On July 5, 2024, national elections in the United Kingdom saw the Labour Party sweep to power in a landslide, winning 412 out of 650 seats. The incumbent Conservative Party, with a tally of 121 seats, was routed. This was the Conservative Party’s worst performance in its history. The 2024 election result represented a turnaround for the Labour Party, which back in 2019 had suffered its “worst electoral defeat in almost a century."

Given my limited knowledge of UK politics, I have deferred to analyses by experts, and compiled pieces I found to be informative on i) what the results say about UK’s politics, ii) the state of play for India-UK ties, and iii) notes on the new UK Prime Minister (PM) Keir Starmer and the (stunningly) brief transition period between an outgoing and incoming PM.

I. 2024 UK Election Results -

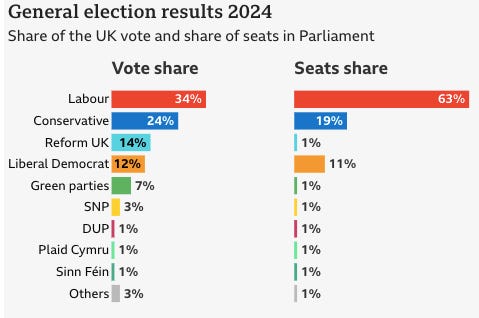

The Labour Party won 412 seats, the Conservative Party 121 seats, the centrist Liberal Democrats 71 seats, Reform UK (a relaunch of the Brexit Party), and the left-wing Green Party 4 seats each. In addition to the Conservatives’ dismal performance, the Scottish National Party (SNP) also underperformed. The SNP was “hit by a succession of controversies around its finances and fell to just nine seats overnight.”

The BBC reported that there were a “number of notable defeats for Labour to independent candidates campaigning on pro-Gaza tickets - especially in areas with large Muslim populations” and that the Labour Party has “faced growing pressure over its stance to the conflict.”

What explains the Conservative Party’s poor performance? In addition to anti-incumbency [the party had been in power for 14 years], the Economist offers this explanation -

“The Conservatives won around 24%, its lowest vote share in modern history. The reason? Nigel Farage’s populist Reform UK party, which won an estimated 14% of all votes cast.”

Where there would be a split among progressive voters earlier, now there is a reported split among conservative voters. The Economist further notes, the Conversative Party must -

“decide what to do about Mr Farage and his insurgent party. Put simply, he must be buried or bedded. The Conservatives could go on the attack. They could charge Reform uk with being a tinpot operation whose candidates include cranks and racists. They could say that Mr Farage has dodgy views on everything from Russia to Donald Trump. Mr Farage insists he wants to destroy the Conservative Party. Why shouldn’t the Conservative Party fight back? The alternative is to woo him. It would be a political marriage of convenience. Mr Farage brings a unique charisma that was enough to persuade millions of British voters to support a party that barely exists beyond a skeleton staff… What the Conservatives cannot do is continue with its current policy of aping Reform-style policies while insisting the party itself is beyond the pale. The Conservatives must pick either political murder or merger.” [emphasis added]

Voters’ shift from the Conservative Party to Reform UK was picked up by Richard Seymour in this New Left Review piece where he noted that “the Conservatives plunged from 44% to 24%, feeding into a surge for the far-right Reform UK which, with 14% of the vote, took four seats.” Seymour, however, makes the case that the Labour Party’s landslide victory isn’t all that is being made out. He argues:

“A majority without a mandate, and a landslide that isn’t a landslide. Labour won 64% of the seats with 34% of the vote, the smallest ever vote share for a party taking office… Never has there been such a yawning gap between the fractal pluripotencies of the age and the suffocating politics at the top. Few governments have been this fragile coming into office. There will be no honeymoon. Labour and its leader are deeply unpopular; just less so than the Conservatives for now.” [emphasis added]

Not everyone shares Seymour’s assessment on the vote share to seat share conversion [see Fig. 1] in UK’s first past the post system and what it implies for the Labour party. For instance, Sam Freedman posted the following on X/Twitter:

“Have to say when Cameron became PM of a majority govt in 2015 on 36.9% of the vote I don’t remember quite so much concern about vote shares. The two Brexit elections were anomolise due to a single point of polarisation. Other than them no party has hit 40% [vote share] in an election since 2001.” [emphasis added]

Crucially, James Butler sets the 2024 result in a historical context in this London Review of Books article:

“Labour’s victory has appeared inevitable for so long that it’s easy to understate how rapid and total the change has been, and how emboldened the party ought to be. Boris Johnson won the 2019 election with a majority of 80 and 44 per cent of the popular vote. Just five years later, with one constituency in the Highlands still to declare, Starmer’s Labour has won 412 seats – a majority of 175 – while the Tories clung on to just 121… Victory arrives as a shock because Labour is habituated to losing. It has spent two-thirds of the past century out of office and many of its incoming MPs lack parliamentary experience, let alone experience of government.”

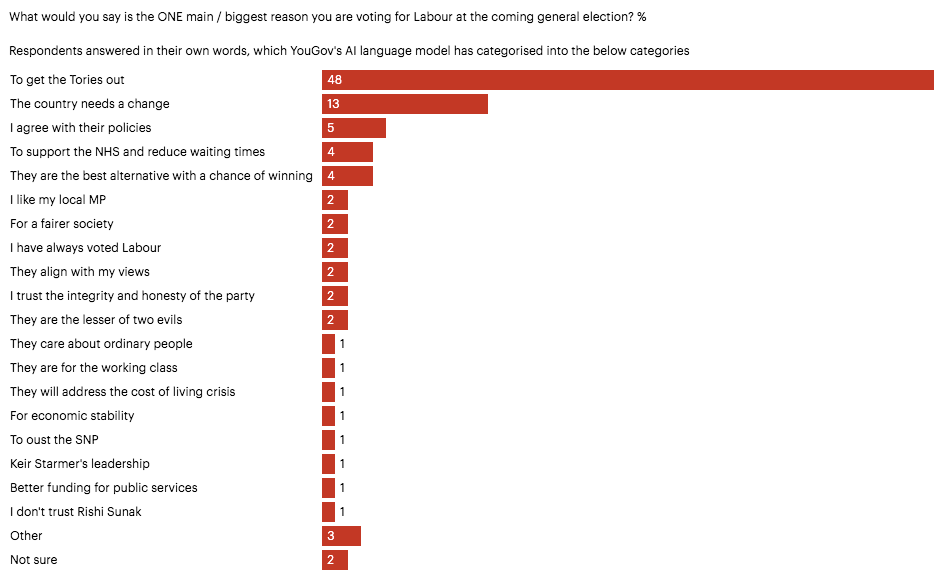

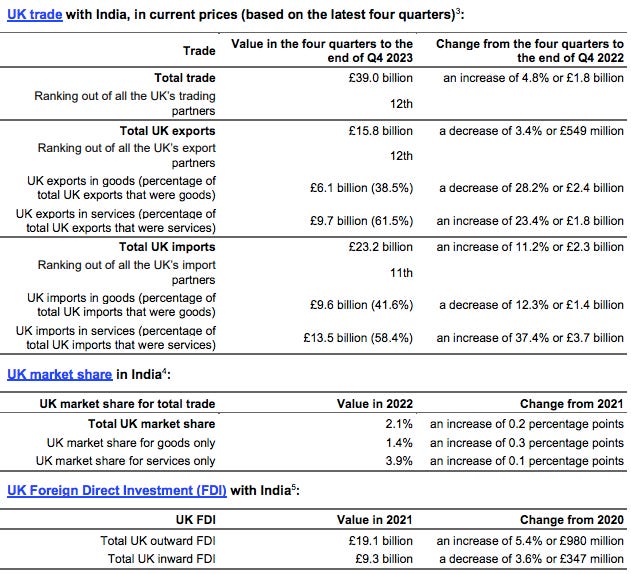

Many commentators have noted that in 2024, votes were anti-Conservative party, and not necessarily pro-Labour Party. A YouGov poll conducted between June 21 and July 1, 2024 best demonstrates this [see Fig. 2].

One of the key tasks awaiting the new government? The Financial Times notes that the Starmer government is expected to:

“set out an extensive package of pro-development planning reforms within days, as part of plans to “get Britain building again” and address the country’s acute housing shortage… Starmer, who swept to power in a landslide election win, wants to reimpose previous house building targets on local councils that were watered down by the previous Conservative government… A senior Whitehall official said Labour was expected to try and unleash investment in house building through greenbelt reforms that would release “grey belt” areas of ugly yet protected land for development.”

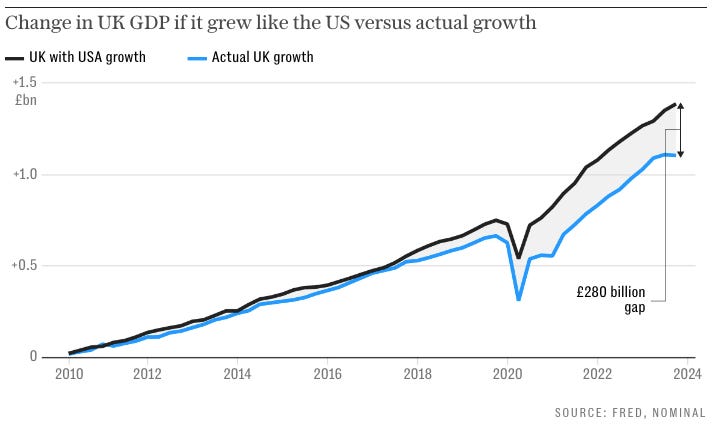

These reform measures are part of the Labour Party’s plan to “pull the UK out of a decade of low growth and productivity.” How bad is the economic condition? A Telegraph piece (from March 2024) noted that the Conservative Party’s track record on economic growth over the past decade has been “anemic at best” [see Fig. 3].

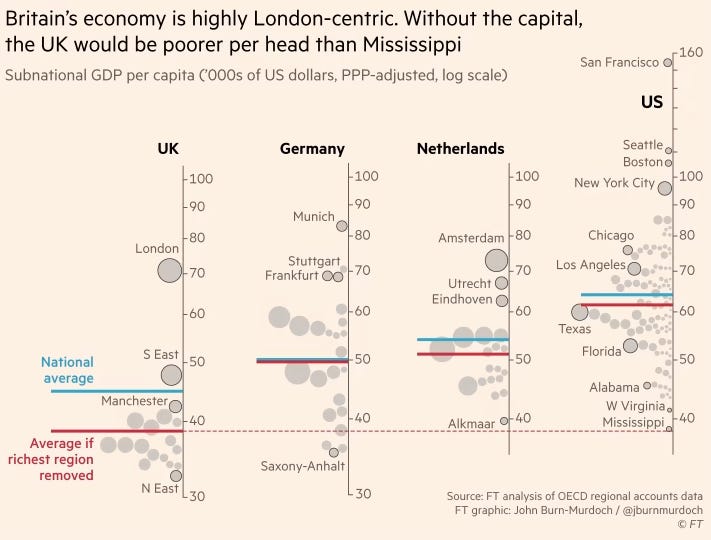

While looking up UK’s economic story, I came across this (mind-boggling) chart that shows that without London (the richest region in the UK), the average living standard in the UK would be lower than every state in the United States (see, Fig. 4; h/t: this thread by Keith Woods).1

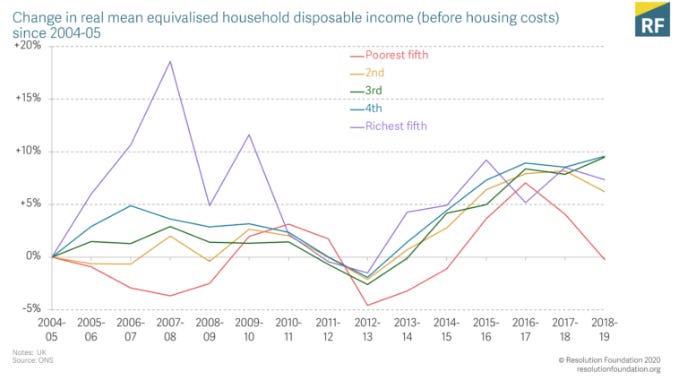

This economic downtrend is not just a story about the impact (and arguably, mishandling) of the COVID-19 pandemic. This Resolution Foundation note (from March 2020) by Adam Corlett found that “real mean disposable income [in the UK].. was no higher in 2018-19 than in 2007-08.” Notably, one of the worst-hit groups of the UK’s economic performance has been the poorest fifth of the population [see Fig. 5]. Corlett notes:

“Today’s data shows that the income of the poorest fifth of the population was no higher in 2018-19 than in 2004-05 – and that’s despite not seeing the kind of massive income fall that the richest saw following the financial crisis.”

James Butler laid out the challenges the newly-formed government faces:

“Britain is stuck in a doom loop. The economy isn’t growing, so the country is starved of the cash it needs to rebuild. Its institutions degrade. Money earmarked for investment gets swiped for day-to-day costs (schools and hospitals both have repair backlogs amounting to £12 billion). Failure to invest means failure to grow, again, and the cycle worsens and repeats. External shocks expose our weakness: Britain’s recovery from the financial crisis, the pandemic and the energy spike has been more protracted and less complete than in other advanced economies.” [emphasis added]

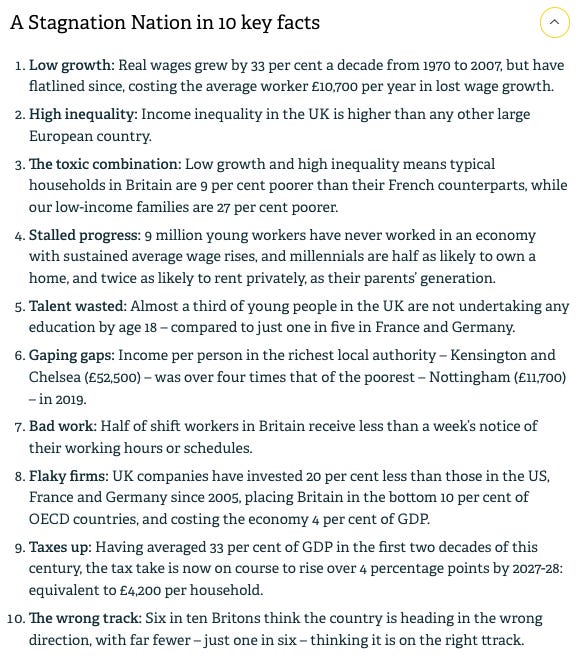

A Resolution Foundation report that recommends a “new economic strategy for Britain” has a helpful guide outlining why the authors believe the UK is ‘a stagnation nation’ [see Fig. 6].

Needless to say, the Starmer government has challenges aplenty. Some have (correctly) pointed out that the Labour’s party’s priority - “to solve the problem of Britain’s stagnant productivity” - is the right one.

II. India-UK ties:

The Labour Party’s return to power has prompted some worries about how the India-UK bilateral relationship might pan out. There is a historical basis for this concern. In an Indian Express article (from July 3, 2024), C. Raja Mohan reminded readers of what happened the last time the Labour Party was in power:

“Labour’s return to power might reignite some of India’s anxieties about bilateral ties due to the disastrous turn in India-UK relations in the late 1990s when Labour presided over a visit by Queen Elizabeth II to India in 1997. Meant to signal post-colonial reconciliation on the 50th anniversary of India’s Independence, the visit became a lesson in how not to organise major diplomatic events. In a stopover in Pakistan during the mission’s visit to India, the newly-minted British Foreign Secretary, Robin Cook, talked about helping mediate on the Kashmir question. Inder Kumar Gujral, the Indian Prime Minister travelling in Egypt at that time, dismissed the offer and called Britain a “third-rate power” wallowing in delusions about its post-imperial weight in the world. The Queen’s visit to Jallianwala Bagh to express regret at the 1919 massacre was to be the sombre centrepiece of the visit. But Prince Philip, the Queen’s Royal Consort, remarked that the Jallianwala Bagh death count may be exaggerated and triggered a massive uproar in India. Although British PM Tony Blair sought to limit the damage, the squabbling over Pakistan and Kashmir continued to cast a shadow over bilateral relations under Labour’s tenure. Cook’s articulation of an “ethical foreign policy” that had support in the Labour Party, coupled with the promotion of identity politics and pandering to anti-India groups, put the ties between Delhi and London on shaky ground.” [emphasis added]

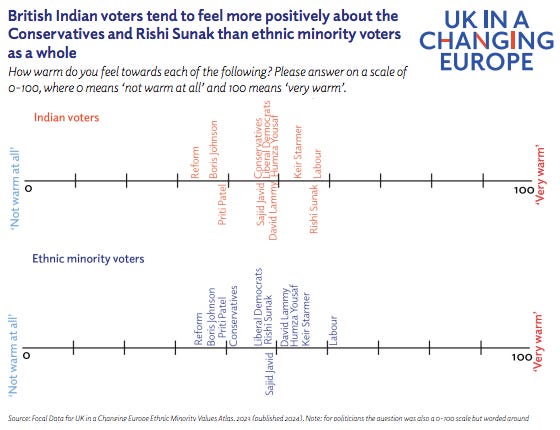

It is pertinent to note here that while the Indian govt. may have a certain view of the Conservative Party and the Labour Party, British Indian voters have much warmer feelings for the Labour Party (than they do for the Conservative Party, and on average, British voters feel more positively about the Conservative Party (And Rishi Sunak) than ethnic minority voters in the UK as a whole; see Fig. 7).

Notwithstanding the troubled relationship between India and the UK (as Dr. Mohan outlined above), he is much more optimistic about the relationship’s future. A key reason? David Cameron, leading the Conservative Party to victory in 2010, “made an early visit to India and signaled the desire to put the past behind.” There was movement from the Indian side as well, as a UK-India strategic partnership that was signed in 2004 was upgraded to an ‘Enhanced Partnership for the Future’ in 2010.

The relationship still took a decade to strengthen, but the Conservative Party’s initial steps in the early aughts helped. The 2020 India-China clash was a significant turning point as it led to a stronger west-ward turn on part of India coupled with a shift (that was occurring parallely) in UK-China ties from 2019-2020 onwards. As Gulshan Sachdeva argues, “geopolitical shifts, including the rise of China and closer India-US and India-EU ties, have played an important role in bringing India and the UK together.”

Writing in the Hindustan Times, Walter Ladwig and Anit Mukherjee note:

“Only in the aftermath of the 2020 border clashes with China did India see the UK and other European countries as potential partners. Significant credit must go to British Prime Minister Boris Johnson and his successors who sought to change India’s perception of Britain: Working to reduce economic exposure to China, naming and shaming Pakistan for financing of terrorism, announcing a significant “tilt” towards the Indo-Pacific, and relaxing visa restrictions on Indian students and workers. Such initiatives were welcomed by New Delhi, generating a once-in-a-generation buzz about the future of the bilateral partnership.” [emphasis added]

In the last four years, engagement between India and the UK includes -

May 2021: Launch of the ‘2030 roadmap for India-UK future relations’; the document states that through the roadmap, the India-UK relatio’ship will be elevated to a ‘Comprehensive Strategic Partnership’

January 2022: India and the UK began negotiations for a trade agreement (an initial deadline of October 2022 was set by both sides that was not met; negotiations continue with the former International Trade Secretary Badenoch quoting former PM Rishi Sunak as saying that it is the “quality, not the speed, of the deal” that matters)

April 2022: India’s PM Narendra Modi met with then PM Boris Johnson for ‘talks on defense, diplomacy, and trade’

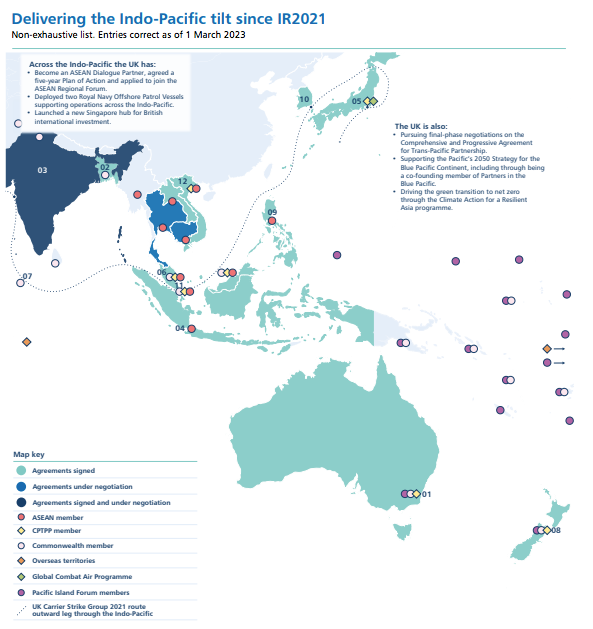

March 2023: The UK government published a ‘refresh’ of a 2021 integrated review of security, defense, development and foreign policy resulting in the ‘Integrated review refresh 2023: Responding to a more contested and volatile world’ policy paper; India found a rather prominent place [see Fig. 8] in the policy document and the UK government stated that it would “closely align our efforts with partners pursuing Indo-Pacific strategies” including India

September 2023: UK PM Rishi Sunak visited India (to attend the G20 summit); a press release after the meeting noted that the two sides “agreed it was important to build on the past and focus on the future, cementing a modern partnership in cutting-edge defence technology, trade and innovation.”

January 2024: India’s Defense Minister Rajanath Singh visited the UK (the first defense ministerial visit in 22 years)

Given all this activity, in a rather short period of time, there is some momentum in the bilateral relationship for the new UK government to build on. The Labour Party has indicated that it seeks to build on the work done by the Conservative Party in advancing the bilateral relationship. The Labour Party manifesto states:

“Labour will build and strengthen modern partnerships with allies and regional powers. We will seek a new strategic partnership with India, including a free trade agreement, as well as deepening co-operation in areas like security, education, technology and climate change.” [emphasis added]

In a recently concluded event on India (organized in late June), then UK Shadow Secretary of State for Foreign, Commonwealth and Development, David Lammy (who is now the Foreign Secretary in the Starmer government), stated that the Labour Party was looking forward to getting the “free trade deal done” and attacking the Conservative Party, noted that:

“We [the UK and India] need a reset and a relaunch in our relationship. Because the Conservatives have time and time again over promised and under delivered when it comes to India. And that leaves me frustrated - frustrated at the missed opportunities, frustrated at the shared prosperity that is passing us both by which is our ambition to unlock… Britain will remain and seek to ramp up its security partnership with India from military to maritime security, from cyber to critical and emerging technologies, from defence industrial cooperation to supply chain security. We are India’s friends and we are right behind her. This is our message which the UK Carrier Strike Group will carry to the Indian Ocean in 2025 to train and operate with Indian forces. In a world that is more and more contested, this is a friendship not only made of speeches but real actions in the real world [emphasis added]

Clearly, the Labour Party is making all the right noises when it comes to the India-UK relationship. Keen observers of the bilateral relationship and Indian foreign policy have recommended ways for the two countries to strengthen the partnership.

C. Raja Mohan argued that one of the two crucial tasks for India is to:

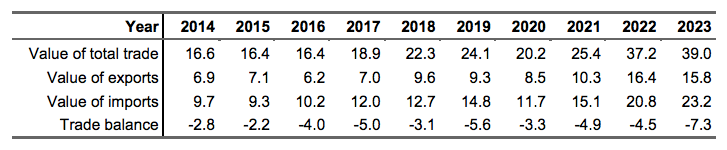

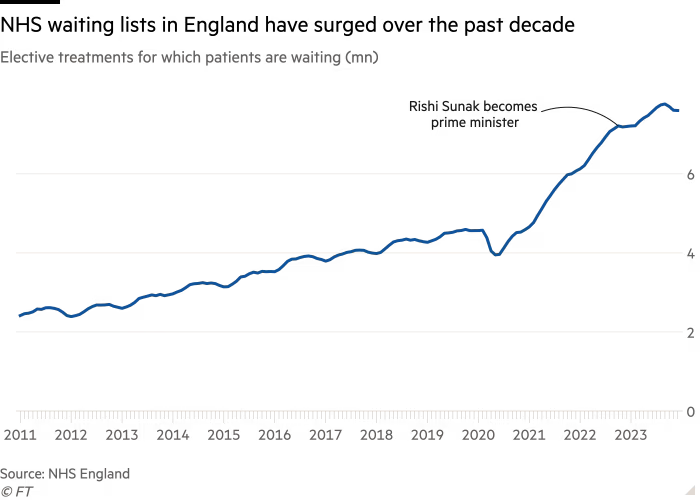

“build on the positive potential that limits the salience of the negative factors. Shedding misperceptions about Britain is equally important. Gujral was wrong when he called Britain a “third-rate power” [see quote above]. In the mid-1990s, Britain’s GDP was higher than China and India put together. Today, India certainly has a slightly bigger economy than Britain (nearly $4 trillion to $3.5 trillion). But India, with a per capita income of less than $3,000 (Britain is at $50,000), has much to gain from a deeper partnership with London. Delhi should stop underestimating the relative importance of Britain for India. India’s exports to Britain today, at nearly $30 billion, are nearly six times the exports to Russia [see Fig. 9 & 10]. Although far behind the US and China, Britain is among the front-ranking middle powers. Its financial clout, technological depth, and global reach make Britain a force multiplier for a rising India.”

Ladwig and Mukherjee list four steps the two countries can take to build on bilateral ties:

“First, bolstering Britain’s presence across the Indo-Pacific is a step in the right direction. Since the much-heralded Integrated Review in 2021, Britain has intensified its engagements across the region — ramping up its diplomatic and military cooperation… The challenge lies in maintaining this level of focused attention. Second, defence engagement has been one of the strongest pillars of India’s interactions with its closest partners — from Russia and Israel to France and the United States (US). Britain should learn from and emulate the US experience… Third, the UK may not enjoy the luxury of walking away from Pakistan. Nevertheless, if British officials truly believe their relationship with Islamabad is not comparable with the partnership with Delhi, that must be continually demonstrated via action, not just words. Ultimately, India will judge Britain on its behaviour in the next India-Pakistan crisis. Finally, New Delhi must value the potential for cooperation between the two countries. Gloomy assessments about Britain’s defence posture have led India to significantly reduce its defence attaché posts in London… Such an assessment ignores Britain’s capabilities in jet engines, undersea systems and emerging technologies like quantum computing and cyber which are highly valued by the Indian military.” [emphasis added]

There is no dearth of ideas on how the two countries can build on their relationship. One of the most fascinating ones, that would be welcomed by governments in London and New Delhi, revolves around exploring deeper defense ties. As India continues to diversify its arms imports and ramp up its domestic defense manufacturing capabilities, there is great scope for the two countries to collaborate (as Ladwig and Mukherjee propose).

The two governments clearly recognize this. During the April 2022 meeting between PM Modi and then PM Johnson, the latter stated that the UK is “creating an India-specific Open General Export License, reducing bureaucracy and slashing delivering times for defense procurement.” The Open General Export License was published in June 2022, and the document lists the licensing grants and exclusions.2 The Indian Defense Minister’s visit in January 2024 included:

“The signing of a Letter of Arrangement between India’s Defence Research and Development Organisation and the UK’s Defence Science and Technology Laboratory focused on next-generation capabilities. Several new joint initiatives were agreed, for instance on logistics exchange between the UK and the Indian Armed Forces, and the UK also announced its plans to send the Littoral Response Group to the Indian Ocean and the Carrier Strike Group to operate and train with Indian forces in 2024 and 2025, respectively.”

One of the more is-this-really-possible ideas that I came across was a proposal by the UK Foreign Affairs Committee that noted -

"We see advantage in working with the Quad to develop a coordinated strategy covering the whole Indo-Pacific maritime area, and applying to join the Quad at such time as the existing members feels is appropriate. Given the strength of our bilateral defese relationships with Quad members and the correlation between the UK’s and Quad’s objectives, the UK should seek to join the Quad.”

The UK Foreign Affairs Committee also recommends “the creation of a trilateral maritime freedom of movement cooperation agreement, made up of Japan, India and the UK, focused on joint exercises in the region.” An interesting suggestion (one that would potentially be welcomed by Indian counterparts) is the UK Foreign Affairs Committee’s prescription that:

“Unless already included in the FTA, the [UK] Government should also consider negotiating agreements with India similar to the UK-Australia supply chain and critical minerals agreements to establish shared principles of supply chain risk identification and mitigation. The UK should seek to increase its reliance on India for manufacturing and pursue enhanced maritime security cooperation.” [emphasis added]

There will be irritants in the bilateral relationship, including the UK’s ties with Pakistan, and fallout from diasporic politics. Civil unrest in Leicester3 in 2022 (involving British Hindus and Muslims with Indian heritage) and an attack on the Indian High Commission in March 2023 represent two particularly low points that impacted the bilateral relationship. With a strong Indian diasporic presence in the UK,4 it is argued that diaspora politics will impact local British politics leading to unforeseen dynamics.5 Writing on the ‘Changing Role of the Diaspora’, Gurharpal Singh notes:

“Developments in Leicester - currently the subject of two reviews - have profound implications for British domestic and international politics. They suggest that ethnic consolidation by a large migrant community with the support of transnational actors and a sympathetic ‘homeland’ government can radically disrupt local multicultural politics.” [emphasis added]

The question is: how will India and the UK choose to deal with such episodes (which in all likelihood will continue to occur)?

With substantial momentum for both India and the UK to further build their ties upon, a pressing need to diversify and grow their respective economies, a strong people-to-people bridge, and an apparent (recently-found?) ability to shed historical baggage, there are ample reasons to be optimistic about the future of the India-UK bilateral relationship. It is up to the two nations to give this bilateral relationship the due it deserves.

III. A brief transition period for the incoming (and relatively new to politics) Prime Minister Starmer:

In the reportage around the election results, two things stood out to me. The first is that Keir Starmer, the leader of the Labour Party, and now the Prime Minister of the UK, is “fairly new to politics, relatively speaking.”

Keir Starmer, named after Keir Hardie the 19th-century Scottish trade unionist who founded the Labour Party in 1900, first entered Parliament in 2015, after winning a seat in north London. Before that, he worked as a human rights lawyer for close to two decades and served as the director of public prosecutions for England and Wales for five years.

His relative newness to parliamentary politics is coupled with assertions that he is an unknown figure. An Ipsos Political Monitor survey from June 2024, found that half of those surveyed “didn’t know what Keir Starmer stands for” and “only one in five think” that Starmer (and Rishi Sunak) have “a lot of personality” [emphasis added; see Fig. 11].

A piece in The Spectator (from December 2023) noted that “actually making it to No. 10 [10 Downing Street, the Prime Minister’s office since 1735], as Starmer is expected to, without anyone knowing anything about you - that’s unheard of.” The report ended with this rather scathing line -

"They [Starmer and his team] realize that government lose elections rather than oppositions winning them, so they’re happy for the Labour leader to keep his head down and stay under the radar. Either way, if the polls are right, Britain is on course to get its most boring prime minister ever.”

In a bid to understand what Keir represents, I briefly looked up his profile and came across the following. After completing his law studies, Keir became “a barrister and worked pro bono to represent prisoners on death row in former Commonwealth countries, a role for which he is lionized in the legal profession.” Other anecdotes include the fact that he once called for the British monarchy to be abolished, was rumored to be the inspiration for the Mark Darcy character (also a human rights lawyer) from the Bridget Jones book and movie franchise, and in his law career, fought cases against McDonald’s (the famous McLibel case).

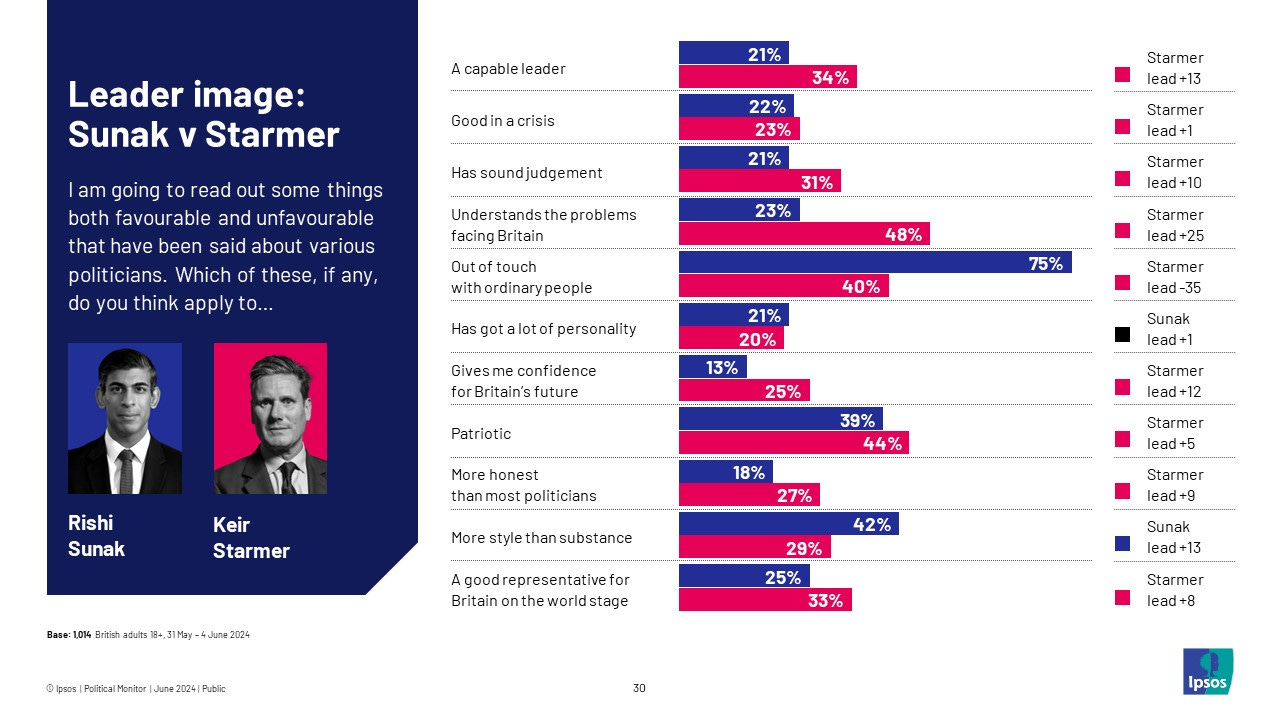

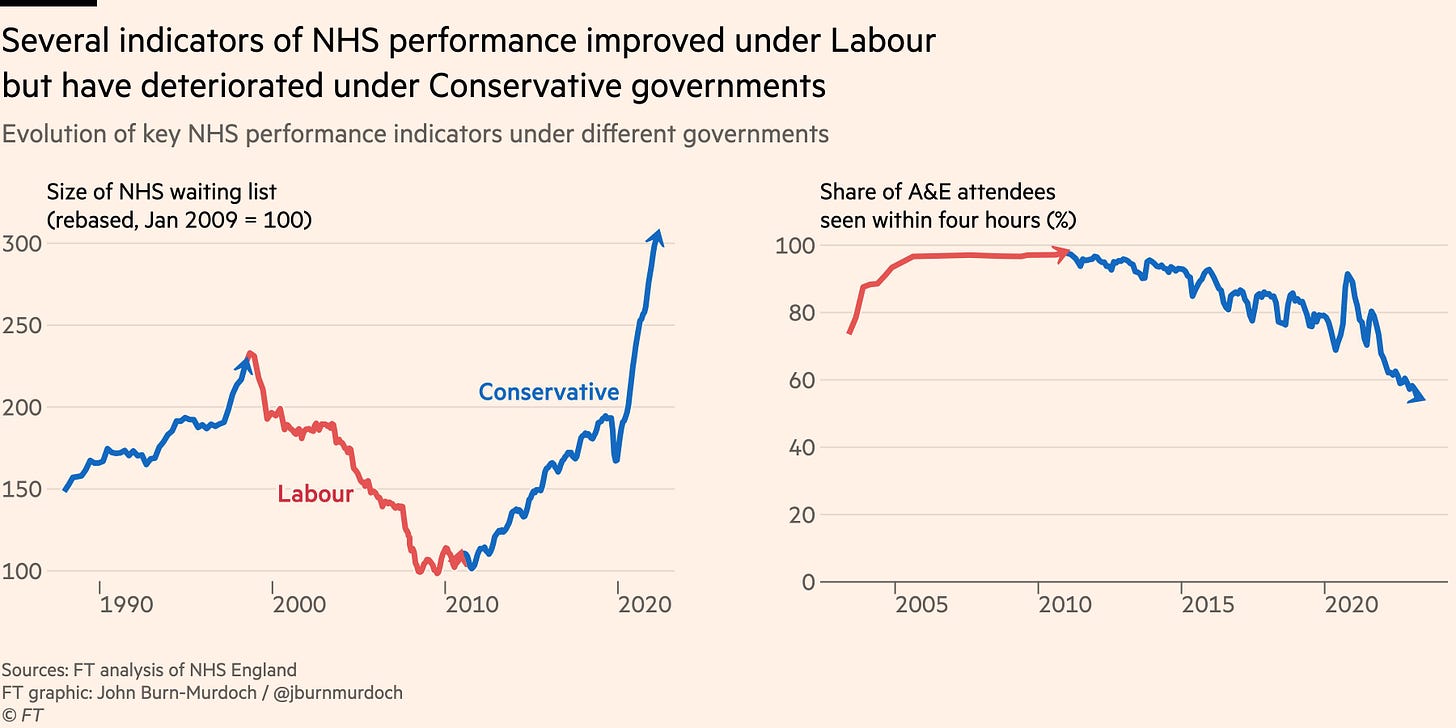

Exemplifying how the personal shapes the political, Keir Starmer’s mother was an NHS [UK’s National Health Service] nurse who suffered from a rare type of inflammatory arthritis. One of the key talking points for Starmer, and his party? To strengthen the NHS [see Fig. 12 & 13]. In an interview with the Guardian, Starmer said there “is a lot of frustration that nothing’s working [in the NHS] and it takes forever to get anything done. It’s like wading through syrup of glue.” The Labour manifesto promises to - cut NHS waiting time, expand the workforce, recruit more mental health staff, and create a ‘National Care Service’ to “set minimum standards for social care” among other steps.

The second thing that stood out to me was just how short the transition period is between the outgoing and incoming Prime Minister. The Economist notes -

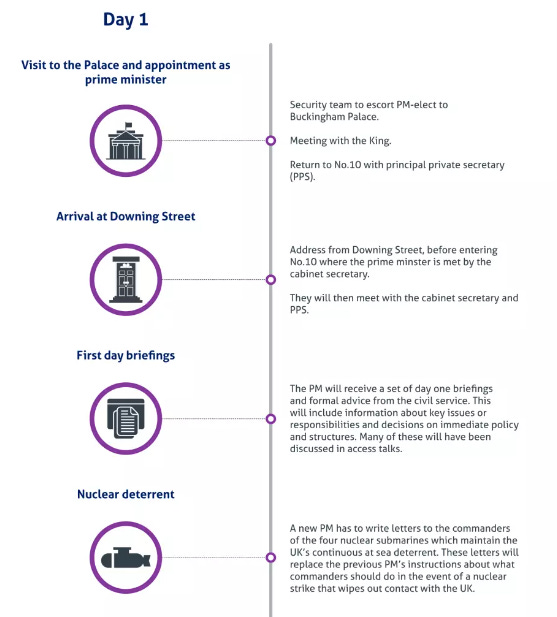

“A British prime minister’s first day is, to put it mildly, odd. If you are the French president you have a week or two to prepare for power; if you are the American, over two months. The British pm has about an hour. From the moment that an outgoing leader resigns, the incoming one begins a day that includes popping to Buckingham Palace; taking a call from the American president; moving house; and writing the “letters of last resort” in which each British pm decides what to do in the event of Armageddon. It is, says Alastair Campbell, Sir Tony Blair’s former spokesman, “a pretty stressful day”.” [emphasis added]

The Institute for Government has a very handy visual explainer of what the first day looks like for the Prime Minister [see Fig. 14].

All of this is in addition to forming the government. Catherine Haddon writes:

“The PM will appoint their cabinet ministers, typically meeting them each individually in No. 10. Any major immediate machinery of government changes will be announced as cabinet ministers are told their responsibilities. Key decisions on cabinet committees will be made at this point - including their terms of reference, chairs and membership.”

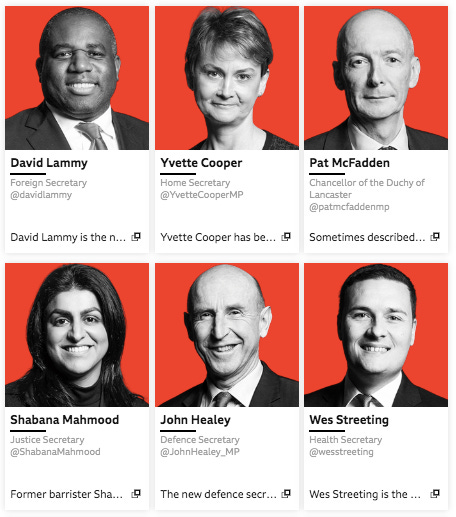

As noted above, the Keir Starmer government announced its cabinet, and July 6, 2024, marked the first full day in power. The BBC has details on the cabinet:

“The Cabinet, which was announced on Friday, saw the first female Chancellor of the Exchequer, Rachel Reeves, appointed; alongside Home Secretary Yvette Cooper and Foreign Secretary David Lammy. Although less ethnically diverse than the previous Tory top table, the Cabinet is roughly reflective of the UK as a whole, with 12% minority ethnic members including Mr Lammy. The inner circle contains 50% women, headed up by Ms Reeves and deputy PM and Levelling Up Secretary Angela Rayner, and 12% LGBT members, including Mr Streeting.”

See this BBC page to view the profile of each cabinet member [also see Fig. 15].

Further reading:

“When Left is Right” by Mukul Kesavan in The Telegraph (July 7, 2024)

“‘We’re not all Labour but everyone was jubilant: UK voters on the election result,” by Clea Skopeliti and Rachel Obordo in The Guardian (July 5, 2024)

“An Insider’s Guide to Keir Starmer’s 100-Day Action Plan for UK” by Alibhe Rea and Ellen Milligan in Bloomberg (July 5, 2024)

“Nukes and King Charles - but no door key,” in The Economist (July 4, 2024)

“The Great British Betrayal: The Rise of Britain’s Rentier Regime,” by Keith Woods in ‘Keith Woods’ substack (July 4, 2024)

“Mapping Voter Coalitions,” by John Curtice and Lovisa Moller Vallgarda in ‘Comment is Freed’ (June 23, 2024)

“Is Labour ready on foreign policy?” by Lawrence Freedman in ‘Comment is Freed’ (May 26, 2024)

‘UK-India Relations’ in the UK in a Changing Europe report, King’s India Institute (April 30, 2024)

“How "Broken Britain" might reconverge: Notes from the Economy 2030 Inquiry” by Adam Tooze in ‘Chartbook’ (December 7, 2023)

“Ending Stagnation: A New Economic Strategy for Britain,” by Emily Fry & Greg Thwaites in ‘The Economy 2030 Inquiry’ report, The Resolution Foundation (December 4, 2023)

“Britain’s New Swing Voters? A Survey of British Indian Attitudes” by Caroline Duckworth, Devesh Kapur, and Milan Vaishnav in Carnegie Endorment for International Peace (November 18, 2021)

“Tax Havens: Legal Recoding of Colonial Plunder,” by Vanessa Ogle in the LPE Project (October/November 2020)

“The Achilles Heel of Plurality Systems: Geography and Representation in Multiparty Democracies” by Ernesto Calvo & Jonathan Rodden in the American Journal of Political Science, 59, no, 4 (October 2015)

“Social Capital in Britain” by Peter A. Hall in the British Journal of Political Science, 29, no. 3 (June 1999)

I am not comparing the United States (USD 25.44 trillion GDP; USD 76,329 GDP per capita) and the United Kingdom (USD 3.089 trillion GDP; USD 46,125 GDP per capita) for the fun of it. A decade ago, in 2014, Fraser Nelson authored “Why Britain is poorer than any US state, other than Mississippi” for The Spectator and found that if the UK were a part of the US, it would be the second-poorest state (ahead of Mississippi). As John Burn-Murdoch noted in a Financial Times piece (from August 2023), since “Britain’s economy has half slumbered, half stumbled its way through the nine years since, pausing to commit occasional acts of egregious self-sabotage, the Mississippi Question has only grown more popular” [emphasis added]. Fig. 4. is from the Burn-Murdoch FT piece.

Interestingly, the two new Open General Export Licences that were published didn’t pertain just to goods and technology earmarked just for military purposes but also for (controlled) dual-use items. See: United Kingdom Strategic Export Controls Annual Report 2022, p. 67, UK Govt.

According to 2011 census data from the UK government, “Leicester was home to the largest Indian population, with 6.6% of all Indian people living there.” A UK govt report noted that “Leicester is a hyper-diverse ‘gateway’ city. It is home to many communities, particularly from within the Indian diaspora, and has a proud history of inclusivity. The civil unrest in September 2022 was widely reported in local, national and international media to be the result of tensions between young men in British Muslim and British Hindu communities with Indian heritage.” An independent review has been called into the Leicester episode and the panel will release its findings later this year.

According to 2011 census data, “there were 1,412,958 people from the Indian ethnic group in England and Wales, making up 2.5% of the total population.”

Writing about Indian politics and the Diaspore, Edward Anderson highlights how “the extent to which diasporic branches of Indian political groups have sought to influence elections outside India was underlined in the 2019 UK General Election". The OFBJP [Overseas Friends of the BJP; formally launched in the US in 1991 and in the UK in 1992] announced “that they were encouraging voters in 48 marginal constitutuences to support the Conservative Party and reject Corbyn’s Labour, on grounds connected to his historic criticism of Modi, and the party’s position on other issues relating to India such as caste discrimination and Kashmir. Starmer subsequently pledged to ‘reset relations’ in an attempt to win back Indian voters and repair relations with New Delhi.” See: Edward Anderson, ‘Indian Politics and the Diaspora,’ UK-India Relations, UK in a Changing Europe,p. 20-22.

An incredibly well-researched piece multiple relevant sources !! Absolutely fascinating.