2024 Election Watch Series (Part II): Foreign policy & Indian national elections

Summary:

Two recent incidents highlight how foreign policy issues are increasingly becoming a part of the domestic political narrative in India

The Katchatheevu controversy and allegations of India’s targeted killing program are two recent instances wherein foreign policy issues have been raised (or used) for electoral purposes

As India is expected to rise, with a polity that will be relatively richer, more educated, and more engaged with the global world, the interplay between domestic politics and foreign policy is only set to grow

Certain trends such as the personalization of foreign policy, and a more engaged Indian polity need to be examined to better understand the relationship between domestic politics and foreign policy in India

Foreign policy has (re)entered the Indian electoral chat –

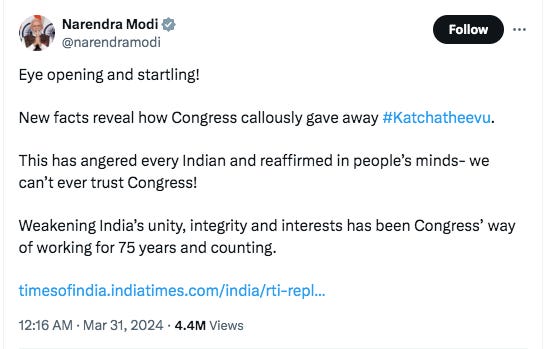

As India heads into the 2024 national elections, two recent incidents point to how foreign policy issues are increasingly becoming a part of the domestic political narrative in India. The first incident revolves around Katchatheevu, a small island located in the Palk Strait, a stretch of ocean between India and Sri Lanka. On March 31, Indian Prime Minister (PM) Narendra Modi shared an article [see Fig. 1] about the previously disputed island stating,

“new facts reveal how Congress [an opposition party previously in power] callously gave away Katchatheevu… Weakening India’s unity, integrity and interests have been Congress’ way of working for 75 years and counting.” [emphasis added]

For the uninitiated, reading the PM’s tweet, one would assume that this is an active, unresolved matter between the two neighbors. However, as Nirupama Subramaniam reminds us, bilateral agreements between India and Sri Lanka in 1974 and 1976 settled the maritime boundary. Katchatheevu was “disputed territory” that couldn’t be given up as it “was never officially demarcated as part of India.”

Subramaniam further notes –

“Importantly, from the point of view of Delhi, in return for Katchatheevu, Sri Lanka gave up its claim over Wadge Bank, and accepted Indian sovereignty over a portion of the sea off Kanyakumari. At the time, this was considered more strategic than an unpopulated island in the Palk Straits.” [emphasis added]

According to senior retired Indian diplomats, the 1974 agreement was “responsible for a subsequent improvement in relations between the two countries.” Interestingly, the Indian central government invited bids for the exploration of oil and gas blocks in January this year, including in areas around Wadge Bank for India’s energy security requirements. Crucial to note here, it was India’s 1974 and 1976 agreements with Sri Lanka that bestowed sovereign rights in Wadge Bank for India.

Given that the Katchatheevu issue was raised by the PM, and then picked up by the Foreign Minister, to target opposition political parties, the reaction from the targeted parties was swift. The Congress party accused PM Modi of “taking up the issue ahead of elections due to “desperation”.”

A media report on this incident noted –

“Opposition leaders say the BJP [Bharatiya Janata Party; currently in power under PM Modi] is trying to turn Katchatheevu – a sensitive issue in Tamil Nadu – into a controversy to gain votes in the southern state, where it has been trying hard to make inroads.” [emphasis added]

Senior retired Indian diplomats also cautioned against the politicization of resolved diplomatic issues between two countries that share friendly ties for short-term political gains. Shivshankar Menon, the former National Security Adviser (2010-14) remarked,

“The situation on the ground is hard to reverse, but such issues being raised by the country’s leadership will damage the credibility of the country and could be a self-goal by the government.”

Former High Commissioner to Sri Lanka, Ashok Kantha stressed,

“Sovereignty, and territorial integrity are not issues where the government’s position changes when there is a change in government. If the government were to reopen old agreements, it would set a bad example.”

The official Sri Lankan reaction to this controversy was measured. A Sri Lankan source told The Hindu that,

“The Ranil Wickremesinghe [the current President of Sri Lanka] administration refrained from commenting on the development, as it was a clash between two political parties in the run-up to elections. “The comments are about who was responsible for giving up the island to Sri Lanka, not about whose territory it is part of now. So there is nothing for Sri Lanka to comment on, really” an official said.” [emphasis added]

In contrast to the measured response that came from Sri Lankan officials, who recognize that the Katchatheevu issue is being raked for domestic political purposes, Sri Lankan media took a much dimmer view of the controversy.

An editorial in The Morning, a Sri Lankan daily stated –

“The recent revival of the Katchatheevu Island issue in New Delhi and its use by Indian Premier Narendra Modi to fuel criticism of his political rivals is a matter of political expediency. It risks eroding a bank of goodwill India has worked tirelessly to build in Sri Lanka since 2014, and especially since effort invested following the Covid-19 Pandemic/economic crises period…. How, sensationalizing and resurrecting settled maritime issues with their smaller Indian Ocean island nations, which help India strengthen regional maritime security is baffling.” [emphasis added]

An editorial in Ceylon Today was much sharper –

“What is interesting is that this information that PM Modi always had access to [about Katchatheevu’s status], for nearly a decade, has now been chosen to provide full transparency to the misled people of Tamil Nadu. Or perhaps there is no correlation between the BJP accusing the Opposition Congress and DMK for “callously” giving the Island away. Perhaps, them riling up in the State of Tamil Nadu, where DMK is in power, is just a coincidence as it is also a State where the BJP, not so subtly, is attempting to weasel their way in, in time for the 2024 Lok Sabha elections.”

Someone sitting in New Delhi can be dismissive of Sri Lanka media reports, especially when the official reaction from Sri Lanka has been relatively restrained. However, if one believes that public opinion on foreign policy issues matters to those in India, the same principle should apply to our neighbors (whom we strive to have friendly relations with) in the south.

The Katchatheevu incident, emerging from the domestic political discourse, demonstrates how foreign policy issues are sought to be used for domestic purposes. Another incident highlighting this phenomenon emerged following a recent report in the Guardian, which stated that –

“The Indian government assassinated individuals in Pakistan as part of a wider strategy to eliminate terrorists living on foreign soil, according to Indian and Pakistani intelligence operatives who spoke to the Guardian.” [emphasis added]

While this is only the latest in government disclosures and media reports about India’s alleged targeted killing program, the Guardian’s report is striking as it notes that –

“The fresh claims relate to almost 20 killings since 2020, carried out by unknown gunmen in Pakistan. While India has previously been unofficially linked to the deaths, this is the first time Indian intelligence personnel have discussed the alleged operations in Pakistan, and detailed documentation has been seen alleging Raw’s [Research and Analysis Wing, India’s external intelligence agency more commonly referred to as ‘R&AW’] direct involvement in the assassinations.” [emphasis added]

The Indian MEA, in response to this article, denied the allegations, reiterating an earlier statement that they were “false and malicious anti-India propaganda.” Interestingly, a day after the Guardian article came out, India’s defense minister responded to questions regarding the Guardian’s allegations by stating that –

“If any terrorist from a neighboring country tries to disturb India or carry out terrorist activities here, he will be given a fitting reply. If he escapes to Pakistan, we will go to Pakistan and kill him there.”

This statement was seen as a confirmation by some that India targeted terrorists hiding out in Pakistan. Others, such as a senior retired Indian military official, view the defense minister’s statement differently, noting that it is in line with previous statements that Indian politicians have made.

Irrespective of how the defense minister’s statement is perceived, political leaders from the ruling BJP are invoking India’s covert capabilities in political rallies. For instance, the Indian PM “alluded to operations abroad in a campaign speech on Thursday,” stating that “today’s India goes inside enemy territory to strike.”

Even in the run-up to the 2019 national elections, PM Modi, then seeking his second term, urged voters to “dedicate their vote to the Balakot air strike and to the Pulwama martyrs” referring to a devastating terrorist attack in Pulwama in the disputed region of Jammu and Kashmir in February 2019.

Examining the dynamic of foreign policy and domestic politics in India –

This isn’t the first time that an Indian government, running for re-election, is using foreign policy issues for electoral purposes. What makes the BJP’s infusion of foreign policy and domestic politics particularly striking is its nature and frequency. Suhasini Haidar, a journalist with the Hindu, raised [7:55 mins onwards] the pertinent question – “whether foreign policy issues are now entering and even dominating domestic policy discourse?”

During the 2014 national elections, there was limited focus on foreign policy. By 2019, the view was that “Narendra Modi’s success in foreign policy is credited as one of the reasons for his victory in the May 2019 Indian general election.”

Going back to the BJP’s rise to power in 2014, one can find a number of instances of foreign policy issues being pressed into action for domestic political purposes. I have previously written on this subject for instance, highlighting how one of the aims of India’s G20 presidency last year was to ‘democratize’ foreign policy. While one can draw up a list of such instances, the broader issue with examining this phenomenon is our limited understanding of how foreign policy interacts with domestic politics.

There is a need to understand this phenomenon in greater depth. Traditional thinking on this subject generally argues that the masses “have little interest in foreign policy issues”. However, as I have written elsewhere, the lack of interest or knowledge about foreign policy matters shouldn’t – and doesn’t – preclude one from having opinions.

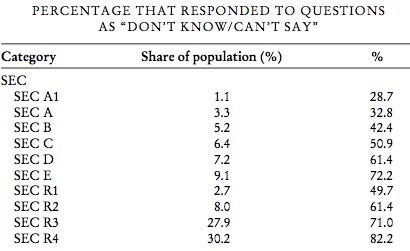

In one of the largest surveys done on Indian foreign policy attitudes, conducted by Devesh Kapur in 2005-06, the author found a link between “non-responsiveness to questions on foreign policy and socio-economic status” [see Fig. 2]. The lower down the socioeconomic ladder a survey respondent was, the more likely they were to respond to foreign policy questions with a ‘don’t know’ or ‘can’t say.’

Crucially, Kapur argues that,

“While foreign policy issues may not enjoy issue salience with the median voter, if it matters more for the marginal voter, then public opinion on foreign policy issues could become a more potent electoral issue. If India’s current economic trajectory continues, the marginal voter is likely to be urban and more educated, and if, for this demographic, foreign policy issues have greater issue salience, then public opinion will have greater weight.”

Notwithstanding the ‘if, then’ statements in the quote above, Kapur’s basic point stands. As India becomes wealthier, more educated, and engages with the outside world to a greater extent, foreign policy issues will increasingly become more entangled with domestic political issues.

Given that India is on a growth trajectory and its polity is engaging with foreign policy issues at a greater level, the relationship between domestic politics and foreign policy ought to be examined more closely. A crucial problem with this is the vast definition of what constitutes ‘domestic politics’ and as Srinath Raghavan noted more than a decade back, there is a paucity of work that study the relationship between domestic politics and India’s foreign and security policies.

While this gap in our understanding still exists, it has reduced to an extent and strides in examining this dynamic include the classification of the electoral salience of certain foreign and security policy issues, a proliferation of surveys centered on Indian foreign policy issues, and greater inquiries into the ideological underpinnings of India’s contemporary foreign policy drivers.

In a recent Foreign Affairs article, scholar Rohan Mukherjee argued that “unlike during past campaigns, India’s global role is now a central issue in politics.” He further noted –

“Barring exceptional moments, such as when India and the United States struck a nuclear agreement in 2008, previous governments treated diplomacy as a dull and specialized domain largely cut off from societal concerns. By contrast, the BJP’s rule has infused diplomacy with a sense of national purpose and transformed it into one of the key dimensions on which citizens evaluate their government. But the expansion of engagement in international relations from the elites to the masses has deeper and more predictable causes. As India rose in power, its population was bound to express a greater interest in international affairs and a greater desire for global respect and recognition.” [emphasis added]

Scholars have also noted that a key change in India’s conduct of its foreign policy is the dominant role of personality in the current political landscape. In a recent conversation, Ashley Tellis highlighting the “prominence of personality” in Indian foreign policy, argued that –

“India’s always had larger-than-life figures. You know, Jawaharlal Nehru strode the international stage. In a lesser degree, Indira Gandhi did that in her time. But I do not think we have seen before such an astute use of governmental machinery to project the personality of Prime Minister Modi, both on the domestic stage and on the international stage. I don’t think his predecessors really had that kind of political acumen to do that in a way that he has done. And so, you know, the [2023] G20 event… almost gave the impression that it was Modi’s event rather than a G20 event. I mean, he was truly the dominant personality in that whole process.” [emphasis added]

Anyone paying even remote attention to India over the past decade would be struck by the sheer dominance of the current PM on the political landscape. However, the personification of the government (usually in the mold of one individual) and its attendant impact on foreign policy is understudied in the contemporary Indian context.

One can reasonably expect that foreign policy issues will continue to occupy greater space in India’s domestic politics going forward. While one can hope for greater scrutiny into this subject, the two incidents highlighted above – Katchatheevu and the alleged targeted killing program – serve as interesting markers. These incidents are key data points in a dataset of how domestic politics and foreign policy issues interact in India.