After the Modi-Trump meeting: What next for India-U.S. ties? (Part I)

Notes on the February 2025 Modi-Trump bilateral meeting, analyses of the India-US relationship, and issues on the trade front

On February 13, 2025, U.S. President Trump hosted India’s Prime Minister Modi for their first meeting since Trump’s return to the White House on January 20, 2025.

In this post, I will analyze some of the announced measures, highlight analyses of the bilateral meeting, and chalk out some trends I’ll watch for as the India-U.S. relationship evolves under Trump 2.0. This is Part I of a series of analyses on the future of this relationship, and it focuses on the trade relationship (see section III). Subsequent editions in this series will explore defense & security ties, energy ties, and the US and India’s differing views on the international order. Note: I have highlighted text throughout this post for emphasis.

ICYMI: I had a wide-ranging conversation on how the United States’ relationship with India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and other subcontinental actors might play out under the second Trump administration with Daniel Markey and Elizabeth Threlkeld. You can read it here.

If you find any value in this post, please do share it with your friends and colleagues.

I. The Modi-Trump meeting:

PM Modi was the fourth state leader to visit Pres. Trump since the latter’s re-election and the two sides announced several initiatives. Several reports read into the timing of PM Modi’s visit, with the US-India Strategic Partnership Forum noting that the Indian PM being the fourth head of state to meet with Trump showcased the “importance and heft of the bilateral relationship.”

In a conversation with Karan Thapar, Daniel Markey pointed out that this meeting,

“[C]ame about mainly from the Indian side in a desire from PM Modi and his team to get in quickly, to see President Trump and to make sure they [the Indian side] could get a word with him and to try to influence him with the understanding that a kind of offense… early on charm offensive so to speak would probably be a good defense… [This came] out of the concern that Washington might be tougher on India now under Trump than they were under the Biden administration… This [meeting] is largely coming at the request of the Indian side. From Washington though, I think there is an eagerness to demonstrate that Trump routinely and regularly sees the leaders of major powers around the world and he is eager to have them come visit.” [3:15-4:15 mins]

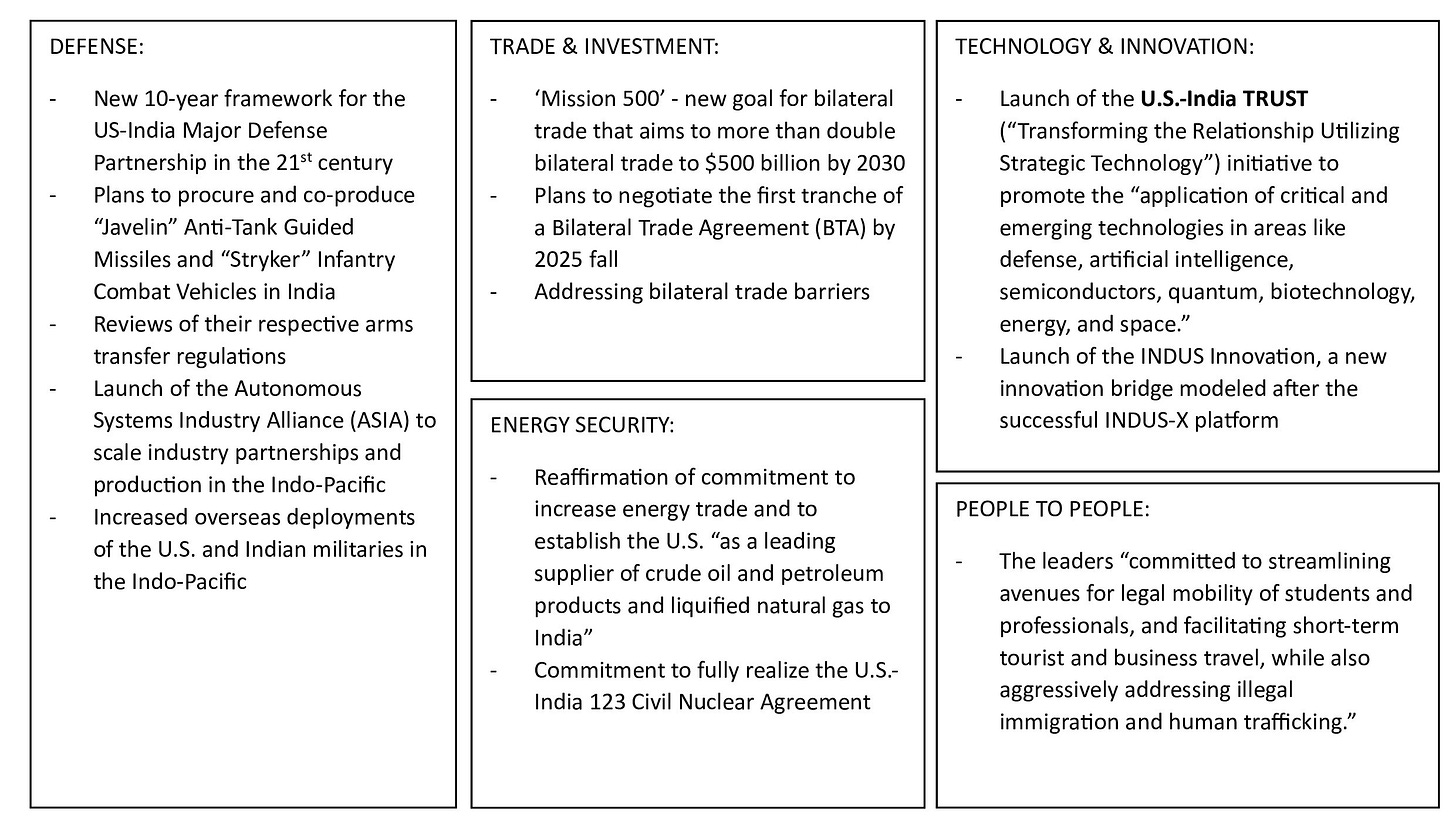

That the meeting came about at the Indian side’s request arguably doesn’t matter much in the long term, especially if the aim was to get in a word early. C. Raja Mohan said as much, writing that “sending the political and geopolitical earthquakes in Washington, New Delhi pushed for an early Modi-Trump meeting that could impart stability to India’s most important relationship.” Some of the key outcomes from the meeting include the following (see Fig. 1).

II. Analyses of the meeting:

On Defense -

Devirupa Mitra at The Wire has one of the most comprehensive reports of the bilateral meeting, writing -

“Trump also said that India would be increasing its purchases for US weapons this year by “billions of dollars”. “We’re also paving the way to ultimately provide India with the F-35 stealth fighters,” he added. The Indian side, however, downplayed the offer, saying it was too early to decide as the acquisition process had yet to begin. “On military sales to India, look there is a process by which platforms are acquired…There is, in most cases, a request for proposals that is floated. There are responses to those. They are evaluated. I don’t think with regard to the acquisition of an advanced aviation platform by India, that process has started as yet. So this is currently something that’s at the stage of a proposal. But I don’t think the formal process in this regard has started as yet,” said foreign secretary Vikram Misri. Since 2008, India has procured more than $20 billion worth of US weapon systems.”

On the subject of F-35 stealth fighter sales to India, Seema Sirohi, in the Economic Times writes,

“As for Trump's offer to sell F-35 stealth fighters, it's unlikely to go far. F-35s are hugely expensive and considered 'a system of systems' requiring a whole range of accoutrements to be truly effective. A policy review is promised. But US officials will likely determine that F-35 could be 'compromised' by Russian S-400s present in India. If at all an offer comes, it will have such onerous conditions as to be meaningless. That said, Trump's willingness to sell India the top fighter is still significant. Recall that he went against existing US policy in his first term to allow the sale of armed drones (MQ-9B Predators) to India paving the way for Biden to sign the deal.”

Writing in The Print, Rajesh Rajagopalan notes that "there is little to suggest any progress on US-India ties” following the bilateral meeting. On initiatives such as COMPACT [Catalyzing Opportunities for Military Partnership, Accelerated Commerce & Technology], TRUST, and ASIA (see above), he adds,

“What we see is the favourite effort of both leaders in renaming previous agreements and coming up with cute acronyms that cannot paint over the reality that the relationship has more or less plateaued, with few ideas on how to move it forward. All we have are the various initiatives that bureaucracies come up with to add to the word length of the necessary joint communique.”

On the matter of tech transfers between India and the U.S., Rajagopalan writes,

“How would bits of US technology handed to some Indian public-sector or research and development entities actually benefit India to develop its technological capacity? No matter—India kept harping on technology transfers. It was always highly unlikely both because India can offer little in return and because Trump is now focused more on other issues such as getting better trade numbers than on the strategic challenges facing the US.”

Ravi G. Kapoor, the former Deputy Commander-in-Chief of the Strategic Forces Command argues in NatStrat,

“A logical follow up of the SOSA [Security of Supplies Arrangement; this allows both states to “request each other for priority delivery of certain defense items”] is the Reciprocal Defense Procurement Agreement (RDP). The RDP is a more formal and legally binding agreement that mandates prioritization of defense orders, paving the way for more extensive joint production and technological collaboration.”

On India buying defense goods worth “billions of dollars,” Prashant Jha writes,

“Trump’s reference to “billions of dollars” of sales is serious. The fact that Trump cleared the Predator drones but India took seven years to buy the drones (under the next presidency) is something that his ecosystem remembers. His team also knows how Trump forced India to speed up the acquisition of Apache attack helicopters and SeaHawk helicopters, by threatening to announce it in Ahmedabad unilaterally and making the success of his 2020 visit contingent on it. This time, Trump wants to sell more systems and quickly.”

Harsh V. Pant and Kartik Bommakanti underline challenges to the bilateral defense relationship,

“One of the critical elements missing in the joint statement was virtually no mention of the urgent delivery of General Electric (GE) Aerospace’s F-404 GE-IN-20 engines for the India-made Tejas-Mark 1A fighter aircraft or the delivery and eventual 80% Transfer of Technology (ToT) to India’s Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL) for the more advanced GE engine F-414 to power the Mark-II variant of the Tejas. Second, Mr. Trump, in the joint press conference with Mr. Modi, did reiterate (as the joint statement suggests) the possibility of New Delhi purchasing the F-35 Lightning II fighter aircraft. Integrating the F-35 would be the most difficult to pull off as the Indian Air Force (IAF) has too many persistent gaps, which it is struggling to fill… The absence of any word in the joint statement on GE’s engine supply for the Tejas is cause for concern due to the dwindling number of IAF fighter squadrons, which could fall to under 30… Integrating the F-35 into the IAF is likely to be demanding as it already fields very diverse aircraft, which might leave it incurring fairly substantial infrastructure and maintenance costs as well as a highly intrusive on-site inspection U.S. regime.”

On Trade and Investment -

Akshay Sinha in the Indian Express -

The Indian government “has read the writing on the wall and is taking prompt steps to pacify Trump on trade. The most recent round of tariffs cuts in the latest budget directly speak to many of Trump’s grievances, such as high tariffs for Harley-Davidson motorcycles. Reports indicate that there may be other offerings during the meetings now.”

Sinha also recommends a “sectoral FTA” [Free Trade Agreement] as a full trade agreement is unlikely and politically difficult given “India’s sensitivity to agriculture.” He argues,

“Notably, the Trump administration has already indicated a willingness to negotiate sectoral trade agreements. Trump’s “America First Trade Policy Memo” of January 20 explicitly mentions this approach. Trump has also previously pursued such deals, such as an agreement with Japan during his first term, thus setting a precedent.”

C. Raja Mohan in the Indian Express -

“On the contentious issue of trade and tariffs, Modi and Trump decided to take a positive approach and set themselves an ambitious annual bilateral trade target of $500 billion. They also gave themselves time to negotiate a bilateral trade deal by this autumn, when Trump is expected to visit Delhi. The two sides do have a negotiating record in Trump’s first term (2017-21) and it should be easy to pick up those threads and have a reasonable agreement ready by the time Trump arrives later this year.”

Prashant Jha raised some of the challenges the Indian govt. will face as it deals with prickly trade issues in the Hindustan Times,

“The first test for the economic establishment involves working with Trump’s team to arrive at the first tranche of a bilateral trade agreement (BTA). Don’t assume this is just about reducing tariffs, which in itself will be a challenge given political sensitivities. And don’t assume that buying more energy by itself will make Trump happy. Trump’s order on reciprocal taxes factors in the entire menu of policies that can be seen as favouring domestic businesses over foreign businesses (subsidies, tax regimes, regulatory actions). The United States has its eyes on India’s data rules, treatment of American e-commerce and tech companies, and any non-tariff barrier that can be remotely interpreted as distorting a “level playing field”.”

On Energy Security -

Shayak Sengupta and Rama T. Ponangi have an excellent briefer on India-U.S. energy ties for the Center on Global Energy Policy, where they also outline some of the limits to India’s purchases of US oil and gas,

“First, while Indian state-owned enterprises can directly buy energy on behalf of the government of India, the fossil fuel trade between the two countries is largely market driven. Short of drastic actions (e.g., sanctions), neither government has extensive influence on these market dynamics. Second, there are public finance consequences for India. Importers like India are subject to the vagaries of global prices. Buying more expensive oil and gas to bring geopolitical goodwill may inefficiently allocate public capital and deplete foreign exchange for the country… Lastly, increasing India’s purchases of US oil and gas for geopolitical aims constrains the country’s own energy security and import choices. Since 2022, India has taken advantage of discounted Russian oil imports, but recent tighter US sanctions will likely dampen future imports.”

A Financial Times article by Andres Schipani and Jamie Smyth stated,

“At the moment, Russia is the main supplier of crude to India, while Qatar is the biggest provider of liquefied natural gas. The US is the world’s largest LNG exporter, and already accounted for about a fifth of India’s supplies in 2024… “Gas will be the real deal. India is one of the last untapped markets for gas globally which has scale,” said Rajeev Lala, director of upstream solutions at S&P Global. At a time of more benign prices for US gas exports, “we are ready to take more natural gas”, said Arvinder Singh Sahney, chair of the Indian Oil Corporation, one of India’s top importers… The US LNG industry said it stood ready to boost exports to India, citing private operators’ aggressive growth plans for the construction of new terminals.”

Sanjeev Choudhary reports on some of the limitations in India-US energy ties in the Economic Times,

At the Modi-Trump joint address, “Trump said the trade imbalance between the two countries could be addressed “very easily” by selling more US oil and gas to India… India’s state-run companies will be under pressure now to look for opportunities to buy more US oil and gas, which aren’t always competitive due to higher freight… State-run GAIL already has a long-term LNG import deal from the US. Indian Oil, GAIL and BPCL are in talks for long-term US LNG deals, [Petroleum and Natural Gas secretary Pankaj] Jain said. Some Indian gas companies are, however, against stitching US LNG deals as they are linked to gas benchmark Henry Hub. They prefer crude-linked LNG contracts since the crude market is considered more global and stable.”

Following the meeting, a senior official with an Indian refiner told the Indian Express,

“If US crude is priced competitively compared to oil from other suppliers and fits well in our product slate profile and other technical parameters, we can certainly buy more. The bottomline is that all our crude purchases are dictated by commercial considerations including price and quality.”

On the International Order -

In an episode of The President’s Inbox, Tanvi Madan voices the impact of Trump’s talk of a rapprochement with Russia and China, noting that,

“Trump’s unpredictable stance on China, oscillating between tough rhetoric and conciliatory overtures, has raised alarm in New Delhi. Similarly, any U.S.-Russia détente could ease economic pressure and undermine India’s balancing strategy. Even while pushing for deeper U.S. partnership, expect Modi to look to strengthen India’s autonomy and self-sufficiency to hedge against being excluded from great power politics.”

Dhruva Jaishankar highlighted the continuation of key multilateral engagements,

India and the United States “agreed to continue — and even build upon — various forms of institutional engagement between their two governments. These included continued cooperation in Quad, I2U2, and the India-Middle East-Europe Corridor (IMEC). They also hinted at more minilateral initiatives, which suggests the Trump administration may be less sceptical of multilateral efforts than many of its critics feared.”

Asfandyar Mir from the United States Institute of Peace argues that,

“Trump’s perspective on India's role regarding China suggests a distinct approach to geopolitics that goes beyond traditional balance of power considerations without dismissing them. India’s value as a critical player in the Indo-Pacific region and counterweight to China remains important, but Trump appears to see India as a standalone, vital power in Asia and the globe, with whom the United States needs a strong, sustainable partnership anchored in equitable distribution of benefits, particularly economic ones… To be sure, this view also leaves space for balance of power cooperation and encourages investment in capacities of both countries to act collectively across strategic domains — but it seeks to lower the burden America must shoulder in bilateral ties.”

Rohan Venkat, in his ‘India Inside Out’ newsletter, examines what the Trump administration’s embrace of multipolarity means for India,

“[W]ill the US embrace of a multipolar world – taking place before India’s geo-economic heft is sufficient for it to assert itself as a global, or even Asian, pole – actually end up harming India’s multi-alignment strategy? Will India receive net benefits from a tighter American embrace, even a more extractive one, or will it hand over too much of its autonomy to DC?… the US president’s consistent indications that he is willing to work with China are certainly inspiring some concern, even if a Sino-American deal seems unlikely and Modi doesn’t have very many options in the short-run. But Ukraine’s fate is inspiring commentary about what it means to be associated with a great power and then cast aside, and whether India has the werewithal to continue pursuing multi-alignment.”

III. What next for India-U.S. trade ties?

That PM Modi got an early word in following Trump’s re-election, India’s External Affairs Minister got a prime seat at the inauguration [see Fig. 2; as Rajesh Rajagopalan noted in a conversation with Milan Vaishnav, these things are heavily choreographed], a QUAD meeting was scheduled on January 22, 2025 (a day after the inauguration) and the Modi-Trump bilateral meeting happened within a month of the latter’s return to power point to the current U.S. administration’s continued, deep interest in the India-U.S. relationship.

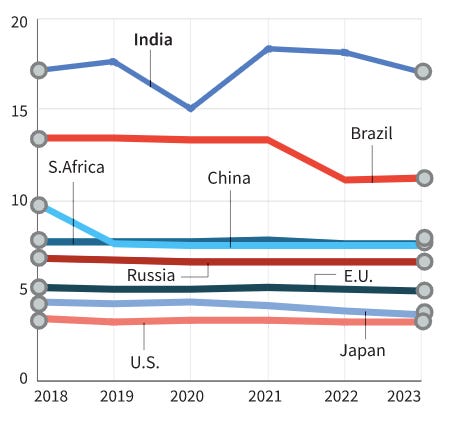

The question is: How will this relationship evolve under Trump 2.0? As I noted in the interview with Dan Markey and Elizabeth Threlkeld, the first few weeks of Trump 2.0 illustrate that the volatility emanating from the U.S. “was arguably understated before Trump’s return” [see Fig. 3].

The potential irritants in the relationship that could flare up are well documented. Both sides have, at a minimum, made plans to work on these challenges. The biggest issue, in the Trumpian worldview, is the imbalanced trade relationship. On this count, the Feb. 13, 2025 joint leaders’ statement makes it clear that aim is to “more than double total bilateral trade to $500 billion by 2030” and that the two sides will “negotiate the first tranche of a mutually beneficial, multi-sector Bilateral Trade Agreement (BTA) by fall of 2025.”

India’s Commerce minister, Piyush Goyal, made a “sudden departure” for the U.S. this week “reportedly to hold urgent trade discussions, just weeks before President Donald Trump’s planned reciprocal tariffs are set to take effect.” Reports note that the minister “will seek clarity on US reciprocal tariffs to assess their impact on India” and “may also discuss potential Indian concessions and a trade deal to reduce tariffs and boost bilateral trade.” The Indian govt. already took some steps in the 2025 Budget, eliminating 7 high tariff rates and reviewing around 8,500 tariff lines pertaining to industrial goods (out of ~12,500 tariff lines).

In an interview with The Hindu, the Central Board of Indirect Taxes and Customs’ chairman said that in the 2025 Budget, the govt. did away with “peak rates of 150%, 125% and 100% which applied to just five items, but had created “bad optics” about India’s tariff structure.” He also pointed out that “while India’s peak custom duty rate is now 70%, the import duties on the top 30 items exported by the U.S. to India - led by crude petroleum, coking coal, aeroplanes, and liquiefied natural gas - are minimal, in the range of zero to 7.5%.”

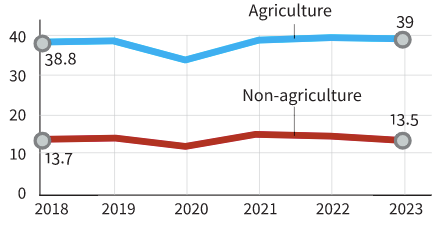

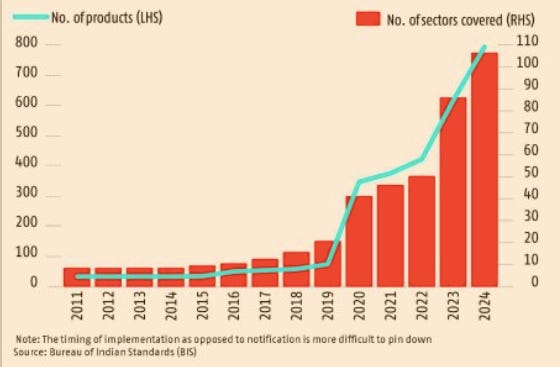

The degree to which these steps by the Indian govt. will mitigate any trade-related blowback from the U.S. administration remains to be seen. It is crucial to point out that India’s relatively high import tariffs are “mostly due to high tariffs on agricultural products to protect domestic producers” (see Fig. 4 & 5).

Many have pointed out that India and the U.S. have a “negotiating record” from Trump’s first administration, and this should aid in trade agreement talks. It is worth bearing in mind that last time, the two sides were engaged in trade discussions and were hoping to reach a limited trade agreement timed with Trump’s first visit to India (in February 2020). The 2020 joint statement noted that India and the U.S. hoped to conclude negotiations that would become “phase one of a comprehensive bilateral trade agreement.” Even then, a full trade agreement wasn’t in the offing. Robert Lighthizer (former US Trade Representative during Trump’s first term) in his book No Trade is Free, wrote the following about India-U.S. trade talks,

“After several sessions, it was obvious that these talks would not succeed. India was not in the habit of opening its market, and many of the concessions we needed were in the agriculture area, and at that time, India’s farmers were in a state of agitation for a variety of reasons… [Following a Modi-Trump meeting at the 2019 G7 summit in France] negotiations began in earnest… We raised out issues: tariffs, agriculture access, medical device impediments, barriers to e-commerce and insurance, discrimination in the electronic payment sector, fish subsidies, and the list goes on. We made headway but could never quite close a deal.”

On March 5, 2025, in his address to a joint session of the US Congress, President Trump cited high tariffs from countries including Brazil, India, and China and said that reciprocal tariffs would come into effect on April 2. The Indian govt. hasn’t officially responded to this, and Suhasini Haidar reported on this development writing,

“India’s inclusion in the list of countries that would still face reciprocal tariffs after April 2 is believed to be a disappointment for those in the government who believed that Mr. Modi’s visit, and the promise of “fair-trade terms” in the BTA, could have postponed Mr. Trump’s decision. However, officials say there is still time for negotiation with the Trump administration.”

A Hindustan Times report on this issue notes,

“According to people familiar with the ongoing talks, who spoke on condition of anonymity, the Indian side may escape the tariffs that Trump has threatened to impose from April 2 as both sides are actively engaged in constructive negotiations to address each other’s concerns, including tariff and non-tariff barriers.”

Another media report cited a senior government source saying, “it would be premature to panic on Trump’s reciprocal tariffs.” While govt. officials project a sense of confidence, experts point out that some of India’s “key export sectors may face some heat.” Clearly, a lot hinges on Minister Goyal’s meetings with his counterparts in DC.

There have been a number of interesting proposals that get to the heart of the trade issues and recommend ways to deal with these challenges. I want to highlight four pieces and the first is by Mark Linscott for the Hinrich Foundation. In his piece, Linscott notes that “six to nine months to conclude a first tranche trade deal is a very short period, even bordering on wildly unrealistic, depending on level of ambition.” He writes that it might be better for India to “lower its tariffs in key sectors as much as possible rather than leaving a good or sector out of the first tranche if the consequence is the United States raising its tariffs against India reciprocally.” Linscott also highlights India’s growing trend of using “quality control orders” [QCOs] that employ “India-unique industrial standards instead of international standards and require testing in Indian facilities, which can diverge from international best practices.” In a recent Business Standard article, a number of experts described QCOs are “a new instrument which combines the worst of policy’s protectionist, non-transparent, discretionary and micro-management instincts” and pushed for an immediate elimination of QCOs [see Fig. 6].

In Linscott’s view, tariff cuts might be the “most complicated challenge beyond a first tranche in a BTA” with questions around India’s ability to “make significant tariff and other concessions, even ones that are normally reserved for high-stakes FTA negotiations.” A potential silver lining in India-US talks on this subject is the fact that a ‘Bilateral Trade Agreement’ (BTA), as a term, is “somewhat unique” as it “is not a free trade agreement (FTA), and previous bilateral efforts to negotiate have never involved an FTA” providing some leeway for creativity as both sides engage in negotiations.

A second report on this issue is by Ajay Srivastava at the Global Trade Research Initiative (GTRI; I interviewed Mr. Srivastava for the first edition of the Policy Playbook - you can read the interview here). Srivastava presents five ways in which the Indian govt. could respond to US tariffs. Of the five options ((i) cut Most Favor Nation (MFN) tariffs, (ii) negotiate a deep FTA with the US, (iii) retaliate with higher tariffs, (iv) propose zero-for-zero tariffs, and (v) take no action), Srivastava argues that the best method to deal with this would be by,

“eliminating tariffs on most industrial products, provided the U.S. does the same. India should identify tariff lines where duty cuts won’t harm domestic industries, referencing its past FTA offers to Japan, Korea, and ASEAN. Agriculture may be excluded from the offer.”

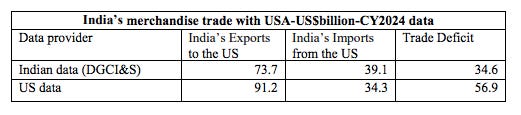

Srivastava also lays out a number of issues that India needs to explain to the US administration, including highlighting huge data discrepancies in the trade data as reported by official Indian and American sources [see Fig. 7].

A third report is by Akshay Sinha in The Indian Express (also cited above). Sinha recommends that India and the United States should pursue a ‘sectoral FTA’ as it presents a number of advantages, including

“It is more substantial than a basket of concessions and can be “big” enough to satisfy Trump. More importantly, it allows India to keep certain politically-sensitive industries — such as dairy and rice — off the table while offering access in other less sensitive areas.”

Crucially, Sinha writes, the Trump administration has shown a “willingness to negotiate secoral trade agreements,” having signed the US-Japan Trade Agreement (USJTA) in 2020. This recommendation echoes some of the suggestions laid out in a Foreign Policy piece by Mark Linscott and Kenneth Juster, where the two former US govt. officials see the USJTA as a reference for a potential US-India trade agreement. In his Indian Express piece, Sinha also recommends that the Indian govt. offer agricultural concessions to Trump. While this is an interesting proposition, I doubt it is politically feasible, especially when one keeps in mind that the US subsidizes its agricultural sector as well.

Finally, the fourth piece is an article by Prachi Mishra for Mint. Mishra argues that “the space vacated by countries directly targeted by US tariffs could be captured by Indian exports” and Indian firms now have a “chance to aggressively expand labour-intensive production, particularly in sectors like textiles.” Mishra presents a four-pronged strategy that could be deployed: “expedite free trade agreements, reform labour regulations, strengthen raw material ecosystems and create large special economic zones with comprehensive infrastructure.”

While the fourth piece by Mishra recommends policy reforms at a 30,000-foot view,1 the three other works cited above go into substantive details on how India and the US can productively engage on trade-related matters. All four pieces provide some insights into the India-US trade relationship.

Minister Goyal’s DC trip is scheduled to end this week (March 8, 2025), and we already have some indication of how the conversation went.2 On March 7, 2025, President Trump said,

“India charges us massive tariffs. Massive. You can't even sell anything into India. It is almost restrictive. It is restrictive. We do very little business inside. They have agreed, by the way, they want to cut their tariffs way down now.”

He also (rather crudely) stated that India had agreed to cut down tariffs because "somebody is finally exposing them for what they have done.” In addition to this, US Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick, in remarks to a media organization on March 7, 2025, said,

“The United States is interested in doing a macro, large scale, broad-based trade agreement with India that takes everything into account, and that I think can be done… Let’s bring India’s tariff policy towards America down, and America will invite India in to have really an extraordinary opportunity and relationship with us.”

Per this Bloomberg report,

“Lutnick on Friday also called for India to open up its agriculture sector, a deeply politically sensitive sector in India, saying that quotas or limits might be possible to allow US imports.”

The actual statement made by the US secretary contains pretty strong language,

“India’s agri market has to open up… Now how you do that, the scale in which you do that (has to be seen). Maybe we should have quotas, limits. Be smarter when you have your most important trading partner on the other side of the table. You can’t say it is off the table.”

There are significant expectations from the U.S. side on the nature of the bilateral trade agreement they expect to sign with India. That the Commerce Secretary has publicly called for India to open up the agri sector is noteworthy. There is less than a month till tariffs aimed at India kick in, and the timeline for figuring out the BTA is pretty short (by fall this year). Given these challenges, one would be hard-pressed to predict a positive outcome on the tariffs and trade front short of some significant concessions from the Indian government.3

Given these challenges, the Indian govt. could potentially deal with the US administration by,

Pointing out some of the concessions the Indian govt. has already made by reducing tariffs on several fronts, which is demonstrative of a genuine willingness to engage with US concerns

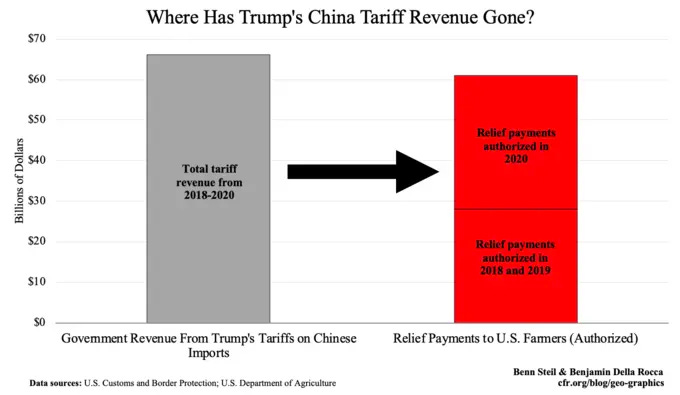

Highlighting that the US agricultural sector is subsidized as well and that engaging in escalatory tariffs wars is detrimental for all parties involved, including, especially for US farmers (a 2020 Council on Foreign Relations study found that a large chunk of the US government revenue from tariffs on Chinese imports went to US farmers to “offset their losses from Chinese trade retaliation”; see Fig. 8)

Figure 8. A huge portion of govt. revenue from tariffs on Chinese imports went to US farmers during Trump 1.0 (source: CFR)

Demonstrating strength and publicly responding to President Trump’s rhetoric on tariffs. Thus far, there have been no public statements from the Indian govt. on US statements. It is well documented that President Trump has an affinity for ‘strong’ leaders, and US-Mexico negotiations on tariffs are illustrative of how savvy leadership, as demonstrated by Mexico’s President Claudia Sheinbaum, can help de-escalate tariff wars

Making plans to implement tariffs that would strategically impact key US exports. This was a step taken by several states during Trump 1.0 (see this article on how the EU and other major US trading partners implemented retaliatory action that affected “$27 billion of US agricultural sales to the world” or this report on Chinese retaliation). This measure could be deployed in the scenario where talks on tariffs fail and the Trump administration institutes tariffs on India

For a more detailed paper on the reforms that India needs, see this recently released World Bank report, ‘India: Becoming a High-Income Economy in a Generation.’

It is important to point out that all the on-the-record info in the public domain has come from the American side.