Policy Playbook #2: India, the UN, and the International Order with Rohan Mukherjee

A brief introduction to the UNSC reform debate, an interview with Rohan Mukherjee on India's relationship and history with the UN and the international order, and more.

I. A brief introduction to the UN’s ‘Summit of the Future’ and India on UNSC reforms:

In 2020, months into the COVID19 pandemic, United Nations (UN) Secretary-General Antonio Guterres said “the pandemic is a clear test of international cooperation – a test we have essentially failed.” 2020 marked the 75th anniversary of the UN’s founding, and in this landmark year, “tensions were on display at a Security Council meeting” at a time of geopolitical churn, as the United States and China, according to a media report from the time,

“… accused each other of mishandling and politicizing the coronavirus. Russia backed Beijing, a close ally, as it has in recent years, leaving the U.N.’s most powerful body charged with maintaining international space and security more deeply divided and unable to address major issues, including conflicts like the one in Syria.”

It is against this background that Secretary-General Guterres called for a “rethink of global governance and multilateralism.” On September 21, 2020, the UN General Assembly adopted a political resolution commemorating the organization’s 75th anniversary and it is worth highlighting certain points from the resolution,

“There is no other global organization with the legitimacy, convening power and normative impact of the United Nations… The United Nations has helped to mitigate dozens of conflicts, saved hundreds of thousands of lives through humanitarian action and provided millions of children with the education that every child deserves. It has worked to promote and protect all human rights and fundamental freedoms for all, including the equal rights of women and men… the United Nations has had its moments of disappointment. Our world is not yet the world that our founders envisaged 75 years ago. It is plagued by growing inequality, poverty, hunger, armed conflicts, terrorism, insecurity, climate change and pandemics… Strengthening international cooperation is in the interest of both nations and peoples. The three pillars of the United Nations – peace and security, development, and human rights – are equally important, interrelated and interdependent. We have come far in 75 years but much more remains to be done… Through reinvigorated global action and by building on the progress achieved in the last 75 years, we are determined to ensure the future we want… We request the Secretary-General to report back before the end of the seventy-fifth session of the General Assembly with recommendations to advance our common agenda and to respond to current and future challenges.”

In keeping with this resolution, the Secretary-General released ‘Our Common Agenda’ – a report in September 2021. At the launch of the report, Secretary-General Guterres noted the inadequacies of the organization in responding to global challenges. “From the climate crisis to our suicidal war on nature and the collapse of diversity, our global response is too little, too late,” declared the Secretary-General.

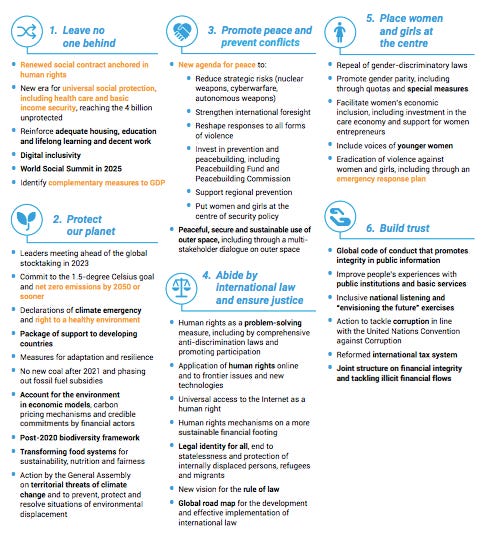

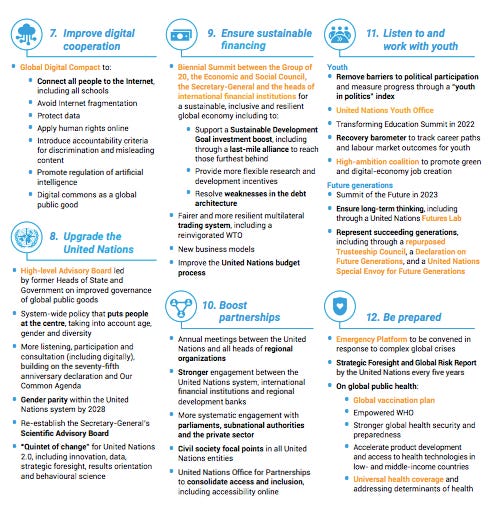

Described as an “agenda of action designed to accelerate the implementation of existing agreements, including the Sustainable Development Goals,” the report responded to 12 commitments [see Fig. 1 & 2] that were included in the political declaration adopted in 2020. Secretary-General Guterres noted that “in this time of division, fracture and mistrust, this space [the United Nations] is needed more than ever if we are to secure a better, greener, more peaceful future for all people.”

How was this to be achieved? Through the convening of a ‘High-level Advisory Board’ that would “identify global public goods and other areas of common interest where governance improvements are most needed, and to propose options for how this could be achieved,” alongside a range of actions including convening an ‘Emergency Platform’ (convened in response to complex global crises) and regularly issuing a ‘Strategic Foresight and Global Risk Report’ [see Fig. 3]. The Secretary-General also proposed a ‘Summit of the Future’ to “forge a global consensus on what our future should look like, and what we can do today to secure it.”

This ‘Summit of the Future’ just concluded in New York with ‘Action Days’ on 20th & 21st September followed by the two-day Summit. The UN adopted a ‘Pact for the Future’ alongside the ‘Global Digital Compact,’ and the ‘Declaration on Future Generations.’ This event, taking place right before the annual General Assembly, matters because, according to the UN, there is a “widespread perception that the structures of the UN, many of which were established decades ago, are no longer sufficiently fair or effective.” The Summit “offers a chance to deliver more fully on promises that have already been made, to ready the international community for the worlds to come, and to restore trust.”

The 2020 UNGA political resolution recognized the UN’s failures and the forward-looking Summit aims to respond to some of the long-running questions and concerns around the foundation’s legitimacy and efficacy [see Fig. 4].

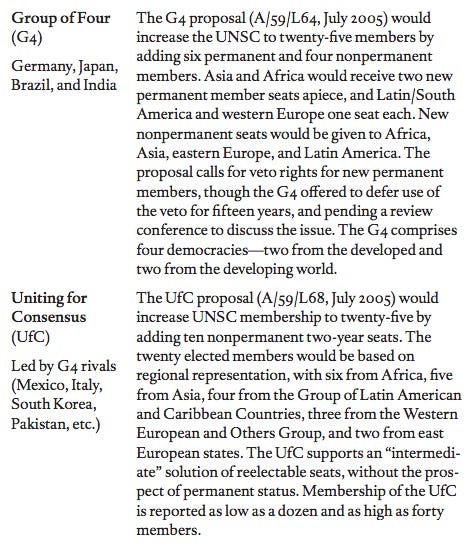

Sub-groups within the UN have called for reform, especially within the Security Council. One such sub-group is the Group of Four (consisting of Brazil, Germany, India, and Japan; see Fig. 5). In 2019, a German representative, speaking on behalf of the group, stated, “we have proven incapable of reforming the United Nations principal organ [the Security Council] for international peace and security,” and that we “collectively failed” in bolstering multilateralism.

India, as a member of the G4 and an UN member, has called for “reformed multilateralism” and consistently held this position for decades, expressing the same at times of crises. India’s representative at the UN in 2019, Syed Akbaruddin, called Council reform a “Sisyphean struggle” highlighting the lack of progress over decades given that it had been “11 years since the start of intergovernmental negotiations – and four decades since inscription of the item on the Assembly’s agenda.” In 2023, India’s representative at the UN, Ruchira Kamboj, stated “any further delay in Security Council reform exacerbates representational deficit” and that “calls for reformed multilateralism, with Security Council reforms at its core, are supported by the overwhelming majority of the [UN’s] membership.”

As scholar Rohan Mukherjee notes, “from India’s perspective, the current international order is inherently unjust” because the “distribution of power and moral authority in the world has shifted substantially since 1945.”

In this newsletter’s first edition I’d written about the 2023 G20 meeting and placed India’s G20 presidency in its broader global context. I highlighted India’s call for reforming the multilateral UN architecture,

In 2003, Prime Minister Vajpayee warned that “until the UN Security Council is reformed and restructured, its decisions cannot reflect truly the collective will of the community of nations”. In 2011, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh called for the reform and expansion of the UNSC to “reflect contemporary reality”. In 2023, at the closing of the G20 Summit, Prime Minister Modi urged leaders “to make global structures, including the UN Security Council, reflective of current realities”.

With long-running calls for reforms, concerns about the state and future of the international order, and the rise of powers such as Brazil and India, the 2024 Summit of the Future provides an opportunity to reflect on the international order, the order’s history, and India’s relationship with the order.

For the second edition of the ‘Policy Playbook’ I interviewed Dr. Rohan Mukherjee about the idea of a ‘liberal rules-based international order,’ the UN, and India’s place in, and vision for, the global order. Dr. Mukherjee is an Assistant Professor of International Relations at the London School of Economics and Political Science, Deputy Director of the school’s in-house foreign policy think tank, LSE IDEAS, and a Nonresident Fellow at the National Bureau of Asian Research (NBR) and the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

His research focuses on the grand strategies of rising powers and their impact on international security and order, with an empirical specialization in the Asia-Pacific region. He is the author of the award-winning book Ascending Order: Rising Powers and the Politics of Status in International Institutions and has published works in academic journals such as International Affairs, Global Studies Quarterly, India Review, and other publications.

This interview was conducted on September 13, 2024, and is (lightly) edited for clarity and brevity. Parts of the text (throughout this edition) are in bold for emphasis. I have included links and footnotes to provide context to some of Dr. Mukherjee’s points. Views expressed are personal.

II. Policy Playbook #2: India, the UN, and the International Order with Rohan Mukherjee

Shreyas Shende (SS): What is it about the current moment or the recent past that has prompted questions and concerns about the United Nations (UN) and the UN Security Council’s (UNSC) functioning? Or is this a question that suffers from presentism? Has this always been a concern, and we're just hearing more about it now?

Rohan Mukherjee (RM): It's definitely been a concern for decades. A lot of countries have been asking for greater representation in global governance, and on the UN Security Council and so on. You can think about the 1970s and the New International Economic Order (NIEO)[1], the discourse and movement that emerged among G77[2] countries back then. It's a lineage of that. There are moments where I think crises of the international order create opportunities for those calling for reform to speak more loudly about reform, but that conversation has been ongoing for a very long time. In these moments where the inadequacies of the international system and the international order, particularly the UN Security Council, are made very stark by things like, Russia's invasion of Ukraine, or if you think about the 2003 invasion of Iraq by the U.S. and its allies.[3] Those are the moments where the reform coalition that has been calling for reform says we need more legitimate, inclusive and representative governance otherwise you're going to end up with these kinds of situations. You're going to end up with flagrant violations of international law if you don't actually have a more representative system. So yes, it's presentism in that the urgency allows for that conversation again, but it's also this deep-seated call for reform that's been around for very long time.

SS: With respect to the history of UN and UNSC reforms, a number of steps have been taken with the aim to reform these institutions including the open-ended working group created in 1992 and the formal creation and authorization of the ‘intergovernmental negotiations’ in 2008. This 2008 body focused on the “question of equitable representation and increase in the membership of the Security Council and other matters related to the Council.” Stewart Patrick, writing about the UNSC reform, said the 1992 efforts were “aptly named” ‘open-ended.’ What has been the outcome of these processes and what does it say about the task of actually reforming the UNSC?

RM: At a very practical level, it's really, really hard to change the composition of the UN Security Council with respect to its permanent membership, because it requires an amendment of the UN Charter. This requires a very high threshold of support among countries around the world, plus ratification in their legislatures. So there's already this very high administrative bar, and that is deliberate, because you didn't want a situation like the interwar period where the League of Nations was hostage to a lot of politics between countries. So at one level, it's this institutional barrier. You don't want the UN Security Council's composition to change too easily, because you want stability in how it functions. You want the ability of the great powers that are in the P5 to be able to manage peace and security without feeling threatened regarding their own interests. There is the second issue, which is the deeper issue of how the international order is structured. It is this compromise between sovereign equality on the one hand and great power privilege on the other. As you know, because of the absence of world government, this is the way that states have figured out how to govern the globe, which is to have a group of powers at the top that have the privilege to run the system and can dictate rules to others, or at least set the terms, set the agenda and then have others sign on to it. There’s that uneasy compromise between sovereign equality and great power privilege that makes it very hard as well, because great powers are unwilling to give up their privilege. So reform is both politically difficult, but also institutionally challenging and difficult as well.

SS: These calls for reform have come from a bunch of actors, including India. You have written on India’s perspectives on the UNSC and its proposed reforms and you note that its official position is that it seeks “to correct three existing sources of institutional inequity: membership, formal powers, and informal powers.” Can you elaborate on these?

RM: The membership issue is pretty straightforward. It’s all about India's membership of the UN Security Council. Other countries also have asked for this, which is an expansion of the permanent and non-permanent membership of the Security Council. There are different formulations. India's [formulation for the UNSC] is currently at 26 [members, up from the present council of 15 nations], and that includes both permanent and non-permanent members.

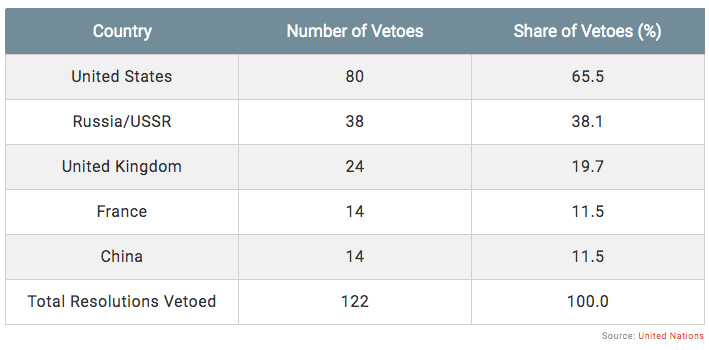

Then there's what comes with membership, which is formal veto power [see Fig. 6]. The formal side of it [involves] many other things, but the veto is the most important issue, in some sense. The P5 have veto power and India has asked for veto power for new permanent members, but also at the same time, a commitment by all powers, all members of the Security Council, permanent members in an expanded Council, old and new, to restrict their use of the veto to very extraordinary circumstances, to not use it to hold up the resolution of conflicts and peace and security efforts around the world. This goes back to the earlier point, which is about great power privilege. The UN Security Council works the best when its members are not trying to undermine it, or it does not actually involve a conflict that that infringes on the interests of one of the P5. So UN Security Council was gridlocked over the invasion of Iraq or the resolutions over Ukraine right now. U.S., Russia, other countries block resolutions that are not in their interest. Then there's this perception that the Security Council doesn't do anything. But that's not true, it actually does a lot of things. It's just that when it comes to these particular countries [the P5], the setup of the system prevents it from necessarily overriding their interests. So India would like that same privilege of having a veto on its own interests, but then it's also willing to commit, and wants everyone else to commit to using that [veto] in rare circumstances.

On the informal side, there's been the most progress. The Security Council has been rather aloof, historically, from the General Assembly, as well as [in instances where] countries whose cases have arisen in the Security Council. So India's position has been that there has to be more consultation, more involvement, more procedural openness, and the council should report more often to the General Assembly and so on. The working methods of the Security Council need to be more democratized – that's been India's position. I would say that that's where there has been movement [on the informal powers]. The other two issues [membership and formal powers] are still gridlocked.

SS: There are a number of major non-UN groupings like the G20 [formed in 1999 to bring together the 20 of the world’s largest economies; the G20 was elevated to the leader level with an annual summit in 2008], ASEAN, BRICS, and various trilateral groupings and mini-laterals in the Indo Pacific. Is it fair for me to assume that the emergence or rise of any of these groupings has anything to do with the perceived dysfunctionality of the international order? What does the rise or the endurance of these other non-UN groupings tell us about the international order? I would also like to understand India's space within these orders, because India is party to a lot of these non-UN groupings like the AIIB [Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank], BRICS, and so on.

RM: Historically, there's been lots of precedent for regional organizations and institutions to address regional issues. We have the European Union and its whole panoply of institutions that come under that structure. You have ASEAN [Association of Southeast Asian nations], Latin American institutions, the Inter-American Development Bank [IDB], OSC [Organization of Southern Cooperation] and all of that. There’s a lot of precedent for functional cooperation that is regional specific, or issue specific. So that's not necessarily new. What is new is this effort to create global parallels to what already exists. I wouldn't call them global parallels, but they are very ambitious parallels. The Shanghai Corporation organization [SCO],[4] the AIIB,[5] the New Development Bank [NDB],[6] BRICS[7]… these are the ones that are outside the core of the Western-led international order that have tried to create forums in which they [non-Western states] themselves have some amount of recognition and status.

You can see it in the way that these new institutions replicate the functions of the ones that already exist. So you think about the AIIB, it replicates a lot of what the World Bank does, but in Asia. If you think about SCO [Shanghai Cooperation Organization], you look at its charter, it looks very similar to the UN but it covers Central Asia and Asia more broadly. You may ask why are these institutions replicating what already exists. That doesn't make sense from a functional point of view. To me the answer to that question is that these are fundamentally social creations. Their purpose is to create those clubs in which these countries can feel that they have top billing because they're not getting it in the broader system because the US and its allies control so much. So one way to do that is to create these new avenues for recognition, status and a sense of leadership of the international order.

It's also telling that the capitalization of these new institutions is very low compared to the World Bank and the IMF and all these other IFIs [International Financial Institutions]. They don't wield the kind of financial power that those institutions do. Again, because it's replicating something, but more important, it's providing a new social arena for these countries. So it's not necessarily about providing development finance for Asian countries. It's actually about China deciding who gets that finance and who doesn't. So I think that's the distinction. In some sense, the lack of recognition or equality for these powers, for these countries of the global South, China formerly being of the Global South, although some would argue it still is [part of the Global South] but that is manifested in what you might call this institutional proliferation. Once you're denied in the mainstream, you start to create your own clubs. There's both that historical regional functional stuff, but then there's also this new status oriented set of institutions.

SS: In a 2019 piece for the International Security Studies Forum you argued that “rising powers such as China, India, and Brazil have benefited from the liberal order while criticizing it and even seeking to undermine certain aspects of it… It will take a great deal of creative thinking and diplomatic energy in these capitals to overcome long histories of reflexive free-riding and sniping at U.S. leadership from the sidelines. It is unclear if the rising powers are even up to the task.” Has your assessment changed in the past five years? I think this question is important because when you wrote the piece quoted above there was a Trump presidency, and there might be a second Trump presidency. What is your sense of this?

RM: I think a Trump presidency is more symptom than a cause of the broader change in the U.S. approach to the international order. There’s been a growing realization in American politics that you built this, this massive, global architecture of cooperation, but in the end, it ended up benefiting China, India, Brazil and other countries more than it did the U.S. That is by definition true, because they [these regional powers] have grown faster than the U.S. for the last 30 years. In a relative sense, it has empowered these other actors and threatened the United States’ position. So there's this questioning now among certain quarters in American politics… I mean, Ashley Tellis says this very often.[8] He says for the first time, there is bipartisan consensus in the United States that that trade is a bad thing. I'm paraphrasing him very poorly, but the point is that there's this anti-trade coalition that has emerged, and the US has blocked the WTO appellate body and judge appointments since 2019 and that’s remarkable.[9] Why is it that Biden has not reversed the things that Trump did. Yes, he re-joined the Paris agreement, but there's a lot of other things that Trump did which Biden has not reversed including on immigration but also on the WTO. There is a broader trend in American politics to look at the liberal order more sceptically because it has enabled the rise of China, India and other actors.

The question then becomes, as the US challenges, resists, perhaps even withdraws, from parts of the order, it creates opportunities for other states like China, India… and they have tried to fill those gaps. India has been very active in climate diplomacy, on the G20 front, and has done a lot of things in international development. There has been an effort to create more leadership positions for itself [India] … and this is where I think what I wrote in 2019 is still true, which is that it's easier to criticize U.S. leadership than it is to actually exercise the kind of leadership the U.S. does. To be number one in the system means being looked upon by other countries to solve problems that are not your own, and at the same time being criticized by those countries when you mess up in solving those problems. It is a crown of thorns. You have the privilege and the power to rule the world, but then you also have to absorb all the criticism of messing up, which you inevitably will do because it's impossible not to. There are no good choices in international politics, there are always trade-offs. Every humanitarian intervention, for example, creates losses of life.. You become the lightning rod of all the dissatisfaction in the international system. India is not willing to be that, and India is not willing to take on the responsibility yet of governing the world in a way that requires having firm positions on things, and therefore defending those positions and putting money and moral resources behind those positions.

I think humanitarian intervention is a great example. There's this deep antipathy in India towards intervening in other countries, and it's often clothed as “we don't want interventions to turn into regime change.” I think it's something different, which is that India doesn't want to expend blood and treasure and then be criticized for it the way the West is. They like to free ride on the peace and security that the UN Security Council produces, but they don't want to pay the costs of it. That is perhaps one of the impediments to India's path towards great power. At some point India is going to have to shed these old reluctances or old psychological obstacles, and think about what does it mean to be a great power? What does it mean to wield power? Are you willing to wield power in a way that that obviously takes the benefits but also absorbs the costs of wielding power. Everyone's going to dislike you. You can't make anybody happy, but you can be one of the most important countries in the world. That vision of great power status has not yet seeped into Indian foreign policy. It's still very cautious. It's still looking out for India's domestic growth opportunities and strategic autonomy. In a way, it's appropriate. At this stage of India's development, what else do you want to do except to make sure that economic development is on the right trajectory. What India does right now is actually perfectly fine but if you say you want to be a leading power,[10] then you have to act in certain ways. So why do you say that [about great power or leading power ambitions] in the first place? I think India is perfectly positioned to follow a hide and bide strategy like China did in the 90s and 2000s. Say that ‘hey, we will help where we can, but our primary priority is domestic. We have to cater to the prosperity and the growth and the human security of our citizens. That's the number one thing."“ India is perhaps trying to run before it can walk by saying it wants to be a leading power today. In my view, there's a lot more that needs to be done to be that kind of power.

SS: That was going to be my next question. India uses this terminology of ‘vishwaguru’. India’s Prime Minister and Foreign Minister have spoken of India transitioning from becoming a balancing power to an ‘leading power’. India does have a history of helping with global crises and an example that comes to my mind is India’s involvement in the Korean war where India played a role in resolving the crisis in the early years of its independence period, did an able job, but there were issues in the process including differences between India and the United States.[11] We are also reading about potential Indian involvement in the Russia-Ukraine war[12] …

RM: Another example is the IPKF [Indian Peace Keeping Force] intervention in Sri Lanka.[13] That one instance has been so psychologically scarring for the Indian establishment that they never want to get involved in anything else again. At least they haven't until now… And I would say that will be true in the foreseeable future as well. What does it mean to be a great power? It means not learning anything from your mistakes. The U.S. continues to… one would have thought Vietnam would be an epochal lesson for the United States, but yet we had Afghanistan, we had Iraq. It was repeatedly making the same mistakes and not paying much cost in terms of reputation because you're number one, and who else is going to take that spot for now? That mentality has not seeped into the Indian state and maybe it's for the better. Maybe that may come later.

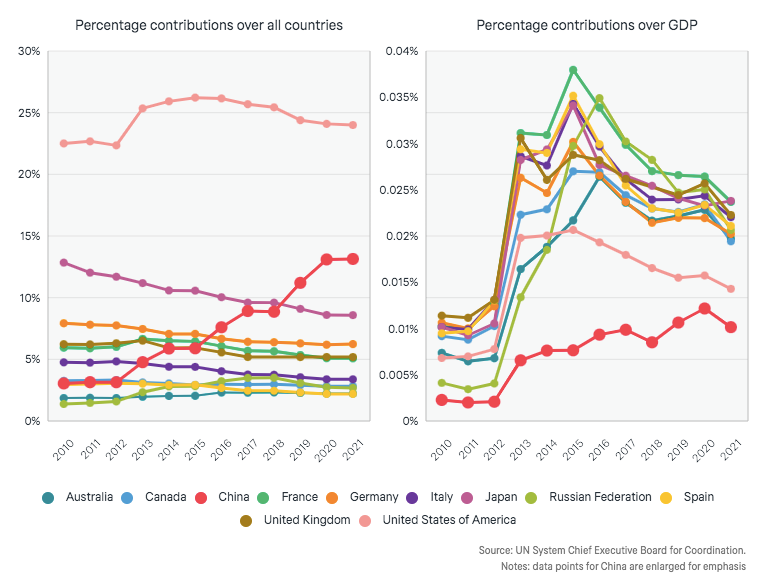

You can almost trace the path that India might take, which may look like what China has done over the last 30 years. China at one point was maybe twice as large as India. Today, it's five times larger than India in terms of economy. This is the moment where China has now really started to make its claim for global leadership. India is not there yet. There is the talk, but there isn't the walk. I think that maybe in the next 20-30 years, we'll see India reaching that point where they're actually willing… the way China today is pushing for the leadership of peacekeeping mandates, shaping mission goals, etc. Not just sending troops, but actually deciding how missions are conducted. That's what China is pushing for. China's goal is for greater represent representation and leadership positions in all across UN bodies,[14] because it has the heft to do that [see Fig. 7]. India is not there yet, and the talk is fine, but I think there is a lot more to do to build up the substance behind it.

SS: In your book Ascending Order, you write about how rising powers care about status and their position in the global hierarchy. You show that rising powers such as China, India, Japan, choose to become a part of the order. You write that “there is no evidence that China and other countries such as India and Brazil are preparing an assault on the international order” [p. 5]. These powers want to be a part of the existing order, reform it, and make sure it is representational and functional. Can you speak a bit about the ‘institutional status theory’? Can you also speak to this subject with its relation to India?

RM: I think it's important to think about all the different ways in which rising powers approach global governance and the international order. There is this flattened view that comes from a dominance of a certain way of thinking about international politics, which is largely Realist, that new powers will automatically challenge the existing order, and existing great powers will automatically push back against them. In fact, there's so much evidence that given the right kind of recognition, new powers can very much become, over time, integrated into ordering the world. They can actually uphold the order. If you look at the speeches that India has made consistently, they are about representation, reform, multilateralism, inclusion, those kinds of things. It’s important to recognize that power transition doesn't inevitably end in conflict. If you think about Graham Allison and the idea of the ‘Thucydides trap,’[15] it's not inevitable, by any stretch. There are also examples of great powers making changes in the order to accommodate new powers. The greatest example is Britain's accommodation of the United States in the late 19th century. That’s what led to a peaceful transition of power between two countries that were actually deeply antagonistic towards each other after the U.S. civil war because Britain helped the Confederacy in that war. So that flattened view of IR [International Relations] is incomplete at best, wrong at worst.

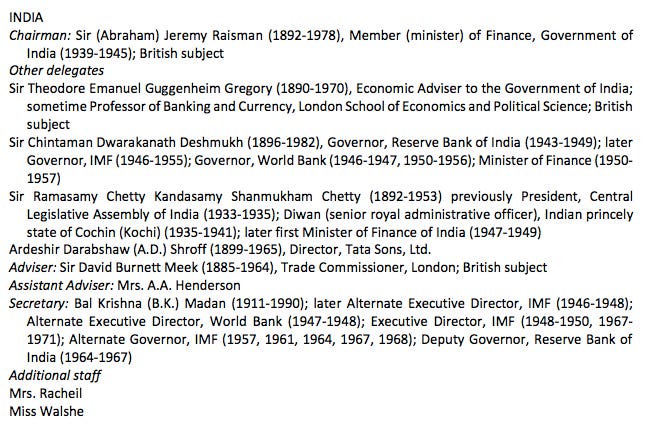

It’s hard to empirically untangle this, because in the contemporary world, if you ask an Indian diplomat, do you care about status, they'll say ‘No, we just care about national interests.’ Actually, if you go back and look at the historical record and how they talked about things and what they actually cared about… In my book, in addition to India in the Cold War, I look at the United States in 19th century, Japan in the early 20th century, China in the last 30 years and today, you see that [these rising powers in these selected time frames] actually, they do talk about these things [i.e. status] to each other, but they wouldn’t admit it if asked point blank. There's a certain socialization that makes us think about diplomacy as realpolitik, as national interests… But ‘national interest’ is a very nebulous and broad term. It can include many things, and I think one of those is due recognition for your rightful place in the international order. I think that much India is now saying publicly, given its role in the First World War, the Second World War, and the making of the [international] order [see Fig. 8 and 9]…

SS: I want to go back to one of your earlier comments on the United States and the bipartisanship over trade policy. Maybe this is an inaccurate historical reading, but time and again we've seen U.S. domestic politics grate against its foreign policy in ways... I’m thinking about the League of Nations, [17] the gold standard,[18] the Rio Agreement[19]. Even now with the rise of China, there’s this sense in the U.S. that the way they’re doing international trade is somehow incorrect. Does this read like U.S. domestic policy clashing against its international efforts? Do we misunderstand how the international order is shaped and the United States’ role in it? If we keep seeing these convulsions between U.S. domestic and foreign policy over a century-long period, what does it say about the international order? Maybe this is too vague a question but I would love to get your thoughts on this...

RM: It's a very good question. Someday, I want to write an article that compares the rise of the United States in the 19th century to the rise of India today. There's a tremendous similarity, because American elites and the public are deeply antithetical to the idea of running the world or going beyond their borders or exercising force abroad, even though they're doing it in all kinds of ways to defend commercial interests. They see themselves as a trading nation that has to protect their trade routes and nothing more. They’re not part of European conflicts. They don't want to be [part of these issues] and yet they are deeply involved in lots of other things. There's a disjunction between the narrative of self and what you actually do. India is very much like that as well. India has interfered in a lot of its neighbouring countries, being involved in their politics, but at the same time, there's this kind of ‘we don't do this’ attitude among Indian policy makers.

You see a change in the U.S. in the late 19th century, when the U.S. first builds a proper navy, and then there are debates about colonizing the Philippines and Hawaii in the late 19th century… There you really start to see the consensus shifting over time. That's when the term isolationism really becomes a thing.[20] It's not in the U.S. vocabulary before that. Isolationism is a word that comes up to criticize people who don't want to go abroad and defend U.S. interests in the Philippines, for example. In some sense, there's always this domestic political battle over the U.S. role in the world and there are ebbs and flows.[21] You have the Spanish-American war, and this period of isolationism, or let's say withdrawal, where they're trying to strike these deals with Japan and Britain through the Washington Naval Treaty… Before that you even have the First World War. So there are these periods of shock, after which the U.S. says ‘we don't want to be involved anymore’. They have the luxury of saying that because they are a continental power, they have water on both sides and relatively weak neighbours to the north and south.

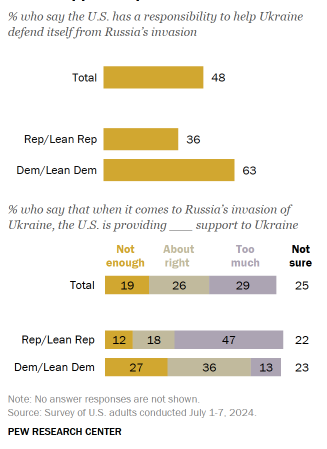

So these ebbs and flows happen, and then the Second World War catapults the U.S. into a position where there's no other choice now, they have to do this [be more engaged with the international order]. So they build this international order with their allies, because they have to essentially bail the Europeans out. The Marshall Plan is a big part of that order. However, the domestic debates never go away. So every time there's this kind of moment of crisis in the international order that drags the U.S. in, those [domestic, isolationist] voices become more prominent. I think 9/11 was one of those moments where what the U.S. was doing was one thing, but then people were saying at home that ‘we've done so much, we've messed up so much in the Middle East,’ and then you get this retrenchment narrative. With the war in Ukraine as well, now you're seeing voices on the Republican side[22] saying that we need to focus on making America great again [Fig. 10].

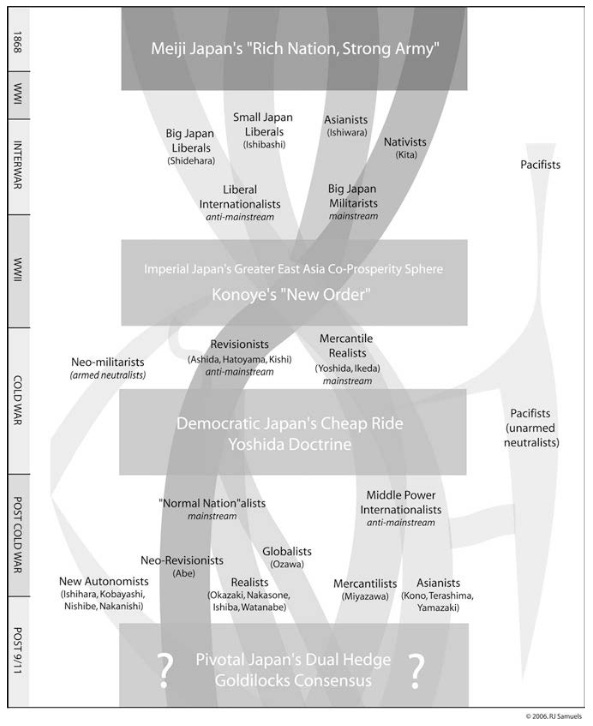

One can read the evolution of international order, at least from the hegemon’s perspective, as a function of domestic debates. They don't always track actual policy. There's conversations about policy, and then there's policy. There are things that the U.S. does because of presidential prerogative that the American public does not even know about until 30 years later when documents are declassified. Also, most voters care about the economy and little else. There is a story to be told here about domestic debates. There's a lovely book by Richard Samuels on Japan called Securing Japan where he maps out different, it’s almost like a tapestry, different strands of political thought in Japan over time [see Fig. 11]. The vertical axis is time, and going from the past to the present, Samuels shows how at different moments, by and large, they disagreed [domestically on what Japan needs to do]. Then there are moments when they converge [domestically] and they agree about something that Japan needs to do, and those are the moments where Japan actually does something in its security or defense policy. It may not be as clean cut as that in the American presidential system, where the President has tremendous authority to make decisions, but it's something like that in the discourse at least.

SS: Just a final question. Actually a two-part question. Firstly, why did you end up thinking about status? What was in your academic journey that prompted you to say status in international order is something that hasn’t been looked at properly and needs to be examined? The second part – what do you think is missing from an Indian perspective about the international order? How can we get a better sense, from India’s view, about what is going on in the international order, and India’s vision for this order and its place in it?

RM: The status stuff is ingrained in the way that those from the non-West see the West once they have experienced the West. Being a student in the UK at a very young age of 16, and having to experience that system, then staying on for college [in the UK], going to the U.S. for further studies and so on, you get a sense of what it means to be excluded or included, what governs that. Then you join the most status-conscious and hierarchical of professions, which is academia. Then you start to see it [the idea of status] even more. The whole notion of tenure is such a hierarchical exercise and this gradation, rankings of universities... Being in academia is a status game. That made me think a lot about status… And, of course in research, you are always told to “find the gap” in the literature. For my intro IR seminar with Andrew Moravcsik at Princeton I read Robert Gilpin’s two books. He has these two books, the red cover – War and Change in World Politics[23] – and the blue cover – The Political Economy of International Relations – and they’re both classics [Fig. 12 & 13]. I read War and Change and that really impacted me. I thought it was incredible. Most modern political scientists wouldn’t think that but that was just what I was drawn to. I wanted to do something in that domain and contribute to that kind of thinking. I started to think about what Gilpin got wrong, and there was a lot. He's a brilliant scholar, but everyone's wrong on some things, and I tried to work on those issues.

That’s on the status thing, both sociological but also intellectual. On what students of Indian IR, or maybe, even Indian diplomats, analysts, scholars might want to look at or should know… I think Indian officialdom has a very good handle on the international order. They understand how it works. They understand their own strengths and their limitations. The IFS [Indian Foreign Service[24]] is a tremendous asset, but I think there there's a certain bureaucratic inertia in the IFS as well. Because you’re stretched so thin,[25] covering so much as India rises, there isn't time to sit and reflect on long-term priorities.[26] So I think a long-term strategic planning kind of office… I know some stuff like that exists in the MEA…

SS: There’s the Policy Planning & Research (PP&R) division[27] in the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA)…

RM: Yeah, something more institutionalized, even at an arm’s length from the institution… Folks are trying to do some of that now. So Rajiv Kumar and Arun Sahgal are undertaking a net assessment in the way that Andrew Marshall[28] was doing in the U.S. There are efforts to do those kinds of things. Going back to the earlier thing I said: if India wants to portray itself as a leading power, a great power, that is deserving of international recognition and leadership, then there has to be thinking about what India's position is on different issues of global importance from vaccine provision to multilateral peacekeeping to climate change. There isn't a sense in which India stakes out that [position and says] “look, this is what we think about these issues.” It's mostly a bit reflexive in terms of criticizing what the West does and then building a policy from that.

Or its policy inaction, masterful inactivity, as they say… And that's worked for India so far. It turns out that not doing anything is actually not a bad strategy when things are going so badly wrong in the world. Whereas the U.S. by trying to do everything, has lost a great deal in some sense. Again, this is a very conditional statement, which is that if you want to be a great power, there are certain things you need to think about. It's perfectly fine to not want to be that [great power]. It's perfectly fine to be a regional power and to attend to the well-being of your citizens. So again, those decisions perhaps need to be thought through a little bit more from a policy perspective.

As far as scholarship goes, if students are thinking about [the international order and India’s place in it]… Maybe thinking more historically would be very, very helpful. I see so much presentism in the way people frame their research questions, the way they think about what is important to study, the number of PhD proposals that now exist on the Quad and AUKUS… Frankly, you can't understand those things until you look back at the history of India's engagement with the world. And why are you so narrowly focused on the security side of things? Of course, at one level, it makes sense, because the funding is in that, but there's a lot more work to be done on India's engagement, for example, with the political economy side. Like IPE (international political economy) studies of India's position, nobody's doing that… I have not seen a single work on India’s approach to IPE from a historical perspective. What was India doing with regard to monetary management or IFIs or development policy at an international scale? [Another example is] foreign aid policy… India was actually giving a substantial amount of its GNI [gross national income] to other countries as a percentage even in the 1960s… India was an aid-giver.. why is that?

I'm a big fan of applied history, which is to think about how the past can inform the present. Using those historical insights to think about the present is very, very important. I am very encouraged [by certain trends in Indian academia]. Pallavi Raghavan, Avinash Paliwal, and I organized a workshop at Ashoka [University] recently [29] and I'm extremely encouraged to see the state of diplomatic studies, which is different from IR, as it is more historical. There's some tremendous work being done, but I do think that there are huge obstacles in the way of young people in India who are working on these issues. When you go to a place like ISA [the International Studies Association, a leading annual academic convention], you're not made to feel like your work is valid, because it's not quantitative, because you are seen as an area studies person and history is not seen as something valuable in IR and political science, you are side-lined. People don't engage with your work, or even worse they are insulting and rude about what you do.

So then you come back demoralized, you think that what you're doing is not worth it and then you lose your confidence to actually contribute something to the literature or to the bank of knowledge that exists out there. Also thinking about building up abilities and confidence within India without necessarily always having to look at the West as an audience… it’s a hard thing to do. The younger generation, the more they plug into U.S. networks, the less content they feel about themselves because the U.S. has a particular way of looking at the world. So it's a paradox, which is that you're building intellectually on the successes of renowned scholars such as Srinath Raghavan and others, going abroad and engaging—and ISA is definitely engaging more now as well, they have travel grants for scholars from the Global South—but when you show up, no one talks to you, no one engages with you, they don't think your work is useful, and therefore it affects your confidence. So there has to be a way to engage with the West without losing your sense of what you're doing as being valuable.

III. Further reading:

I have highlighted some of the resources I referred to prep for the interview, and to provide context and links to some of the points raised in the interview. The sources have been organized thematically, and chronologically.

The international order, the UN & more:

Declaration on the establishment of a ‘New International Economic Order.’ Resolution adopted on May 1, 1974 by the United Nations General Assembly. [May 1, 1974]

H. W. Arndt’s Economic Development: The History of an Idea [1989]

Decision adopted on the ‘Question of equitable representation on and increase in the membership of the Security Council and related matters,’ by the UN General Assembly [October 6, 2008]

Article by Branislav Gosovic and John Gerard Ruggie ‘On the creation of a new international economic order: issue linkage and the Seventh Special Session of the UN General Assembly,’ in International Organization vol. 30, no. 2. [May 22, 2009]

“The Use of the Veto” by Norman Padelford in International Organization 2, no. 2 [May 2009]

“The Legitimacy of the UN Security Council: Evidence from Recent General Assembly Debates,” by Martin Binder and Monika Heupel in International Studies Quarterly 59, no. 2 [June 2015]. The authors find that the UNSC’s “legitimacy deficit results primarily from states’ concerns regarding the body’s procedural shortcomings. Misgivings as regards shortcomings in performance rank second. Whether or not the Council complies with its legal mandate has failed to attract much attention at all.”Report on ‘UN Security Council Enlargement and U.S. Interests’ by Kara C. McDonald and Stewart M. Patrick for the Council on Foreign Relations [December 2010]. Making the case for the UNSC’s enlargement, the authors note that the Council’s permanent membership “excludes major UN funders like Japan and Germany, emerging powers like India and Brazil, and all of Africa and Latin America. Enlargement proponents warn that the UNSC’s global authority will erode if it fails to expand membership from underrepresented regions.”

‘The New International Economic Order: A Reintroduction,’ by Nils Gilman in Humanity: An International Journal of Human Rights, Humanitarianism, and Development vol. 6, no. 1 [Spring 2015]. In the article, Gilman notes that the movement for the NIEO was a “proposal for a radically different future than the one we actually inhabit.” Written in 2015, the article notes that viewed from the current moment, the NIEO “seems like an apparition, an improbable political creature that surfaced out of the economic and geopolitical dislocations and uncertainties of the early to mid-1970s, only to sink away just as quickly.”

‘Two Cheers for the Liberal World Order: The International Order and Rising Powers in a Trumpian World,’ by Rohan Mukherjee in the International Security Studies Forum (ISSF) [February 22, 2019]

Worldmaking after Empire: The Rise and Fall of Self-Determination by Adom Getachew [February 2019]

Notes and press release of the UNGA’s 74th session – ‘Security Council Must Expand, Adapt to Current Realities or Risk Losing Legitimacy, Delegates Tell General Assembly amid Proposals for Reform.’ [November 25, 2019]. At the meeting, India’s representative Syed Akbaruddin stated that it has been “11 years since the start of intergovernmental negotiations — and four decades since inscription of the item on the Assembly’s agenda — making Council reform a Sisyphean struggle.”

‘A Reset of the World Trade Organization’s Appellate Body,’ an article by Jennifer Hillman noting that “The World Trade Organization (WTO) and the rules-based trading system face an existential threat from the Donald J. Trump administration’s blockade on appointments to the WTO’s top court—the Appellate Body. As of December 2019, the Appellate Body had too few members to decide cases, leaving pending appeals in limbo and threatening to turn every future trade dispute into a mini–trade war.” [January 2020]

Chad P. Bown and Soumaya Keynes write on ‘Why did Trump end the WTO’s Appellate Body?’ pointing out that one of the key drivers towards the Trump administration’s approach was tariffs [March 4, 2020]

Article on ‘What’s Happened to the UN Secretary-General’s COVID19 Ceasefire Call?’ by Richard Gowan for the International Crisis Group [June 16, 2020]

Report on ‘The Future We Want: The United Nations We Need’ by the UN for the organization’s 75th anniversary [September 2020]

Global Memo on ‘The UN Turns Seventy-Five. Here’s How to Make it Relevant Again’ by a group of global experts brought under the umbrella ‘Council of Councils’ [September 14, 2020]

UN press release on the ‘Essential Failure of International Cooperation, in Address to Security Council Meeting on Post-Coronavirus Global Governance,’ [September 24, 2020]

A/RES/75/1: Resolution adopted by the General Assembly – Declaration on the commemoration of the seventy-fifth anniversary of the United Nations [September 28, 2020]

‘The New Concert of Powers’ by Richard Haass and Charles Kupchan in Foreign Affairs [March 23, 2021]

Article on ‘The Rise and Fall of Multilateralism’ by Walden Bello in Dissent Magazine [Spring 2021]

‘Our Common Agenda’ report of the UN’s Secretary-General [September 2021]

Ascending Order: Rising Powers and the Politics of Status in International Institutions by Rohan Mukherjee [July 2022]

‘UN Security Council Reform: What the World Thinks’ report edited by Stewart Patrick, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (includes an entry on India by Rohan Mukherjee) [June 28, 2023]. In the introduction, the editor states that “few topics generate so much talk and so little action as Security Council reform. In December 1992, the General Assembly created an open-ended working group to review equitable representation on the council. More than three decades later, that (aptly named) body continues to meet – with no tangible results.”

‘The ABCs of the IFIs: Understanding the World Bank Group Evolution,’ fascinating report by Victoria Dimond and Karen Mathiasen for the Center for Global Development where the authors note, “Shareholders supporting the World Bank’s evolution, included the United States, argue the institution’s country-based approach fails to adequately address shared global challenges. The compounding nature of challenges related to health security, climate, and crises contributing to protracted displacement, is taking a toll on countries and setting back development gains.” [July 2023]

‘It’s time for the United States to end its bipartisan attack on the WTO,’ by Ian Allen in Just Security where he argues that “Biden’s trade team is laudably engaging in multilateral cooperation on WTO progress and reform, but its persistent blockade and lofty prerequisite demands for reviving the dispute system are a detriment to free trade.” [March 4, 2024]

Report on ‘An Evolving BRICS and the Shifting World Order’ by Boston Consulting Group [April 29, 2024]

‘The rise and endurance of mini-laterals in the Indo-Pacific’ by Sarah Teo in the Interpreter [May 2024]

Article on ‘How to Reform the UN without Amending its Charter,’ by Oona Hathaway, Maggie Mills, and Heather Zimmerman for the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace [July 15, 2024]

‘What is the UN’s Summit of the Future?’ by Kate Whiting for the World Economic Forum [July 23, 2024]

‘Planning ahead: 5 things to know about the UN’s landmark Summit of the Future’ by Conor Lennon for UN News [September 3, 2024]

A Q&A on the UN’s Summit of the Future with Nudhara Yusuf, Stimson Center [September 6, 2024]

A backgrounder note on the UNSC by the Council on Foreign Relations [September 9, 2024]

India & the International Order; India & UNSC reforms –

Prime Minister Vajpayee’s statement at the 58th session of the UN General Assembly where he said, “the Iraq issue has inevitably generated a debate on the functioning and the efficacy of the Security Council and of the UN itself. Over the decades, the UN membership has grown enormously. The scope of its activities has expanded greatly, with new specialised agencies and new programmes. But in the political and security dimensions of its activities, the United Nations has not kept pace with the changes in the world. For the Security Council to represent genuine multilateralism in its decisions and actions, its membership must reflect current world realities. Most UN members today recognise the need for an enlarged and restructured Security Council, with more developing countries as permanent and non-permanent members. The permanent members guard their exclusivity. Some states with weak claims want to ensure that others do not enter the Council as permanent members. This combination of complacency and negativism has to be countered with a strong political will. The recent crises warn us that until the UN Security Council is reformed and restructured, its decisions cannot reflect truly the collective will of the community of nations.” [September 25, 2003]

Journal article ‘A New Hope: India, the United Nations and the Making of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights,’ by Manu Bhagavan in Modern Asian Studies where the author notes that “Beginning with the Quit India Resolution, but with antecedents emerging as early as 1919, Nehru set his sights on the distant horizon and allowed himself to dream big. Working with his sister and with Hansa Mehta, Nehru sought to make his hopes a reality through the UN. What he was after was not a modern world of competing sovereign nation-states. Instead, he sought to fashion a new world based on a post-liberal order. In his view, nationality was not pre-determined, and states, correlatively, were not beholden to singularized, essentialized notions of nation.” [June 13, 2008]

Prime Minister Singh’s statement on UNSC reform at the 66th session of the UN General Assembly where he stated “We need a stronger and more effective United Nations. We need a United Nations that is sensitive to the aspirations of everyone - rich or poor, big or small. For this the United Nations and its principal organs, the General Assembly and the Security Council, must be revitalized and reformed. The reform and expansion of the Security Council are essential if it is to reflect contemporary reality. Such an outcome will enhance the Council's credibility and effectiveness in dealing with global issues. Early reform of the Security Council must be pursued with renewed vigour and urgently enacted.” [September 2011]

Article on ‘India and the UN Security Council: An Ambiguous Tale,’ by Rohan Mukherjee and David M. Malone in Economic and Political Weekly [July 2013]

The UN chronicle has an essay by Muchkund Dubey (former Foreign Secretary of India who was present during the creation of the G77] where he writes on the history and importance of the G77 [May 2014]

Policy brief on ‘India and the International Order,’ by Bruce Jones for the Brookings Institution where he notes that India’s “status as an emerging global power is not just being recognized but also increasingly institutionalized, with a seat on the G20, the initial presidency of the BRICS Development Bank, and more. As the country continues to assert itself economically on the world stage, India will inevitably wield greater international political and, possibly, military influence.” [August 27, 2014]

IISS Lecture by Dr. Jaishankar (former Foreign Secretary, current Foreign Minister) where he argued that “In so far as larger international politics is concerned, India welcomes the growing reality of a multi-polar world, as it does, of a multi-polar Asia. We, therefore, want to build our bilateral relationships with all major players, confident that progress in one account opens up possibilities in others.” [July 20, 2015]

Paper on ‘India as a Leading Power,’ by Ashley Tellis at the Carnegie Endowment for International Affairs [April 4, 2016]

Journal article on ‘India and the International Order: Accommodation and Adjustment,’ by Deepa M. Ollapally in Ethics and International Affairs where the author argues that “India's deep-seated anti-colonial nationalism and commitment to strategic autonomy continues to form the core of Indian identity” which makes “India's commitment to Western-dominated multilateral institutions and Western norms, such as humanitarian intervention, partial and instrumental.” [March 7, 2018]

‘Present at the Creation: India, the Global Economy, and the Bretton Woods Conference,’ journal article by Srinath Raghavan and Aditya Balasubramanian in Journal of World History (see footnote #16) [March 2018]

Remarks by India’s Foreign Minister, Dr. Jaishankar, at the Russia-India-China Trilateral Foreign Ministers’ meeting where he stated, “international affairs must also come to terms with contemporary reality. The United Nations began with 50 members; today it has 193. Surely, its decision making cannot continue to be in denial of this fact. We, the RIC countries, have been active participants in shaping the global agenda. It is India’s hope that we will also now converge on the value of reformed multilateralism.” [June 23, 2020]

Article on ‘India and the United Nations: Past and Future,’ by Vijay K. Nambiar (former Deputy NSA and India’s Permanent Advisor to the UN) who notes that “if the multilateral system embodied in the institutions of the UN is to retain its legitimacy, effectiveness and credibility in our changing world, a reform of its ‘basic structure’ is badly needed to prevent it even after its seven decades long existence and utility to go the way of the League of Nations. While we can scarcely disregard the reality of an incipient bipolarisation of the world’s power structure considering the positions of the US and China (the UN often obsesses over it), what we need to consider is for the UN to respond to the imperative of a broader multi-polarity involving medium ranking powers, more regularly and providing them more institutional space. A restructuring of the UN Security Council is thus absolutely essential.” [July-September 2022]

Article on ‘China and India weren’t critical of Putin’s war. Did that change?’ by Rohan Mukherjee in the Washington Post, where he notes that “History shows, however, that rising powers like China and India do not simply value economic and security goals. They also value being recognized as eminent countries with an elevated status in international politics… China and India today are looking for opportunities for leadership in a global order dominated by the U.S. and its allies. New Delhi, for example, seeks a permanent seat on the U.N. Security Council. India’s foreign minister declared in 2020 that India deserved “due recognition” for its contributions to global order and called for “reformed multilateralism.” [September 26, 2022]

Journal article ‘What is a vishwaguru? Indian civilizational pedagogy as a transformative global imperative,’ by Kate Sullivan de Estrada in International Affairs [March 2023]

Journal article on ‘The world Delhi wants: official Indian conceptions of international order, c. 1998–2023,’ by Atul Mishra in International Affairs [July 2023]

Article on ‘Is India the World’s Next Great Economic Power?’ by Bhaskar Chakravorti and Gaurav Dalmia in the Harvard Business Review [September 6, 2023]

Article in The Hindu on India’s detailed model on UNSC reform on behalf of the G4 nations [March 8, 2024]

Article on ‘Great power ambitions: India’s aim at the UN Security Council’ by Arkoprabho Hazra in The Interpreter [March 13, 2024]

An overview of India’s historical relationship with various United Nations bodies by the Ministry of External Affairs

[1] Described as the “most widely discussed transnational governance reform initiative of the 1970s,” the NIEO’s fundamental objective was to work towards the establishment of an economic order based on “equity, sovereign equality, interdependence, common interest and cooperation among all States, irrespective of their economic and social systems which shall correct inequalities and redress existing injustices” making it “possible to eliminate the widening gap between the developed and developing countries and ensure steadily accelerating economic and social development and peace and justice for present and future generations.” Writing about the NIEO in 2015, Nils Gilman, wrote that the NIEO “seems like an apparition, an improbable political creature that surfaced out of the economic and geopolitical dislocations and uncertainties of the early to mid-1970s, only to sink away just as quickly.”

[2] Group of 77 (or G77) was formed on June 15, 1964 following the conclusion of the first United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) emerging as “the most importance forum of the developing countries for harmonizing their views on global economic issues, evolving common positions on these issues, and advancing new ideas and strategies for negotiations with developed countries.”

[3] Then UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan said the US-led war on Iraq was “not sanctioned by the UN security council or in accordance with the UN’s founding charter” and was “illegal.” Also see this UN press release (from March 26, 2003) on the first debate the UNSC held on Iraq where a majority of the speakers “called on to end the illegal aggression and demand the immediate withdrawal of invading forces.”

[4] The SCO was established on June 15, 2001 in Shanghai by Kazakhstan, China, Kyrgyz Republic, Russia, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. Current members of the SCO also include India, Iran, and Pakistan.

[5] AIIB, formed in 2016, is a multilateral development bank with a capitalization of USD 100 billion. The bank was established with 57 founding members and has since grown to over 100 approved members. As one scholar argues, one of the reasons behind the creation of AIIB Was Beijing’s “concern that the governance structure of existing International Financial Institutions (IFIs) was evolving too slowly.”

[6] BRICS (see the following footnote) established the New Development Bank (NDB) in 2015 to mobilize “resources for infrastructure and sustainable development projects in emerging markets and developing countries (EMDCs).” A scholar notes that the NDB represents the BRICS’ “pivot to action after long-pending IMF and World Bank reforms failed to materialize between 2010 and 2015,” and the bank is fully operational with each of the 5 states contributing “an equal share of the $50 billion initially subscribed capital, and each has an equal voice.” In 2021, the NBD Board of Governors “approved the admission of Bangladesh, UAE, Egypt and Uruguay into [the] NBD family, which heralded the beginning of the Bank’s expansion as a global multilateral institution.”

[7] BRIC, a group of major emerging economies, Brazil, Russia, India and China, was a term coined in a 2001 Goldman Sachs Economic Research report authored by then head of Global Economic Research Jim O’Neill who projected that over the upcoming decade, the weight of these four nations in world GDP would grow significantly and recommended that “the G7 should be adjusted to incorporate BRIC representatives.” Heads of the group met at the margins of the 2008 G8 meeting in St. Petersburg leading to the first ‘BRICs’ summit in 2009. In 2010, at a foreign minister’s meeting, the group invited South Africa. Leaders from the five nations met for the first time in 2011. A (western) media article from the time notes that the BRICS was “no longer an artificial body founded on comparable economic performance, but increasingly a political club representing the developing world, determined to counterbalance western influence in major international forums.” Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) were invited to join the group “with effect from 1 January 2024,” - Argentina was invited as well, but President Javier Milei pulled out in December 2023, shortly after taking office. Reportedly, over 40 countries have expressed interest in joining the group, and is viewed by many as an “alternative to global bodies viewed as dominated by the traditional Western powers.”

[8] In an influential report on ‘Making U.S. Foreign Policy Work Better for the Middle Class,’ Dr. Tellis (along with co-authors) noted that the “Trump administration has upended a decades-long approach to U.S. international trade policy.” The authors of this report (that informed the Biden administration’s approach on foreign and domestic policy in parts) recommend that the U.S. “should use its tremendous wealth and power to shape a global economic recovery that will help advance middle-class well-being.” How do you go about doing this? One way is to “revamp the U.S. international trade agenda to level the playing field with other countries while pursuing domestic policies that advance more inclusive economic growth.”

[9] In 2017, the U.S. government “unilaterally hamstrung the WTO’s binding dispute system by blocking appointments to its highest “court,” the Appellate Body. By December 2019, the body dropped below its three-person quorum, which effectively means it cannot hear appeals. Today, all seven Appellate Body seats are empty.” Writing about some reform initiatives under President Biden, an article in Politico noted that Biden has “held” course that President Trump’s administration embarked on, reflecting “bipartisan abhorrence in Washington at the WTO’s perceived overreach.”

[10] In a 2015 speech, then Foreign Secretary (and current Foreign Minister) S. Jaishankar highlighted a “transition” in India’s foreign policy under Prime Minister Modi and said that India’s aspires “to be a leading power, rather than just a balancing power.” Months before, PM Modi made a similar call. Speaking to the heads of Indian missions across the globe, the Prime Minister urged diplomats to “help India position itself in a leading role, rather than just a balancing force, globally.” Ashley Tellis wrote on the subject here.

[11] Chapter 3 of Rudra Chaudhuri’s Forged in Crisis: India and the United States since 1947 outlines the critical role India played in ending hostilities to the Korean War. While the United States and India had substantial differences when it came to the war, Chaudhuri shows how key U.S. officials (irritated with India’s policy of non-alignment) “came to respect” the “contribution India made to ending the war on the Korean Peninsula” [p. 255]. There were ongoing differences between India and the United States, including over the recognition of the PRC, which India had recognized in 1949 but the United States “refused to recognize or admit to the UN Security Council” at the time [p. 50]. As a media report on India’s involvement notes, “India’s Permanent Representative to the UN and a member of the UN’s Special Political Committee, V.K. Krishna Menon took on the responsibility of finding a solution to the pressing issue of the future of the prisoners of war,” and following month of failed deliberations, India proposed the “creation of a Neutral Nations Repatriation Commission (NNRC) to facilitate the repatriation of prisoners.” The NNRC was subsequently set up, with India at the helm.

[12] Writing about India’s role in the Russia-Ukraine war, Suhasini Haidar points out all the speculation over India’s “determination to help resolve the war has gained traction” as PM Modi recently visited both Moscow and Kyiv, and there are potential leader level meetings planned with Ukrainian President Zelenskyy at the UN this week, and with Russian President Putin at the BRICS Summit in October [Ms. Haidar wrote this piece on Sept. 20, 2024; PM Modi met President Zelenskyy on Sept. 23, 2024]. Haidar also notes that “in his third term, Mr. Modi would no doubt like to build a global legacy, much like India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru was able to do by mediating between the USSR and Austria for the withdrawal of Soviet troops in exchange for a policy of neutrality, or by India leading international efforts and UN commissions on wars in Korea, Vietnam and Cambodia” highlighting India’s history on this matter.

[13] Chapter 4 of Amb. Shivshankar Menon’s Choices: Inside the Making of India’s Foreign Policy has a helpful overview of India’s interventions in Sri Lanka. He notes that Sri Lankan independence in 1948 brought about a change in the socio-political setup with the minority Sri Lankan Tamil community that was “accustomed to thinking of itself as a natural ruling elite” [p. 84] seeing itself sidelined. As the situation deteriorated over decades, the Indian and Sri Lankan side came to an understanding in 1987 whereby India dispatched the IPKF to “accept the surrender of arms by Tamil militants as part of a general cease-fire” [p. 88]. Amb. Menon notes that “it is hard to see the Indian intervention in Sri Lanka in the late 1980s as anything but an inexorable tragedy” and there were no good choices as “sharpening ethnic conflict fueled the rise of terrorism within the Tamil community, led to the flow of Tamil refugees into India, and even saw fighting among Sri Lankan Tamil militant groups on Indian soil” [p. 88-9]. He further notes that “the bitterness left by the Indian intervention had long-lasting effects” [p. 89] with then Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi being assassinated by a female LTTE suicide bomber in 1991.

[14] Writing about China’s involvement in the UN, scholars at the United States Institute of Peace note that after the UN switched recognition from Taiwan to the People’s Republic of China in 1971, Beijing “invested heavily in U.N. diplomacy, seeking to expand its influence in the international body through financial support, staffing, aligning votes and shaping U.N. language.”

[15] In an influential 2015 Atlantic essay Graham Allison opined that the Greek historian Thucydides’ insights (on Athens’ rise and the fear that this instilled in Sparta leading to war) can help one understand the contemporary nature of U.S.-China tensions and what China’s rise means for the United States. In his 2017 book Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’ Trap? Allison argues that “as far ahead as the eye can see, the defining question about global order is whether China and the US can escape Thucydides’ trap” [Introduction].

[16] Aditya Balasubramanian and Srinath Raghavan note that “India’s mere presence at Bretton Woods reminds us of the fact that it was an inclusive affair” but highlight that “India’s inability to inscribe its core concerns on the conference’s proceedings points to the inbuilt hierarchies of power in the “liberal international order” being inaugurated at Bretton Woods” [p. 66-7] in their article “Present at the Creation: India, the Global Economy, and the Bretton Woods Conference.” The article starts with a note on how A. D. Shroff (see Fig. 9) was upset on his return from the conference because the Indian delegation had “failed to make headway in resolving the crucial sterling balances question. Built up over the past five years in exchange for financing Britain’s war in Asia, India’s sterling balances now amounted to almost £1.3 billion. They had transformed the longstanding Indo-British economic relationship: from perennial debtor, India emerged as one of the largest creditors to its imperial master” [p. 65].

[17] The League of Nations was first proposed by U.S. President Woodrow Wilson and the Covenant of the League (its charter) was attached to the Treaty of Versailles. An archival entry by the State Department notes that the “struggle to ratify the Treaty of Versailles and the Covenant in the U.S. Congress helped define the most important political division over the role of the United States in the world for a generation.” The United States never joined the League.

[18] At the end of WWII, there “was literally no functioning global economy, so nations got together to create a new trading system and a new monetary system.” The United Nations ‘Monetary and Financial Conference’ was organized in July 1944 in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire [hence the name, ‘Bretton Woods agreement’] where the delegates agreed to create two new institutions, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (now the World Bank Group), and one of the key elements of the agreement was to peg to the dollar to the gold (at $35 an ounce). After decades of surplus U.S. dollars (due to “foreign aid, military spending, and foreign investment”) threated the Bretton Woods system per the U.S., and there were concerns that a “run on the dollar” accompanied by “mounting evidence that the overvalued dollar was undermining the nation’s foreign trading position.” President Richard Nixon and his top economic advisors gathered at Camp David in August 1971 to tackle this issue, and on August 15, Nixon announced a ‘New Economic Policy’ that would “create a new prosperity without war” (dubbed colloquially as the ‘Nixon shock’). Among the measures that Nixon took was to suspend the dollar’s gold convertibility which was intended “to induce the United States’ major trading partners to adjust the value of their currencies upward and the level of their trade barriers downward so as to allow for more imports from the United States.” A State Department archival history account notes that while Nixon’s announcement was “a success at home” it “shocked many abroad, who saw it as an act of worrisome unilateralism.” Notably, none of the folks with President Nixon at the Camp David meetings had a foreign policy minded-focus (save for Nixon, a ‘foreign policy president’). A scholar on the subject has argued that Nixon’s 1971 speech had “enormous approval” and had the “effect that Nixon wanted” as he was “seen to have grabbed control of a situation that had been deteriorating – namely, increasing inflation and growing trade imbalance” and points to the decision that was taken keeping in mind domestic constituencies but that had global consequences. Another scholar states that the ‘Nixon shock’ was “much more about domestic politics.”

[19] This media report highlights that the United States “championed the idea of a biodiversity treaty” throughout the 1980s but following successful negotiations at the Rio de Janeiro Earth Summit, then-president George H. W. Bush “refused to sign [the treaty that resulted from the 1992 Earth Summit] amid the tumultuous presidential election.” It also points out that “when Bill Clinton took office in 1993, he did provide his signature, but the agreement failed to get Senate approval.” The United States has “one of the worst records of any country in ratifying human rights and environmental treaties,” partly due to the design of its political system, but also because it “shuns treaties that appear to subordinate its governing authority to that of an international body like the United Nations.”

[20] The Office of the Historian within the U.S. State Department notes the following about U.S. isolationism in the 1930s, “During the 1930s, the combination of the Great Depression and the memory of tragic losses in World War I contributed to pushing American public opinion and policy toward isolationism. Isolationists advocated non-involvement in European and Asian conflicts and non-entanglement in international politics.” Another note by the same office argues that “Although clear dangers emerged during the Great Depression of the 1930s, the massive economic shocks reinforced the country's isolationist inclinations during the rise of totalitarianism,” stating that the State Department “returned to the passivity of the 19th century, and accepted a secondary role from 1919-1939.”

[21] In ‘Internationalism/Isolationism: Concepts of American Global Power’ Stephen Wertheim examines the conceptual history of “isolationism” in the United States and recounts “how the internationalism/isolationism dualism was fashioned in the 1930s and early 1940s” [p. 54]. In ‘The Myth of American Isolationism,’ Bear Braumoeller argues that “the characterization of America as isolationist in the interwar period is simply wrong. The United States in the 1920s and 1930s was not uninvolved in European politics, nor were its citizens unconditionally opposed to involvement in European security affairs” [p. 4].

[22] From a February 2024 Associated Press article on the issue: “the GOP’s ambivalence on Russia has stalled additional aid to Ukraine at a pivotal time in the war… Many Republicans are openly frustrated that their colleagues don’t see the benefits of helping Ukraine… Within the Republican Party, skeptics of confronting Russia seem to be gaining ground… Even before Trump, Republican voters were signaling discontent with overseas conflicts, said Douglas Kriner, a political scientist at Cornell University.”

[23] The motivating question for Gilpin in this book is – “How and under what circumstances does change take place at the level of international politics?” and crucially, “are answers that are derived from examination of the past valid for the contemporary world?” [p. 2]. The author argues that an “international system is established for the same reason that any social or political system is created; actors enter social relations and create social structures in order to advance particular sets of political, economic, or other types of interests” [p. 9]. Furthermore, the interests of individual states within this international system change due to “economic, technological, and other developments” [p. 9]. With these changes, “those actors who benefit most from a change in the social system and who gain the power to effect such change will seek to alter the system in ways that favor their interests” [p. 9]. As Rohan Mukherjee previously explained, and argues in his book, his thesis on the role that rising powers play in the international system is at odds with Gilpin’s formulation.

[24] In September 1946, before India’s independence in 1947, the Government of India created a “service called the Indian Foreign Service for India’s diplomatic, consular and commercial representation overseas.”