India in 'World Energy Outlook 2024' & notes on energy-related challenges

Key energy trends and data points on India + some notes on energy-related challenges (EnergyNotes #1)

International Energy Agency (IEA) released the ‘World Energy Outlook 2024’ this week. Some key quotes & data points from the report on India1 -

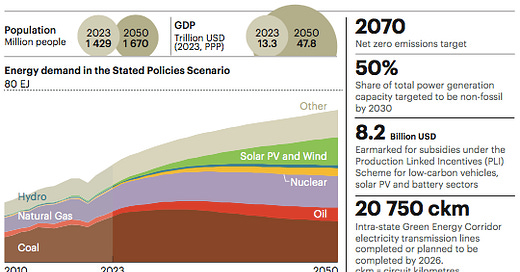

Energy demands: “The population size and the scale of rising demand from all sectors mean that India is poised to experience more energy demand growth than any other country over the next decade.” [277]

Key trends: In the STEPS [Stated Policies Scenarios]2, “the largest sources of rising demand for energy are, in descending order, India, Southeast Asia, the Middle East and Africa.” [17]. “By 2035, iron and steel production are on track to grow by 70%; cement output is set to rise by nearly 55%; and the stock of air conditioners is projected to grow by over 4.5-times, resulting in electricity demand from air conditioners in 2035 that is more than Mexico’s total expected electricity consumption that year.” [277] India sees the largest “impact from poor air conditioner efficiency at about 30% of the total increase in electricity demand.” [191] Due to the extended heat waves over much of India during May-June 2024, there was a “doubling of air conditioner sales” in 2024. [189]

Coal: India is the “second-largest coal consumer and is the main driver of future demand growth: its coal use increases in power to 2030 and in industry to 2040 in the STEPS, and its energy-related CO2 emissions continue to rise before peaking around 2035.” [150] India, along with Japan and Korea, accounts for an estimated “35% of global imports” of coal. [151] “Coal prices surged amid supply shortages in 2021 and were followed by even higher prices in 2022, leading major coal consumers like China and India to scale up investment in domestic production.” [152] India almost overtook Indonesia “as the second-largest coal producer following two years of record increase in production, and it plans to double coal output by 2030.” [150]

Coal v RE: “By 2035, the consumption of coal in industry would have grown by 50%, with its share in total industry demand remaining at similar levels as today.” [277]

Road transport & e-vehicles: “While an increasing share of vehicle sales are electric, the simultaneous growth of internal combustion engine vehicles results in oil demand from road transport rising 40% by 2035 in the STEPS, contributing to an increased dependence on oil imports.” [277-78] In part due to “available incentives, 5% of two-wheelers, 50% of three-wheelers and 7% of buses sold in India today are electric. Over the next decade, two/three-wheelers and buses see faster rates of electrification in the STEPS than passenger cards because of existing government support, consumer preferences, and the state of market development.” [278]

Geopolitics & energy: “Imports of Russian oil to India increased from 2% of total oil imports in 2021 to 25% in 2023.” [76] With India poised to become “the main source of oil demand growth, adding almost 2 million barrels per day (mb/d) to 2035” [18], energy security and national security get further enmeshed.

Funding the green transition: “[U]tility-scale solar PV and wind projects in Brazil or in India have built up a successful track record of mobilizing private capital for several years, and only limited interventions are required on the financing side from the public sector.” [65]

As the report makes clear, India’s size and growing economy ensure that it will see some of the highest energy demand growth in the coming decades. India’s energy use has doubled since 2000, “with 80% of demand being met by coal, oil, and solid biomass.”

The government has set ambitious targets to facilitate economic growth, achieve energy security, and tackle climate change-related challenges. At the 2021 COP26 Summit in Glasgow, Prime Minister Modi outlined 5 targets the government set to tackle climate change and achieve its energy transition goals [see Fig. 3].

A key challenge for India is to decouple economic growth from CO2 emissions. Recent studies show that certain countries have “managed to achieve economic growth while reducing emissions” [see Fig. 4].

Decoupling the two - growth and emissions - remains a thorny problem as India is still a nation with low per-capita energy consumption relative to other economies. Adam Tooze mapped out how (extremely unequal) energy transitions will play out on the basis of per-capita energy consumption and growth rates [see Fig. 5].

Furthermore, as Johannes Urpelainen notes in Energy and Environment in India,

“For India, economic development and poverty alleviation are nonnegotiable priorities. As long as hundreds of millions continue to live in poverty,3 any approach that compromises India’s economic development or constrains its carbon space is off the table. This logic is readily seen in the 2070 net zero commitment, which strikes a delicate balance between meeting global expectations while avoiding a premature shrinking of India’s carbon space.” [p. 170]

India’s G20 sherpa, Amitabh Kant, highlighted the scale of the challenge at a recent business summit: “India must be the first country in the world to industrialize through a process of decarbonization.” A bright spot in India’s energy transition story has been the growth in renewable energy installations. Urpelainen, in Energy and Environment in India, outlines the impressive strides India has made,

“According to the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE), India has installed 46 gigawatts of solar power and 40 gigawatts of wind power by September 2021. This is a massive increase from December 2014, when MNRE estimated that wind power stood at 22 gigawats and solar at only 3 gigawatts. Although COVID-19 slowed down India’s progress temporarily, renewables have made impressive progress, and their long-term trajectory is promising thanks to low generation costs, improvements in battery storage, and policies at the national and state levels.” [p. 11]

A notification from MNRE on Oct. 14 further underscores these achievements - as of Oct. 10, 2024, India’s total renewable energy capacity crossed the 200 GW mark with total renewable energy-based electricity generation capacity at 201.45 GW, accounting for 46.3% of India’s total installed capacity [see Fig. 6].

These trends are remarkable given the state of RE capacity even a decade ago. While these achievements ought to be lauded (as they are), there remain structural issues.

In a speech on Oct. 14, 2024, the Union Minister for Power (and Housing & Urban Affairs), noted that by 2047, India’s anticipated power demand will reach 708 GW and stated that “this is not just about increasing capacity; it’s about reimagining our entire energy landscape.” In reference to the delta between capacity and demand, the Minister said,

“Till now the ratio was that capacity was double of the power demand. But as we install more RE, this ratio will change because RE sources do not have continuity (variability) particularly for solar. So, we will have to have more RE capacity. By 2047, our demand will be around 708 GW, but our capacity will have to be increased four times. So now capacity is double, but it has to be tripled. This is the challenge.”

This 30,000-foot view (coupled with key data points from the 2024 IEA report presented above) makes clear the severe challenges ahead if one is to - as the Union Power Minister stated - reimagine India’s energy landscape.

Going a level deeper, the myriad challenges that afflict India’s energy landscape become stark. I will cite two examples below that provide a more nuanced picture of the issues at hand.

The first is to do with India’s solar sector. Writing on how intermittency has been “the bugbear of the renewable sector,” M. Rajshekhar (author of the excellent Despite the State) has written an incisive three-part series on the state of India’s solar sector. [Part 1, 2, and 3]

Rajshekar documents the transformation in the solar sector,

“Three years ago, it was in trouble. Between weak market design and muddle policy variably pushing indigenisation and faster solar deployment, solar capacity addition was slowing. Much has changed since. Prices of solar modules have kept falling, now reaching previously unimaginable levels… In response, though, India has erected trade barriers, replacing erstwhile import duties with more stringent policies - like the Approved List of Module Makers (ALMM) revived this April, and Domestic Content Requirements — to ensure local procurement. A PLI [Production Linked Incentives] scheme has been rolled out as well — to manufacture not only modules, but also cells, ingots, wafers and polysilicon locally — in the hope of decoupling India’s solar sector from that of China. With that, the country’s module manufacturing sector is seeing a boom.”

So far so good. This boom in the manufacturing sector translates to greater installed solar generation capacity. Where is the issue? Rajshekar goes a step further and [in part 1 of the 3-part series] illustrates how “domestic demand continues to stay low,” “domestic prices of locally-manufactured modules have spiked over the past two years,” and manufacturers and developers push part of their costs onto DISCOMs [distribution companies] and customers.

In part 2, Rajshekhar uncovers how entities one wouldn’t expect are part of India’s solar panel manufacturers within the government’s ALMM [Approved List of Models and Manufacturers], including Sri Sri Ravi Shankar’s Art of Living Foundation, ceramic tile-makers from Morbi, and bidi manufacturers from Raipur.

Firms that are part of the PLI scheme and the “only vertically integrated players in town” haven’t started production yet with industry insiders expecting that some of these manufacturers would use their products to “initially decarbonize their own operations,” or are “exporting modules - mostly to the US.”

Why are certain firms [that one wouldn’t expect to be in the business of manufacturing solar modules] entering this space? Rajshekar writes,

“[F]irms which entered seeing others make a killing, is competing on price, often at the cost of quality. “When we check the samples, a 550 Wp solar module is giving the rated wattage,” a developer told MercomIndia. “But when we use them in the project, they give less wattage.” ALMM, said the Chennai-based sales manager, should review installed panels’ performance every two or so years.”

Where do these quality issues leave us? According to the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) and JMK Research & Analytics (from May 2024),

“The current module nameplate capacity of 68 gigawatts (GW) is insufficient. After accounting for operational efficiency, exports and low-quality modules, the supply of high-efficiency domestic modules to the Indian market will only be around 20-22 GW, much less than the annual solar installation target of 30-35 GW, apart from another 5 GW target for rooftop solar.”

A second example pertains to energy storage. As per a 2022 report from NITI Aayog and Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI) India, India is at a “nascent stage of creating a domestic cell manufacturing ecosystem” as it has a “negligible presence in the global supply chain for manufacturing of advanced cell technologies.”

Akin to the PLI scheme for high-efficiency solar PV modules, the government has a PLI scheme for Advanced Chemistry Cell (ACC) battery storage. The Union Cabinet approved the scheme for battery storage in May 2021, with three bidders selected (of a total of 10 bids; major multinational firms didn’t participate in the process as this 2023 International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) and Invest India report highlights) in July 2022. The IEA, in the 2023 Global EV Outlook report, has dubbed the scheme and its targets (establishing 50 GWh in domestic manufacturing capacity with an initial domestic value-add of 25% that ramps up to 60% within 5 years) as “particularly ambitious” since “there is currently no significant domestic battery cell manufacturing in India.”

A 2023 report by the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW) notes,

“As per the ACC PLI scheme, we can expect 60 per cent domestic value addition by around 2027 ot 2028. Even before this, the mother units will be required to provide 25 per cent domestic value addition by 2024. Attaining the initial 25 per cent value addition by solely setting up cell manufacturing might be difficult if commodity prices stay inflated, and manufacturers might need to add some quantity of component manufacturing as part of their mother units. They may also keep the sales prices of the manufactured cells high, with these prices being offset by the subsidies disbursed.”

When it comes to energy storage - which will alleviate the many pressures on India’s power sector with a greater uptake of REs4 - the Indian manufacturing ecosystem is in the early stages of what appears to be a years-long drive towards indigenization.5 The laudatory way in which the government presents the PLI scheme for batteries belies extant challenges.

This quote by an industry executive whose company has won government tenders to set up battery energy storage systems (BESS) is telling -

“[N]o single agency in India can certify battery energy storage systems, which means we need to send the entire package outside India for certification. India currently lacks cell manufacturing capacity, making it crucial for us to have a comprehensive understanding of cell chemistry and technology to ensure that imported cells meed project requirements.”

The two examples cited above make clear the many challenges that afflict India’s energy landscape. This is without even getting into the financial condition of India’s DISCOMs [per a 2024 NIPFP report, by 2022-23, state-owned DISCOMs had “collectively accumulated losses of around Rs. 6.77 lakh crores”], reliance on China [for instance, India imports ~60-65% of the “total component requirements for battery packs from China”], dependency on imported raw materials, negligible to limited R&D capabilities, and shortage of skilled talent [this McKinsey report on chemical manufacturing in India underlines this issue noting that “about 1,400 chemical engineers graduate from India’s top 25-30 universities every year” with a majority leaving for higher studies or switching streams].

Unless stated otherwise, all quotes are from the IEA report with the corresponding page number in brackets.

STEPS “provides a sense of the energy sector’s direction of travel today, based on the latest market data, technology costs and in-depth analysis of the prevailing policy settings in countries around the world. The STEPS also provides the backdrop for the upside and downside sensitivity cases.'“ [15-6]

According to the latest ‘Global Multidimensional Poverty Index 2024,’ released by the UNDP on October 17, 2024, India has the highest number of people living in poverty (234 million). More than 40% of the people who are poor are children aged 0-17.

Alex Rutter, who consistently writes really informative pieces on India’s energy landscape at ‘energywithalex,’ notes that “RE deployment in India has typically been viewed through a climate lens rather than a development lens,” and that “by continuing to miss RE installation targets and prioritize fossil fuel imports, India is severely compromising its development.”

Samrath Kochar, founder of Trontek, has authored an article highlighting 6 challenges to battery cell manufacturing in India - i) supply chain bottlenecks, ii) technological gaps, iii) infrastructure deficiencies, iv) regulatory/policy hurdles, v) environmental concerns, and vi) financial constraints.