on how the U.S. does diplomacy abroad… There could be second order impacts from some of the administration’s government reform initiatives that would shape how relationships in the region are managed, and I think that's something that I haven't seen as much focus on, and is worth some attention going forward.

SS: Thank you so much. We’re right on time, and this is a good place to end the conversation…

DM: Shreyas, before we end the conversation, can I jump in on a couple of things …

SS: Absolutely, please do…

DM: Elizabeth said a lot of really good things on Pakistan, and I haven't said much on Pakistan. I did want to just add a couple of points there mainly in agreement, which is to say… First, I agreed with her broader point about needing, say, a Pakistan [specific or a] South Asia strategy, one that is somewhat related to, but maybe distinct from a broader Indo-Pacific, or even China strategy. One reason for this is that Pakistan needs to understand where, if at all, it fits into an American strategic vision. No one has had an answer to that question. Left without an answer, it’s not surprising that the natural inclination for Pakistan [is] to draw closer to China. I mean, there's no alternative. I don't know what to tell Pakistanis when they ask me where Pakistan fits into American strategy in Asia or the Indo-Pacific, or globally, except to say that there's a lot of concern about Pakistan here [in the United States]. To follow up on that point I would say one specific thing that the Biden administration leaves office having voiced concern about is the idea of Pakistan developing a long-range ballistic missile for which it's being sanctioned… or entities are being sanctioned. I think the Biden administration has every intention of leaving that in the incoming Trump Administration's lap and saying, ‘You need to do something about this.’ So that’ll be on the agenda for any future Pakistan [strategy]… likely at its core. One last observation. It seems odd to me that many Pakistanis say that Republican administrations are better for Pakistan and many Indians also say that Republican administrations are better for India [see Figure 12]. There are few things that the United States can do that are better for both India and Pakistan at the same time. So I wonder what to make of this. Let's just say… count me skeptical about these perceptions. I would add that while Trump is a Republican, he's broken with many of the past practices of the Republican party. To cast Trump as a traditional Republican would be to seriously miscast him and to miss what's going on in American politics, which is different from what's happened in the past, and which will have consequences for many things, including how he works with India and Pakistan.

III. Further reading –

India-China ties:

Journal article on the ‘Sino-Indian Boundary Dispute, 1948-60’ by Srinath Raghavan for the Economic & Political Weekly. [September 9, 2006]

Study report on ‘India-China Bilateral Trade Relationship’ prepared for the RBI by S. K. Mohanty. [January 2014]

IISS Fullerton lecture by former Foreign Secretary and current Foreign Minister S. Jaishankar [July 2015]

In this Brookings Institution article, Tanvi Madan notes that at the inaugural Raisina Dialogue in 2016, Indian officials “[w]ithout once naming China,” presented “Delhi’s perception of that country’s connectivity initiatives and contrasted the Chinese and Indian approaches to connectivity and the region” with then External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj stating that “We [India] bring to bear a cooperative rather than unilateral approach and believe that creating an environment of trust and confidence is the pre-requisite for a more inter-connected world.” [March 2016]

Report tracking ‘Chinese Investments in India’ authored by Amit Bhandari, Blaise Fernandes, and Aashna Agarwal for Gateway House. [February 2020]

Brookings India report by Ananth Krishnan, ‘Following the Money: China Inc’s Growing Stake in India-China Relations.’ [March 2020]

A media report from the depths of the 2020 border crisis documents how India ‘scrambled’ to buy winter gear from U.S. and how a foundational agreement signed in 2016 (the Logistics Exchange Memorandum of Agreement, LEMOA) enabled this. [October 2020]

Paper on the ‘Future of India-China Relations’ after Galwan by Vijay Gokhale for Carnegie India. [March 10, 2021]

Note on why India and China are unlikely to reach a ‘Strategic Détente’ by Saheb Singh Chadha for Carnegie India. [August 29, 2023]

Transcript of Tanvi Madan’s ‘Global India’ podcast episode with Ashok Malik on ‘India’s economic ties with China: Opportunity or vulnerability’ for the Brookings Institution. [November 15, 2023]

C. Raja Mohan argued that India should “stay the course with its current approach to China” and not rethink its policy of resuming “political and economic dialogue with China until the military confrontation in the Ladakh frontier, which began in the spring of 2020, is resolved to its satisfaction.” [November 22, 2023]

Fascinating ground reportage on Foxconn’s experiences in establishing a plant in India to build iPhones by Viola Zhu and Nilesh Christopher for RestofWorld. [November 28, 2023]

India-U.S. ties:

Dennis Kux’s India and the United States: Estranged Democracies, 1941-1991 [1992]

Prime Minister Vajpayee’s speech on ‘India-U.S. relations’ at the Asia Society where he said: “The range and frequency of the India-US dialogue has increased considerably in recent times. It covers global and regional matters, as well as long term and near-term issues. But most significantly, it is the atmosphere of our dialogue that has changed. We now address each other with the confidence and candour of friends. This dialogue, based on respect and equality, is successful precisely because we have recognized that there is no fundamental conflict of interest between us. We work together on areas of agreement, and frankly discuss our differing perceptions, without this affecting our relationship. This reflects the growing maturity of our friendship.” [September 2003]

Druva Jaishankar’s report on ‘India and the United States in the Trump era: Re-evaluating bilateral and global relations’ for the Brookings Institution [2017]

A H-Diplo article by Tanvi Madan on the first Trump administration and its relationship with India. She writes “By the end of the Trump administration, India had a healthier portfolio of partners, one that did not preclude but, in fact, included a much closer defense and security relationship with the United States. The India-U.S. partnership that the Biden administration inherited was in a much better place than many other American relationships. In certain realms, it was also in a better place than it had been at the end of the Obama administration. The relationship thus did not require repair as much as rebalancing. And the new administration has broadened the areas of cooperation, while continuing to build on the strategic convergences that have been apparent since 2000 and intensified during the Trump years.” [November 2021]

Congressional Research Service report on India-U.S. ties [July 2021]

What is the United States-India Initiative on Critical and Emerging Technology (iCET)? by Rudra Chaudhuri for Carnegie India [February 2023]

‘The Trump factor in Indo-US energy ties,’ by Richa Mishra for The Hindu BusinessLine [November 2024]

‘In DC-Delhi warmth, cold light: Trump may look for Indian ‘pro’ for American ‘quid’’ by C. Raja Mohan in the Indian Express [November 2024]

Rick Rossow writes “The American approach to relations with India may again shift to become more transactional. But the significance of the partnership was well-understood by officials in the first Trump administration and supported by President Trump himself, allowing both sides to manage areas of friction while seizing opportunities to deepen cooperation” for CSIS in this piece titled ‘U.S.-India under Trump 2.0: A Return to Reciprocity’ [November 2024]

Tanvi Madan’s Foreign Affairs piece on how ‘India Is Hoping for a Trump Bump’ [December 2024]

U.S.-China ties:

See this policy brief on ‘Principles for managing U.S.-China competition’ by Ryan Hass for the Brookings Institution [2018]

This CFR blogpost on the U.S. trade war with China notes, “As China has cut its U.S. imports, it has bought commensurately more from the rest of the world. In particular, it has expanded trade with countries participating in its massive “Belt and Road” investment initiative (BRI).” See, ‘Trump’s Trade War Puts “Belt and Road First”,’ by Benn Steil and Benjamin Della Rocca [August 2019]

The first Trump administration’s ‘Approach to the People’s Republic of China’ policy document [2020]

‘Imagining the endgame of the US-China rivalry’ by Michael Mazarr published in Engelsberg Ideas is a must-read [2024]

U.S. Politics:

Alan I. Abramowitz and Steven Webster’s ‘The rise of negative partisanship and the nationalization of U.S. elections in the 21st century’ in Electoral Studies [2016]

Douglas Irwin’s Clashing over Commerce: A History of US Trade Policy [2017]

Phil A. Neel’s Hinterland: America’s New Landscape of Class and Conflict [2018]

Dylan Riley’s note on ‘What is Trump’ for New Left Review [November-December 2018]

This PBS Frontline documentary on Trump’s Trade War goes in-depth on the ideological clashes that occured with regards to Trump 1.0’s trade policy and approach to China - a lot of the key characters appear for interviews [May 2019]

Why We’re Polarized by Ezra Klein [2020]

An excellent, wide-ranging interview with Ted Fertik, Daniela Gabor, Tim Sahay and Daniel Denvir on ‘Defining Bidenomics’ published by Phenomenal World. Tim Sahay noted that “Bidenomics is a new legislative and macroeconomic policy mix, developed by Democratic Party elites to contain the threat of Trumpism. It’s their answer to the question social democrats are asking the world over: Why can’t the center hold? Their diagnosis is that economic and political polarization was created by the winner-takes-all, low investment, low growth, neoliberal policy regime. The gap between those with and without college degrees widened (that’s the class component) along with the gap between “Super Zips” and suburban and rural areas (that’s the place element), which created political instability.” [September 2023]

Adam Tooze on ‘The Democrats’ Defeat’ for the London Review of Books where he writes: “In 2020 what America needed above all was to be reassured that normality was still within reach. But as Biden’s term went on, what came increasingly to the fore was his version of returning the US to its pre-Trump greatness. The Biden presidency was restorationist and Harris promised to continue in that vein. Essentially, they wanted to rerun 2020 and found themselves, instead, in 2016. They were defeated by Trump’s charismatic, free-wheeling, undisciplined promise of nationalist, xenophobic, racist and misogynistic radicalism. It may be that by 2026 the electorate will have tired of this.” [November 2024]

One of the most interesting conversations I have heard on the ideoogical roots of the MAGA movement is this one on ‘the Dig’ featuring Quinn Slobdian and Wendy Brown [November 2024]

Wired magazine has a bunch of articles on folks who are tied to Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) and the changes they are making in the government. See the opening line in this report: “A 25-year-old engineer named Marko Elez, who previously worked for two Elon Musk companies, has direct access to Treasury Department systems responsible for nearly all payments made by the US government.” [2025]

Nathan Tankus’ ‘Everything about the Trump Administration’s impoundment putsch you were too afraid to ask’ in Crises Notes [2025]

Kate Mackenzie, Tim Sahay, and Lara Merling write, “The United States will be a source of chaos and volatility for the next several years. The first month of 2025 has set the scene. Events so far have included imperial gangsterism against both a poor Latin American country (Colombia) and a rich northern European one (Denmark); a long-overdue ceasefire ending a genocidal military campaign (Gaza); the most expensive natural disaster in US history with climate-fuelled wildfires destroying homes (California); a trillion dollar sell off in the AI bubble in reaction to a Chinese firm’s innovation from behind the chips blockade; and the outbreak of a virus (H5N1) that has killed hundreds of millions of US poultry, sending egg prices soaring and raising concerns among scientists of another pandemic. OK, doomer” in this excellent Polycrisis piece published by Phenomenal World. [2025]

The Financial Times has a great set of reports that points to the volatility surrounding the current administration. See this one on 72 hours of trade chaos, a piece on economic uncertainties, a conversation with Dani Rodrik on making sense of Trump’s tariffs, a report on entanglements with cryptocurrencies, and the government’s revocation of President Biden’s security clearance. [2025]

T. J. Clark’s ‘A Brief Guide to Trump and the Spectacle’ for the London Review of Books where he concludes: “If Trump is what the image-world has now revealed itself to be – if he’s the ‘society’ we have settled for, looming against us, cruel and false and ugly and determined to destroy – then what answer is left but a fight to the finish? A plan of campaign, with spectacle the enemy. Not derision but tactics.” [January 2025]

Those who believe that the immigration issue is contained in the digital sphere and/or somehow resolved, should pick up Elle Reeve’s Black Pill: How I Witnessed the Darkest Corners of the Internet Come to Life, Poison Society, and Capture American Politics. In a Vox ‘Today, Explained’ episode Reeve highlights how some of the “old alt-right guys have been complaining that normy conservatives, the MAGA movement, stole all their ideas and they didn't get to be part of this, you know, this triumphant Trump movement. They were pushed to the side, and yet Elon Musk is reposting their memes from 10 years ago.” Some of the alt-right ideas that emerged and spread online “have been incorporated into mainstream Republican politics” including a version of the “great replacement” theory.

At the White House meeting, Trump offered to “mediate in the Indian-Pakistan conflict in Kashmir” and said that India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi requested that Trump “mediate or arbitrate” in the dispute. The Indian government responded by stating that “no such request” had been made to Trump noting that all issues with Pakistan were “discussed only bilaterally.” Dissecting where trouble could emerge for South Asia under Trump 2.0, Suhasini Haidar wrote that Trump has a “habit of disclosing the contents of private conversations with leaders and, on occasion, embellishing them or even imagining them” citing Trump’s Kashmir mediation offer as an example. Touqir Hussain, a former Pakistani diplomat, astutely noted that Trump’s offer on Kashmir should not be taken seriously as “the offer had nothing to do with Kashmir. It was about himself [Trump]” and Trump wants to “appear to his base as a popular world leader being looked up to by other countries to solve complex disputes.”

In an interesting turn of events, advisors close to Trump demanded the release of former Prime Minister Imran Khan. A media report highlighted the “deep irony in the PTI [Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf], the country’s most popular political party, trying to lobby the US for help - less than three years after it accused Washington of a role in Khan’s removal.”

This 2016 Brookings Institution article by Tanvi Madan has a succinct overview of the Indian government’s initial reactions to China’s ‘One Belt, One Road (OBOR)’ initiative. Madan notes that at the inaugural Raisina Dialogue, the Indian government “signaled Delhi’s concern about Beijing’s approach toward connectivity and the region more broadly.” Also see these remarks from 2015 by then Foreign Secretary and now Foreign Minister Dr. S. Jaishankar on the OBOR/BRI [46:00 mins onwards]. India continues to refuse endorsement for the initiative pointing out that any mega connectivity project must respect sovereignty and territorial integrity.

The first Trump administration’s ‘Approach to the People’s Republic of China’ policy document makes this clear, noting: “One Belt One Road (OBOR) is Beijing’s umbrella term to describe a variety of initiatives, many of which appear designed to reshape international norms, standards, and networks to advance Beijing’s global interests and vision, while also serving China’s domestic economic requirements… The United States welcomes contributions by China to sustainable, high-quality development that accords with international best practices, but OBOR projects frequently operate well outside of these standards and are charecterized by poor quality, corruption, environmental degradation, a lack of public oversight or community involvement, opaque loans, and contracts generating or exacerbating governance and fiscal problems in host nations… Given Beijing’s increasing use of economic leverage to extract political concessions from or exact retribution against other countries, the United States judges that Beijing will attempt to convert OBOR projects into undue political influence and military access.” Then U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo stated that “China is using its government power through the Belt and Road Initiative to achieve its national security objective” asserting “that the Trump administration is leading global efforts to inform countries about the “predatory” Chinese economics.” A 2019 CFR post noted that China cut U.S. imports, “commensurately” buying more from the rest of the world, particularly expanding trade with “countries participating in its massive “Belt and Road” investment initiative (BRI).”

Writing on India-U.S. security ties, Joshua White (in this Brookings Institution paper) notes that “Building on the efforts of the Bush and Obama administrations, the Trump administration acted with uncharecterisic diligence to advance cooperation on a range of issues.” He writes that India and the United States signed the General Security of Military Information Agreement (GSOMIA) in 2002, the Logistics Exchange Memorandum of Agreement (LEMOA; previously the Logistics Support Agreement, LSA) in 2016, the Communications Compatibility and Security Agreement (COMCASA) in 2018, an important industrial annex to the GSOMIA in 2019 and the final major agreement, the Basic Exchange and Cooperation Agreement (BECA) for Geospatial Intelligence in October 2020.

A Bloomberg report by Sudhi Ranjan Sen from October 2020 states: “India has bought high altitude warfare kits from the US on an urgent basis, officials with the knowledge of the matter said, a sign that the South Asian nation is preparing for an extended winter deployment after talks to ease tensions along its border with China stalled. The Indian Army used an agreement which allows the two militaries to take logistical assistance from each other such as buying fuel and spare parts for warships and aircraft, for the transaction, the officials said, asking not to be identified given rules for speaking to the media. The Logistics Exchange Memorandum Agreement signed in August 2016 aims to promote interoperability between the two militaries…. The rush to acquire the gear shows the situation will extend into the winter. The troops face off at 15,000 feet, with temperatures dropping to -30 Celsius (-22 Fahrenheit)... India until now sourced high-altitude kits for its defense forces mainly from Europe or China. S. K. Saini, the second-highest ranking general in the Indian Army, is on a scheduled visit to the US Army Pacific Command to discuss other emergency purchases and building capabilities. The Indian Army did not comment on the high altitutde warfare kits, but confirmed the visit of one of its top generals to the US.” [emphasis added] In April 2023, the Commander of the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, said that “India and the United States are facing the same security challenges from China” pointing out that “the Biden Administration is not only providing assistance to New Delhi with cold weather gear, as it defends its border on the northern side, but also helping India in its effort to develop its own industrial base.”