Policy Playbook #1: India-China trade with Ajay Srivastava

Overview of the recent India-China (re)engagement debate, an interview with Ajay Srivastava (former Indian Trade Services officer) on India-China trade ties and India's trade policy, and more.

Introduction:

Recently, the debate on India engaging China has intensified. There are several threads to this. Industrialists have asked for streamlined visas for Chinese workers and are ramping up partnerships with Chinese firms, government trade officials and economists have argued for Chinese investment into India, and senior retired diplomats such as former Foreign Secretaries Shyam Saran and Vijay Gokhale (who was interviewed for this newsletter), have respectively made the case for (re)engaging China.

This debate, four years after the Galwan crisis (the worst border crisis between the two states in decades), was reinvigorated, as Tanvi Madan notes, after Prime Minister Modi said that ties with China were “important and significant” in April, alongside a range of other statements and moves by both Indian and Chinese officials.

Given the importance of the India-China relationship, I outlined the public debate around (re)engagement. To delve deeper into this bilateral relationship, I interviewed Mr. Ajay Srivastava, a former Indian Trade Services officer and founder of the Global Trade Research Initiative (GTRI). The transcript of the interview is added in the following second section. The concluding third section includes a list of the various sources I turned to, in order to better understand the India-China trade relationship and the various themes that were raised in my conversation with Mr. Srivastava, including the tech ecosystem in China, industrial policy, India-China ties and more.

I. The debate on India-China engagement:

As noted above, there are multiple constituencies to the current debate on if, why, or how, India should engage with China on the trade front. I have selected some examples that illustrate this debate.

Industrialists (successfully) pressed for streamlined visa policies for Chinese engineers and technicians because these workers were deemed critical to the functioning of domestic factories. Indian industries requested an easement in the visa process because as per them, there was a “significant skill gap” between Chinese and Indian technicians and workers. Machines purchased from China have reportedly been idle as they can’t be operated productively without Chinese technicians. According to the Indian Cellular & Electronics Association’s estimates, “the border standoff with China has cut production in the sector by about $15 billion from 2020-2023 and led to a loss of 100,000 job opportunities.” Reporting on the visa issues faced by Chinese workers, a Financial Times article quoted an Indian government official who stated (anonymously) that the Indian government was “aware China is the world’s factory” and that “it cannot be dispensed with.”

The Confederation of Indian Industries (CII), an apex trade body, put out a report on boosting manufacturing in the electronics sector where it suggested that India needs to review its trade measures with China. The CII report recommended that “India should adopt a non-restrictive approach towards investments, component imports, openness towards technology transfer in deficient areas, ease of inward movement of skilled manpower and easing of non-trade tariffs.”

The 2024 Economic Survey, released on July 22, stated that in order to “boost Indian manufacturing and plug India into the global supply chain, it is inevitable that India plugs itself into China’s supply chain.” As per the Economic Survey, given this inevitability, the choice for India is whether it does so by “relying solely on imports or partially through Chinese investments.” Roughly a week later, Piyush Goyal, the Minister of Commerce and Industry, responded to the Economic Survey’s recommendations stating that the survey is an “independent, autonomous report” and that the “Government of India has not changed its stand” on Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) from China. The Minister also added that “investment that comes from China is checked, wherever we do not feel it is appropriate, it is stopped.” As per government data, India approved “only a quarter of the total 435 foreign direct investment applications from China till June last year since the modification in press note 3 was introduced in April 2020.”

Two weeks later, in mid-August, India’s Commerce Secretary was asked about his department’s views on the recommendations that India increase FDI from China. His response? The Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade (DPIIT) “is looking into what should be the revised FDI policy and they are working in that direction” indicating a change in the government’s position. According to Rajesh Kumar, (DPIIT) Secretary, India won’t do a “full-scale opening up” to Chinese FDI, but only in cases “where the proposals are going to add value to our manufacturing ecosystem.”

Arvind Virmani, a NITI Aayog member and the former chief economic adviser to the Government noted that to reduce imports and boost local production, especially for “sensitive” products, the Government could direct Chinese companies to be in a “joint venture (JV) with an Indian company” alongside a “phased manufacturing program of some sort.”

During the 2024 Independence Day speech, PM Modi addressed external actors stating that “the development of Bharat does not mean a threat to anyone… As Bharat progresses, I urge the global community to understand Bharat’s values and its thousands of years of history. Do not perceive us as a threat. Do not resort to strategies that might make it harder for a land capable of contributing to the welfare of all humanity.” While some analysts guessed that this part of the Prime Minister’s speech was targeted towards the United States (or in another scholar’s estimation, Russia), I read this statement as directed towards China.[1]

In addition to the examples highlighted above, media reports indicate that a number of Indian companies are “striking licensing and technology transfer agreements with China’s leading lithium-ion cell suppliers.” As per a recent article, a leading Indian battery manufacturer noted that “India’s cell manufacturing industry may take “decades,” rather than “years” to reach the level of scale and technological advancement China has achieved if India doesn’t ‘de-link’ its geopolitics with what the industry needs to get cell manufacturing off the ground.” This article highlights select Indian conglomerates that have or will build on partnerships with Chinese firms. Many public commentators[2] and journalists have contributed to this debate, pushing for attracting Chinese FDI.

In this chorus of voices advocating for FDI from China, JVs with Chinese firms, and streamlined visa processes for Chinese workers, there are few voices that are arguing against the grain. Writing in the Business Standard, Ila Patnaik and Ajay Shah argued for non-tariff barriers against “Chinese exports and overseas production sites of Chinese firms.” Their rationale? They note that between 2018 and 2023, the “overall growth of Chinese exports (measured in USD) was 36%” and during the same period, their exports growth into India was 53%. Patnaik and Shah argue that India should place non-tariff barriers and other restrictions for “a finite period of time” and are only required in “areas where there is a meaningful Indian industry to protect. When the capabilities in India are very low, there is no point in incurring the adverse consequences of trade barriers.” The authors also advocate for a range of other actions to improve the functioning of Indian firms including GST reforms and liberalised engagement with other countries.

Writing about a potential ‘deal’ between India and China, Tanvi Madan highlights that even if there were to be a rapprochement, the Indian government is “bound to embark on any such outreach while keeping in mind the limits of those previous initiatives [as in 2014, 2018, and 2019], and with the understanding that there has been little let up in Sino-Indian competition across several domains.”

II. Policy Playbook #1: India-China trade with Ajay Srivastava

Given this debate on India-China ties, I felt it was important to better understand the bilateral trade relationship and India’s trade policy. To make sense of this, I interviewed Mr. Ajay Srivastava.

Mr. Srivastava is the founder of the Global Trade Research Initiative (GTRI) and a former Indian Trade Services Officer. He served for over 25 years in the Directorate General of Foreign Trade (DGFT) and in the Ministry of Commerce and Industry, was part of the team that signed Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) from 2010 to 2022 (with the exception of the 2022 India-UAE FTA, the Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement) and played a role representing India at the WTO. Since his voluntary retirement in 2022, he has been writing extensively on a variety of issues concerning India’s trade policy.

This interview is the first edition of the Policy Playbook: a series where I will speak with experts, policy-makers, bureaucrats, and others to delve deeper into policy issues that deserve nuance and greater scrutiny. This interview was conducted on August 12, has been (lightly) edited for clarity and brevity, and parts of the text (throughout this edition) are in bold for emphasis. I have included links and footnotes to provide evidence for or clarify Mr. Srivastava’s points. Views expressed are personal.

The interview:

Shreyas Shende [SS]: What is India’s China policy when it comes to trade? While reading up on India-China trade ties, I came across this piece by Ananth Krishnan, a long-time China watcher, who said that when it comes to India’s trade dependence, India doesn’t have a “coherent policy in dealing with China.” What do you make of this assertion?

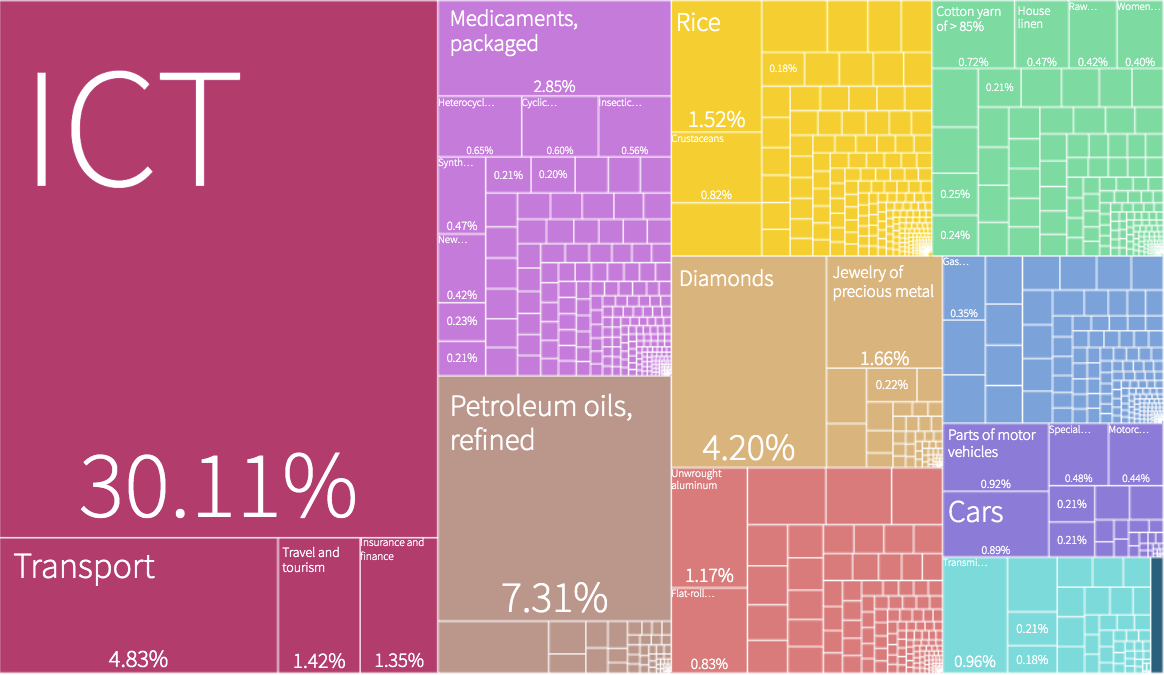

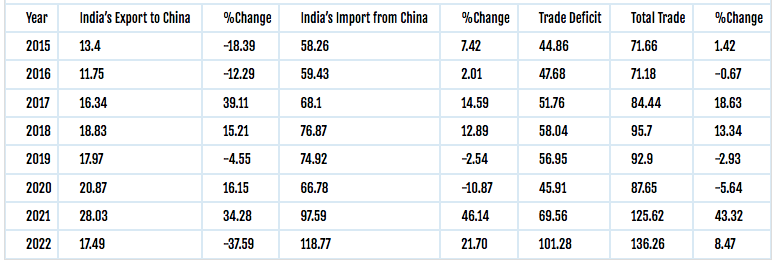

Ajay Srivastava [AS]: We can talk about this [India’s China] policy in 2-3 categories. The first is the border issue. There we are very clear, there should be no compromises. The Line of Actual Control should be where it is – no concession on that. The second is the trade issue. Our dependence on China has been increasing. I recall the time between 2003-05 when China reported its export data to India to the WTO and said India had a slight trade surplus. After that, our exports were increasing at a low speed but imports started increasing exponentially. From an almost balanced trade level in the early 2000s, now we have a trade deficit of over $80 billion in merchandise trade alone. In the past 20 years, our trade deficit has increased. From 2002 to 2022, when I took voluntary retirement, I was posted in the Ministry of Commerce. The idea was that India’s imports were not increasing because of any policy support from the government. Imports are left open, and India requires those items, that’s why India is buying. China is supplying cheaply, so we are getting those things. There is nothing China-centric about this policy. I won’t say there was any policy on promoting imports. Imports were coming because we were open [to them] and we needed those things. If you study the import profile of the products coming from China to India, they don’t send agricultural products or raw materials. It is mostly intermediate products, capital goods, and machinery. So out of $101.8 billion worth of imports from China in this fiscal year 2024, $100 billion are industrial imports. Industrial imports include items such as machinery, electronics, auto components, etc. If we further divide industrial products into 8 sub-categories, say electronics, machinery, leather, garments, etc… I was shocked [to learn about India’s dependence]. The general impression in India is that our dependence on China is too much in the electronics sector and we have to make efforts to bring it down. I realized that China is a leading supplier to India in each of these sub-categories [see Table 1], not just for electronics. Our imports from China for textiles are low, but even in that category, China is the top supplier. Overall, if we talk about India’s industrial imports, then China’s share is 30%.

SS: You authored this interesting Hindu Business Line article after the 2024 Economic Survey came out. You pointed out, as you did above, that there was a period in 2003-05 when we had equal trade. You noted that India even had a small trade surplus with China during this period. Now, the situation is drastically different where India is exporting $16.67 billion worth of goods and importing $101.8 billion worth of goods [as of FY2024]. Clearly, there are multiple factors responsible for the massive trade deficit. What contributes to this?

AS: If we forget about exports for a minute, and focus only on imports… USA, Japan, and South Korea have similar levels of import dependence on China. What is better for Japan or South Korea is that their exports are also on the higher side [see Table 2]. In our case, India and China's production profile is almost similar, except for the electronics sector [see Fig. 1 & 2]. Our exports have not increased, but because of our industrial expansion, we get a lot of machinery and chemicals from China. This is the basic reason for the trade deficit. On import dependence on China, we have a similar share as those of the USA, Japan or South Korea. We are falling short when it comes to the export share. Japan and South Korea’s exports [to China] are on the higher side. Our exports have not picked up because we produce a similar category of commodities and products as China. Of course, it also has to do with Chinese policy. The Chinese strictly control what can come into their country, with non-tariff barriers, registration requirements, etc.

SS: Of the many issues that ail the India-China trade relationship, a key one is market access. For instance, the Ministry of Commerce released the ‘Foreign Trade Policy Statement’ in 2017 that said India has more than 500+ US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved pharmaceutical units, yet “high-quality products from India face routine rejection in China and many other countries.” Another example was in the IT sector. There’s this report that highlighted how NIIT is the only successful Indian IT company in China, which “isn’t selling Indian IT services or products, but training tens of thousands of young Chinese in IT skills every year.” Given that the issue of market access has been on the radar for years, how do you make sure Indian firms get greater levels of access in different markets?

AS: Indian pharma imports 70% of its API requirements from China. With biosimilars,[3] the import dependencies are 85-90%. So basically, we buy raw materials from them, add value, and then export them everywhere. China, which makes APIs and biosimilars, can easily make formulations for their own use. They don’t need [Indian pharma]. So I don’t buy into this conspiracy theory, about pharma [and market access]. Of course, the Chinese use non-tariff barriers, but I do not agree [with the point about market access] for the pharmaceutical sector. For IT exports, we have to recall that the Chinese don’t allow the likes of Google, Facebook, etc in their own country. They want to make a separate world in the IT domain. I think that paranoia leads them to do everything on their own, even if it is at a lower scale or in a more expensive way. The Chinese want to control all aspects of the IT sector.

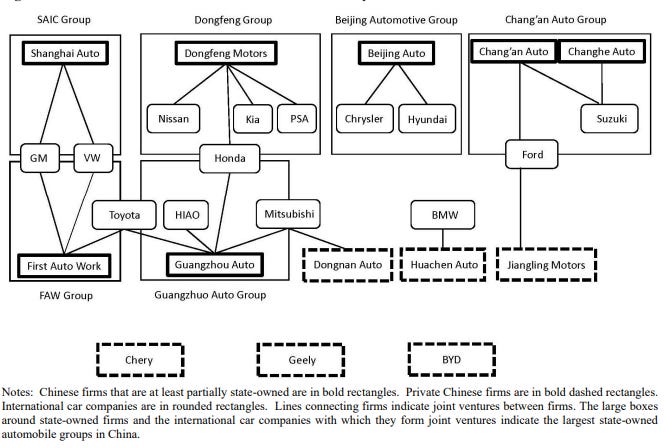

SS: In one of your articles you pointed out how certain Chinese companies are forming joint ventures (JVs) with Indian companies. I recently read a report about a potential JV between Mahindra and a Chinese automobile firm. I tried to get data on foreign collaboration in the Indian industry, and found this set of RBI surveys on ‘Foreign Collaboration in Indian Industry’.[4] China wasn’t mentioned even once in these surveys as a country that enables tech transfers. It is usually Japan, the United States, Germany, South Korea, and other European countries that enable tech transfers [see Fig. 3 & 4]. When there are JVs with Chinese companies, what is the scope of tech transfers or knowledge sharing? Can, and should, India emulate the practice of getting foreign companies to form JVs [5] and institute tech transfers and knowledge sharing the way China did [see Fig. 5]?

AS: [Tech transfers and knowledge sharing] will work only when the two countries have some FDI being transferred. Tech transfers are parts of a FDI package. However, from March 2000 to the current time, China is at number 37 in India’s FDI suppliers. In all these 24 years, the total FDI received from China is about $3.5 billion – which is nothing.[6] So there has been no FDI transfer [from China]. What is happening now is that China is getting rebuffed in U.S. and European markets [see Fig. 6]. These Western markets are saying no Chinese products. So China knows that if they export to Europe or America, there might be some problems. So Chinese companies are now forming JVs in different Southeast Asian countries, including Indonesia, Thailand, and Malaysia [see Fig. 7]. Chinese companies are also approaching India for investments. Chinese companies will use these countries as a base to export to the world. This is the Chinese plan. Following these plans, they set up plants in Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, and Vietnam but in 2024, the US put tariffs on solar panels produced by Chinese companies in these Southeast Asian countries saying that since we are banning Chinese exports, then how come China is using these countries as a base.[7] Chinese companies were also eyeing Mexico, to produce cars for the US market. Mr. Trump, in March 2024, said that he is watching this development and that he will not allow such cars to be imported into the United States.[8] This is the background of what is happening around India’s neighborhood, in Southeast Asian countries. Forgetting all these experiences, in India, the Economic Survey, for the first time explicitly mentioned that India should welcome FDI from China. On this, there are a few things [to keep in mind]. If you are welcoming [Chinese FDI], will they come here? If they come here, will they thrive here? If they are able to make [products] here, will the US or EU accept these products? So there are a lot of ifs and buts, and this issue hasn’t been debated thoroughly. I wrote a piece that hasn’t been published yet where I say, ok let us assume that I have welcomed Chinese FDI, as said by the Economic Survey. Now, let me put myself in the shoes of a Chinese investor who has set up shop in India. What issues will he face while manufacturing in India and while exporting? I don’t find any encouraging signs that this endeavor will succeed in India.[9]

SS: In this ‘Core Report’ podcast interview, you pointed out that a lot of goods that India imports from China are not actually high-end products. They are low-level products that could be produced in India if there was the will. You recommended ways in which India can cut imports from China, and I will point out two of them. The first was reverse-engineering low to medium-technology goods, and the second was making long-term commitments in deep manufacturing. Can you briefly expand on this, and add any other policy recommendations you may have to cut imports?

AS: We need to understand this part very deeply because India has been making policies and spending lakhs and lakhs of crores of rupees for the past 15 years to become better at manufacturing. I don’t see we are succeeding. Small successes are there, but genuinely, I am not happy with those. We need to do more. If you study how Japan or South Korea grew post WWII or China in the 1980s, they opened up machinery [that they imported]. Japan focused on the auto sector.[10] They were buying good cars from Europe or America, opening them, reverse-engineering them, putting their best minds, and reassembling the products at a better scale, at half the price. They then started exporting it back to the same Western countries. Japan focused on autos, electronics, and, robotics. South Korea focused on electronics initially and then expanded to 2-3 more sectors.[11] South Korea also used the same tactics [as Japan] but they also focused on R&D. South Korea also started promoting some big firms, irrespective of the cost. China did the same thing as well. I was studying how China did so well in electronics in 1995. The Chinese were not making anything back then. For example, in the 2000s, Apple decided that they would make their wares in China. More than a thousand Apple engineers were stationed in China for years.[12] They handheld Chinese workers. Initially, the Chinese were importing everything and they would only assemble. Then, gradually, the Chinese grew from there. So reverse-engineering is a great way,[13] unless it is truly very high-tech. Take the example of car engines. It is a mechanical thing. You just open it, and your auto engineers should be able to make out [the mechanics inside] and at least replicate it. Within 6-8 months, the engineers can perfect a prototype of most of the things like pumps, compressions, etc. We say, the making cost for Indians is $100 and the Chinese are supplying it at $70 so why make it here? No, no, no. I was studying how the Chinese make solar panels. The average subsidy in China ranges from 35% to 70% and every fifth firm is non-profitable [see Fig. 8].[14] Still, these Chinese firms survive and send their goods to the whole world based on government support.[15] The Chinese government is very smart. They will stick to a few sectors and when everybody else [non-Chinese] shuts down, the Chinese government will remove the subsidy and the original price will remain. So, when somebody says prices are higher in India – I say select 20 products. Forget about the prices. Perfect making these 20 products. We can talk about the price of the product after five years. So that’s the way every country has grown. I am not talking about something new here. Japan, South Korea, China, everybody has grown this way. We have to do the same thing. Instead, we want quick fixes. This is why, we are importing everything and putting it in a box and sending it as a ‘manufactured’ product. That’s not manufacturing. That’s increasing our dependence on countries like China.

SS: With the examples that you pointed out – China, South Korea, Japan – a lot of these countries had (or have) substantive industrial policies. Mariana Mazzucato, for instance, has written about how governments can take risks, create value, and at times pick winners. Is this something that you think is recognized and acknowledged by the various constituencies invested in India’s growth story – the government, industry, policy-makers, and others?

AS: All these ideas about deregulation, no intervention from the government, and market forces, came from the U.S.A.[16] These are very beautiful ideas that appeal to our logic. But why did these ideas come from the U.S.A.? I dare say, that the United States decided in the late 1970s and early 1980s that they are going to stop manufacturing most things,[17] except high-tech goods [see Fig. 9]. They didn’t want to dirty their backyard and they wanted to shift manufacturing, including to China for the most part. That’s why Henry Kissinger was making those frequent visits to China.[18] So when a country decides it doesn’t want to manufacture, a lot of investment is made into research in a particular direction – namely that deregulation is good and no government support is needed. WTO wouldn’t have achieved so many results in lowering tariffs and other barriers unless it was pushed by the United States, the EU, and some other nations. They thought tariffs were bad and while they were arguing about these things and shifting their investments, expertise, and firms to manufacture in China, China was thinking long-term. The Chinese knew that to become the factory of the world, some higher level of support was very much needed. Individual firms can be very large – they cannot survive the big market forces. So, the Chinese started giving them subsidies. They started making national champions. Not just one or two national champions, but hundreds and thousands of such champions.[19] They selected certain sectors like EV, solar, and green tech, and they excelled in those sectors. Why? The United States facilitated international trade flows by first arguing that deregulation and lower tariffs are good, and then using the WTO, where [other member states] negotiated and brought down their tariffs. This increased world trade flows, especially from China, and other countries including India. Everybody benefited from this [increased trade flows]. So, the United States thought that China would develop this way, and the U.S. would get rid of its pollution problem by shifting manufacturing to China. I was digressing to give you this view [into U.S. policies, increased trade flows, and lowered tariffs] but no country can develop high investment functions like manufacturing without long-term support. If a particular firm does this [invest in manufacturing], with deep pockets, they will turn into monopolies. That is bad for the country. So China never goes for monopolies.[20] They create 10 large firms in a particular sector. In the solar sector, there are at least 200 firms in China. In the auto sector, there are more than 200 automakers that are world-class suppliers to the world. If I want to summarize, I’ll say that government interventions are a must. Initial governmental support is a must. But, we [the Indian government] should only support those firms where in a few years’ time, these firms are ready to fly on their own wings, without government support.

SS: You pointed out that government intervention is a must. We know that China identified strategic high-tech and emerging sectors and designed industrial policies around the same. The Indian government also launched its version of industrial policy through the Production Linked Incentives scheme (PLI) where 14 sectors were targeted. Some have questioned the rationale behind focusing on sectors like toys or white goods. Mr. Subhash Chandra Garg, the former Finance & Economic Affairs Secretary, argued that the PLI in its current form is “thinly spread” making the scheme a “messy affair.” He also critiqued plans for potential new PLI schemes in non-tech industries like toys or footwear instead advocating for focused interventions in strategic, high-tech industries. What is your sense of this?

AS: I have written a lot on this subject. I will never support production-linked incentives for sectors that have hundreds or thousands of firms. The toy sector has thousands of firms. Shoes have thousands, maybe lakhs of firms. What happens in these cases is that there are no horizontal incentives. Horizontal incentives are those that are available to everybody. Suppose 100 firms are making shoes in India and I give PLI to two firms. Even though shoes are of the same quality more or less, those two selected firms will have better market access, because they can sell their shoes in a cheaper way. What will happen to the other 98 firms? Why are we harming the other firms? So PLIs should be for new, strategic, narrowly defined sectors where there is not much [existing, indigenous] expertise. We should borrow foreign expertise, invite Indian and foreign investment, and focus on sectors where there aren’t many people [or firms]. If there are many firms, we will end up hurting those who haven’t gotten PLI.

SS: I want to ask a bit about your professional experience. You were previously an Indian Trade Services officer and played a role in many FTAs (including in the India-Japan FTA). Looking back, what were some of the key challenges you faced while working on India’s trade policy issues, and some successes that you were a part of? I would appreciate an insider’s look into what it is like being an Indian Trade Services officer.

AS: The best part of my experience is that trade is a game played by very few people in India. For example, there are about 50,000 exporters who do about 90% of merchandise exports from India. Only 50,000. And in my more than 25-years of government service, I must have met at least 40 to 50% of these exporters. Why these exporters come to a government official is a sad part. In an ideal position, these exporters should not have to come to government officials. Because I was in the trade services for a long time, I was involved in trade policy-making which basically included how to incentivize local firms to export more to different markets, negotiating FTAs, and [representing India] at the WTO. I was involved in almost all the trade agreements [that India signed from 2010] till 2022, except for the agreement with the UAE. Our team [at the Indian trade services] size has always been very small[21]… I would not like to answer the question about successes. Some other day perhaps.

SS: Thank you for your candor. This recent Financial Times article on India-China trade cited a ‘split’ within the Indian government when it comes to trade policy with China. The Ministry of External Affairs and the Home Ministry had a much more hawkish stance, whereas the economic technocrats argued for much more flexibility in India’s approach. Given your time at the DGFT, can you shed light on how some of these conversations [between national security concerns and economic imperatives] played out?

AS: [Two decades back] relations with China were pretty normal, and of course, we were worried and secretly jealous of the Chinese. This is because our imports were increasing but exports weren’t. Things worsened post-Galwan. Before 2020, we didn’t have a separate policy restricting anything from China. Galwan changed everything. Before 2020, we were treating China at par with any other country, there was no discrimination. This can be seen in the increasing imports from China, there were no restrictions. We always thought we had to improve our domestic manufacturing to catch up with the Chinese. Galwan changed everything and the government said that any investment from bordering countries, including China, needs to be screened.[22] We became more security conscious. That is when the MEA and the Home Ministry were playing a role. While these things were talked about [India’s trade relations with China against a deteriorating security environment], investments were screened and while many [Chinese firms] were disallowed, imports continued unabated. Imports [from China] were increasing year on year [see Fig. 10]. On the economic side, we didn’t do any harm to imports from China because we thought we needed them [imports from China]. There is a realization that we need to do our homework to cut imports from China, but there were no explicit measures to cut imports. The perception changed on the security level but trade continued unabated.

SS: For people who are looking to understand and study India’s trade policy, what are some areas that you think scholars, especially young researchers, should study more? What aspects of India’s trade policy deserve greater scrutiny? Basically, research that would aid the Indian Government in solving some of these thorny trade-related issues.

AS: There is very little serious scholarship on India’s trade policies. Very little. If you read the works of reputed economists, you will see predictable prescriptions, which include ‘tariffs are bad’ and ‘open the borders.’ Beyond this, there is very little. I don’t agree with these arguments. Visualize a scenario where the ease of doing business is very bad in your country, and you remove the tariffs. Then whatever little manufacturing is happening will be swamped by imports. So we have to work on both areas – while we cut tariffs, we should work even more diligently on making it simpler to do business in India. The first focus should be on studying the ease of doing business in India. That should go beyond the rhetoric. The World Bank will decide to measure this [ease of doing business] and make 3-4 categories and give marks. This isn’t enough. The best way [to study ease of doing business] is to speak to people at the managerial level who handle actual transactions. For example, I spoke to a few people in the garments sector. I didn’t know much about the sector but I was amazed … when you talk to the person who handles licenses, goes to the ports, deals with customs, learn what problems they are facing. We have to study these things. Map these processes. This hasn’t been done at a serious level. Academics follow a template that has become old. You will find papers with complicated equations but nothing new in the conclusions. You may find me to be cynical but you are a young person so I can say all these things.

SS: Thank you for your time, I really appreciate it.

III. Further reading:

To prepare for the interview (Mr. Srivasta was extremely generous with his time and expertise), and understand some of the India-China trade dynamics and questions around industrial policies (including Chinese policies), I referred to a variety of sources. I have highlighted some of the works I referred to below (organized thematically and chronologically) in case any Indialog reader would like to dig deeper into these issues.

China’s tech ecosystem:

A Chinese tech executive told Lawrence Kuok “at first I was only going to copy you [western tech firm], but now I’m going to crush you.” Kuok argues that “Chinese tech companies would crush Facebook, Twitter, and Google in China even if those foreign companies weren’t banned.” [March 23, 2018]

In 2018, an explosive article in The Intercept reported that Google was building a “censored version of its search engine in China.” Following heavy backlash from “human rights activists and some Google employees” and a call by then U.S. Vice President Mike Pence to drop the project, dubbed ‘Dragonfly, the tech giant suspended the program. Matt Sheehan, writing about Google’s parlay with the Chinese government (the company first entered the Chinese market in 2006, and was there till 2010 when it was “abruptly pulled” after a “major hack of the company and disputes over censorship of search results”), argues that back in 2006 the thinking was “Google wanted to be in China” but “China needed Google.” Given the sea-change in China’s tech ecosystem, this logic doesn’t hold anymore. [December 19, 2018]

Interesting insights into the “red vs. expert” debate in this Macropolo research piece, ‘The Return of the Technocrats in Chinese Politics’ by Ruihan Huang and Joshua Henderson. The authors note that “Deng [Xiaoping], like the leaders who succeeded him, believed that nation-building required domain expertise and technical chops, not just pure-bred CCP politicians” and that “Beijing has given more political power to technocrats to execute ambitious industrial policies and build out local tech supply chains.” [May 3, 2022]

In this Financial Times article, Patrick McGee documents how Apple ties its fortunes, and rise, to China, noting that the company built a “supply and manufacturing operation” of intense complexity and depth, embedded its “top product designers and manufacturing design engineers” in “suppliers’ facilities for months at a time,” spent billions on “custom machinery to build its devices,” and received support from Chinese government spending in the form of “preferential policies including important tax-exemptions, as well as apartment complexes to house migrants, warehouses, highways and airports.” [January 17, 2023]

CSET policy brief on ‘China’s Technology Policies and Ecosystem’ authored by Owen J. Daniels. [September 2023]

Rhodium Group research note on ‘China’s Science and Technology Spending in an Economic Slowdown’ by Camille Boullenois, Agatha Kratz, and Laura Gormley. [December 15, 2023]

China & Southeast Asia:

This IMF paper on ‘China’s Changing Trade and the Implications for the CLMV [Cambodia, Lao P.D.R., Myanmar, and Vietnam] Economies’ pointed out how these countries had one thing in common – “they are all open economies that are highly integrated with China.” The paper also has a great primer on the evolution of China’s trade structure, its move up the value chain, and Vietnam’s rise. [2016]

This Economist article from April 2024 tracks how Chinese firms are expanding in Southeast Asia, and notes that “Chinese firms sometimes bypass these restrictions [controls placed by the Trump and Biden administrations on products made in China] by moving factories to countries in the region.” According to the estimates of one Chinese businessman in Hanoi, “40% of factories in northern Vietnam are now Chinese-owned” and “annual foreign direct investment from China to Indonesia, Malaysia, and Vietnam hit $8 bn in 2022, quadruple the amount a decade earlier.” [April 25, 2024]

An HSBC survey from November 2023 found that “Southeast Asian businesses are especially interested in expanding their supplier networks in China: 92% of Indonesian businesses, 87% of companies from the Philippines, and 89% of those from Vietnam are expecting supply chain growth in China over the next three years” and “some 65% of China-based firms had plans for inorganic growth in ASEAN in 2023 or 2024.” [May 19, 2024]

China’s auto sector:

Jie Bai provides a brief overview on the drivers of the Chinese car market. [Summer 2022]

Bai, Barwick, Cao, and Li’s NBER paper on ‘Quid Pro Quo, Knowledge Spillover, and Industrial Quality Upgrading: Evidence from the Chinese Auto Industry.’ [November 2022]

‘China’s automotive odyssey: From joint ventures to global EV dominance,’ by Yueyuan Selina Xue, Wei Wei, and Mark J. Greeven for IMD. [January 26, 2024]

Kevin Xu profiles Wang Chuanfu, the founder of BYD, and notes that to break into the battery manufacturing space, “Wang reverse-engineered the manufacturing process, broke it down into small pieces, then hired very cheap human labour” and that “Wang’s penchant to reverse engineer, would feature more prominently later” when BYD “decided to make EVs.” Xu writes, “to learn how to make cars, he [Chuanfu] bought 50 or so second-hand cars from all the best foreign brands, took them apart, and learned how to make cars – a tale he has been fond of sharing in interviews since.” [February 8, 2024]

John Letzing and Minji Sung map the rise of China’s autos and other global trade trends in this World Economic Forum note. [February 9, 2024]

Responding to a Financial Times article that noted that “German direct investment into China has risen sharply this year (2024), in a sign that companies in Europe’s largest economy are ignoring pleas from their government to diversify into other, less geopolitically risky markets,” Adam Tooze in his newsletter reminds readers that not only is China the “largest car market” (since 2008) and that “rebalancing from China may reduce your risks in the event of war with Taiwan” but if you leave the Chinese market “it substantially increases the risk that you do not stay on pace with the trends in the world’s leading market. It increases the risk that you get blindsided by competition you did not see coming.” [August 14, 2024]

A recent China Daily report highlighted how the Chinese auto sector has boomed – 469,000 vehicles were shipped overseas in July 2024, up 19.6 % year-on-year according to the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers). An expert from the Development Research Centre of the State Council noted that as Chinese carmakers transform into global companies, they will “build manufacturing facilities overseas.” Key markets include Southeast Asia (BYD, Neta, and Aion have established plants in this region) and Central Asia. [August 19, 2024]

An Economist article on how Baidu, Huawei, and Xiaomi have “built thriving auto businesses.” [August 21, 2024]

Industrial policy & Chinese policies:

Margaret M. Pearson’s ‘The Business of Governing Business in China: Institutions and Norms of the Emerging Regulatory State’ in World Politics. [January 2005]

Barry Naughton’s ‘China’s Distinctive System: Can it be a model for others?’ in the Journal of Contemporary China. [April 28, 2010]

NBER working paper on ‘China’s Industrial Policy: An Empirical Evaluation’ by Barswick, Kalouptsidi, and Zahur. [July 2019]

CSET’s translation of China’s ‘National 13th Five-Year Plan for the Development of Strategic Emerging Industries.’ [December 9, 2019]

UNCTAD paper on ‘China’s Industrial Policy: Evolution and Experience’ by Wei Jigang. [July 2020]

Mariana Mazzucato’s Mission Economy: A Moonshot Guide to Changing Capitalism. [January 28, 2021].

Allan, Lewis, and Oatley’s ‘Green Industrial Policy and the Global Transformation of Climate Politics’ in Global Environmental Politics. [November 2021]

The 2022 CSIS report by DiPippo, Mazzocco, Kennedy, and Goodman, ‘Estimating Chinese Industrial Policy Spending in Comparative Perspective’ has details on the various mechanisms the Chinese state uses to support its growth, along with a comparative assessment of how this spending stacks up against other major economies including Brazil, France, Germany, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and the United States. [May 2022]

VoxEU column by Lee Branstetter and Guangwei Li arguing ‘The actual effect of China’s “Made in China 2025” initiative may have been overestimated.’ [August 11, 2023]

Kyle Chan’s primer on “managed competition” in Chinese state firms from his excellent ‘High-capacity’ newsletter (where he highlights key points from his Chinese Journal of Sociology article ‘Inside China’s state-owned enterprises: Managed competition through a multi-level structure’). [June 21, 2024]

India-China ties (trade & security) & India’s policies:

Journal article on the ‘Sino-Indian Boundary Dispute, 1948-60’ by Srinath Raghavan for the Economic & Political Weekly. [September 9, 2006]

Study report on ‘India-China Bilateral Trade Relationship’ prepared for the RBI by S. K. Mohanty. [January 2014]

Report tracking ‘Chinese Investments in India’ authored by Amit Bhandari, Blaise Fernandes, and Aashna Agarwal for Gateway House. [February 2020]

Brookings India report by Ananth Krishnan, ‘Following the Money: China Inc’s Growing Stake in India-China Relations.’ [March 2020]

‘Press Note 3’ released by DPIIT in 2020, reviewed the government’s FDI policy to curb “opportunistic takeovers/acquisitions of Indian companies due to the current COVID-19 pandemic” and revised its position to state that “an entity of a country, which shares land border with India or where the beneficial owner of an investment into India is situated in or is a citizen of any such country, can invest only under the Government route.” [April 17, 2020]

Matt Sheehan analyses the potential consequences of India’s ban against a slew of Chinese apps (following the Galwan clash) and explores parallels “to see if China’s internet controls provide any lessons for India.” [July 23, 2020]

Paper on the ‘Future of India-China Relations’ after Galwan by Vijay Gokhale for Carnegie India. [March 10, 2021]

Note on why India and China are unlikely to reach a ‘Strategic Détente’ by Saheb Singh Chadha for Carnegie India. [August 29, 2023]

Transcript of Tanvi Madan’s ‘Global India’ podcast episode with Ashok Malik on ‘India’s economic ties with China: Opportunity or vulnerability’ for the Brookings Institution. [November 15, 2023]

C. Raja Mohan argued that India should “stay the course with its current approach to China” and not rethink its policy of resuming “political and economic dialogue with China until the military confrontation in the Ladakh frontier, which began in the spring of 2020, is resolved to its satisfaction.” [November 22, 2023]

Fascinating ground reportage on Foxconn’s experiences in establishing a plant in India to build iPhones by Viola Zhu and Nilesh Christopher for RestofWorld. [November 28, 2023]

Report on ‘India’s Growing Industrial Sector Imports from China’ by Ajay Srivastava for GTRI. [April 29, 2024]

NITI Aayog’s head called for “reforms in India’s tariff policy, including lower tariffs and ease of procedures for it to be meaningfully included in the global value chains (GVCs).” He said, “India is not a part of GVCs in any significant way and to get into GVCs means a fundamental change in a lot of things. It means low tariffs and low procedures. Things have to move smoothly, seamlessly across borders. There has to be a concerted effort to make India part of GVCs. We look back and get very happy about our performance. But if you look left and right, you see our performance can be much better.” [May 17, 2024]

In this edition of ‘Anticipating the Unintended,’ the authors assert that the 2024 Economic Survey engages in ‘plain speak’ on the state of India-China ties, and the policy options available to the Indian Government. [July 28, 2024]

In this article, Ashoka Mody highlights lessons from East Asian economies: “East Asian economic history teaches us that foreign knowledge is pivotal but spurs development only when combined with adequately educated domestic workers.” [July 30, 2024]

The DPIIT Secretary, in this interview, lays out the government’s thinking on FDI from China, how policies can support Indian labour, and low disbursements in the PLI scheme. [August 3, 2024]

This report highlights how a Chinese government policy on eSIMs (virtual SIMs) impacts the pace of adoption of eSIMs in India. [August 5, 2024]

Ajay Srivastava methodically goes through every argument put forth in the ‘Economic Survey 2024’ in this article: “India should welcome Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) to boost manufacturing, increase exports, reduce imports from China, and strengthen our role in global value chains (GVC).” He then asks if “the promised gains to manufacturing, exports, imports, and GVC actually happen?” On every count, the answer is not as straightforward as portrayed by the Survey. [August 15, 2024]

Vipin Sondhi and Rajendra Srivastava’s article on ‘Why being a product nation helps.’ [August 21, 2024]

FAQ on India’s FTAs by the Ministry of Commerce and Industry.

Other:

Hausmann, Hwang, and Rodrik’s paper ‘What you Export Matters.’ [October 2006]

McKinsey article on ‘How China country heads are coping’ amidst signs of weak growth in China in 2015 by Wouter Bann and Christopher Thomas. [October 1, 2015]

Amiti, Dai, Geenstra, and Romalis’ NBER paper on ‘How Did China’s WTO Entry Affect U.S. Prices?’ [December 2018]

Yuen Yuen Ang’s China’s Gilded Age: The Paradox of Economic Boom and Vast Corruption. [May 2020]

Kim, Lee, and Shin’s NBER paper on ‘The Plant-Level View of an Industrial Policy: The Korean Heavy Industry Drive of 1973’ in NBER. [September 2021]

Macropolo research note on ‘Supply Chain Diversification in Asia: Quitting China is Hard’ by Rita Rudnik. [March 31, 2022]

Speech & presentation on ‘Global value chains under the shadow of COVID’ by Hyun Song Shin for the Bank for International Settlements. [February 16, 2023]

Data & charts on the US-China trade war by Chad Bown for the Peterson Institute for International Economics (updated till April 2023). [April 6, 2023]

Chen and Evers’ International Security article on “Wars without Gun Smoke: Global Supply Chains, Power Transitions, and Economic Statecraft.” [October 2023]

Richard Baldwin points out that China is a manufacturing superpower in this VoxEU article. [January 17, 2024]

United States Trade Representative report on ‘China’s Acts, Policies, and Practices related to Technology Transfer, Intellectual Property, and Innovation.’ [May 14, 2024]

‘A Diversification Framework for China’ report by Rhodium Group’s Agatha Kratz, Daniel H. Rosen, Camille Boullenois and Juliana Bouchaud. [August 7, 2024]

[1] Amb. Shivshankar Menon, the former National Security Advisor of India, argued that “Since around 2016, the Chinese have been saying that India is no longer non-aligned or neutral, meaning that we have gone over to the dark side, to the USA. In fact, one motive for what they did, moving across the line in several places in the western sector in 2020 and preventing us since then from accessing patrolling points that we had visited for years before that, was probably to show the US that India is no counterweight to China, and to show India that the US cannot solve out China problem.” One could very well argue that China has attempted to thwart India’s rise by running roughshod over bilateral boundary agreements and through its maneuvers along the border in 2020, forcing India to spend more resources on managing its security environment.

[2] It is important to evaluate the logic for each of these arguments. Here I have examined one such piece that advocates attracting Chinese capital: In his Times of India column Swaminathan Aiyar makes a case for Chinese FDI to India. He invokes the American ‘high fence, small yard’ argument as an example of how two countries can engage economically, carving out space for certain restrictions, despite persistent security tensions. This argument can be contested for the following four reasons. Firstly, the very premise of a ‘high fence, small yard’ can be questioned (see this set of responses to U.S. National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan’s speech at the Brookings Institution in 2023 where Sullivan reiterated the ‘small yard and high fence’ approach; also see this succinct deck on U.S. export controls and policy by the Bureau of Industry and Security). This CSIS report on export controls on U.S. chips to China demonstrates how the “Western “fence” is currently full of holes, not least because of the lack of full congruence between U.S. and allied export control regimes.” For the folks at CSIS, the “concept of a “small yard, high fence” must be regarded as aspirational and certainly not a near-term reality.” This Rhodium Group note highlights the inherent tensions in U.S. policy when it comes to its ‘small yard, high fence’ approach. A second, and related, point is that even if the premise of the ‘small yard, high fence’ were to be assumed, can a state ensure that the yard is small, and the fence high enough? One only has to look at the difficulty the United States is facing in ensuring this. The U.S., with all of its state capacity, finds it difficult (for very good reasons) to strictly enforce its restrictions and export controls. Following President Trump’s 2019 ban on the delivery of certain goods and services to Chinese firms without export licenses, the United States, under President Biden, implemented new export controls in 2022. These restrictions were revised and significantly tightened in 2023. Given the challenges the U.S. has faced in maintaining its ‘small yard, high fence’ it is reasonable to ask how successful India will be if it were to adopt a similar approach in its engagement with China. Thirdly, it is imperative to keep in mind the Chinese reaction to the ‘high fence, small yard’ argument if India were to adopt such a rationale. When the U.S. implemented export controls, the Chinese reaction was swift and furious. At the time, the Chinese Foreign Ministry argued that the U.S. “abuses export control measures to maliciously block and suppress Chinese companies” so that the United States could “maintain its sci-tech hegemony.” Senior Chinese officials such as Wang Yi believe that the “U.S. was trying to contain China’s economic rise with its “small yard, high fence” export control strategy.” How might China react if India adopted a similar strategy? This is not to say that India should refrain from deploying a policy that is determined to be in its best interest. However, any policy would take into account the adversary’s reaction, and in this case, we have ample evidence of how China might react. The final point, which is crucial, is that the U.S.-China analogy being used to make a case falls short on a key measure: comparing the dynamic of the security relationship across the two relationships. No one will deny that U.S.-China ties are tense. However, while talking about tense security ties between India and China, we should remind ourselves that China discarded long-standing border agreements that had (relatively) kept the peace for over three decades (the 1993 and 1996 border agreements), destabilized the border, and engaged in acts that led to the deaths of 20 Indian soldiers. That “U.S. is even more upset with China than India” as the author notes can be contested, given the severe trust deficit, manifest in the 100,000 soldiers stationed in the harsh environment along the India-China border. This is not to dismiss the healthy, and honestly, much-needed, debate on what India’s engagement with China looks like. Rather, the point of this response is to question the premise on which (re)engagement with China is sought.

[3] The American Cancer Society defines a biosimilar (or a biosimilar drug) as a “medicine that is very close in structure and function to a biologic medicine.”

[4] This RBI-led survey “captures information on financial parameters and operations of the Indian companies having technical collaboration with foreign companies.” For the 2021-23 survey, 709 Indian entities participated in the survey, of which 356 entities reported 674 foreign technical collaboration (FTC) agreements.

[5] Bai, Barwick, Cao, and Li show how Chinese policy necessitating joint ventures in the auto sector results in domestic Chinese automakers adopting “quality strengths of their joint venture partners, consistent with learning and knowledge spillover” and note that “worker flows and supplier networks mediate knowledge spillover.”

[6] According to data by the Ministry of Commerce and Industry, the value of FDI inflows from China is lower: $2.45 billion (of the total FDI equity inflow) between April 2000 and December 2021 (representing 0.43 percent of the total share of FDI in this period).

[7] An example: Chinese solar firms suspended “some production in Southeast Asia” in June 2024 after a “U.S. tariff reprieve on solar panels from some Southeast Asian countries expired.” This Reuters article notes that the “tariffs aim to target shipments by companies found to be dodging U.S. duties on Chinese goods by finishing panels in Malaysia, Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam” and that “over 80% of U.S. solar imports have been coming from the four targeted countries, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence.”

[8] During a rally in Ohio in March, Trump addressed President Xi, stating that he “would hit cars made in Mexico by Chinese companies with a 100% tariff, double the levy he has previously said he would put on automobiles made south of the U.S. border.”

[9] The article Mr. Srivastava is referring to was published in the Business Standard on August 15. It should be read in its entirety, but the key argument he makes is: “We need to reduce business costs at every step, from start to port, and improve infrastructure and the ease of doing business. Without these changes, foreign investments will be limited and focus on basic assembly rather than deep manufacturing, increasing our dependence on China for critical supplies. Worse yet, investments may come to promote trading of Chinese goods or expanding presence of Chinese brands in India.”

[10] Hiroyuki Odagiri and Akira Goto argue that Japanese auto firms were able to keep up, and compete, with European and American automobile manufacturers because of reverse engineering, research & development, and government policies (such as financial incentives, procurements, and standard setting). See this chapter on the automobile sector in the edited volume Technology and Industrial Development in Japan: Building Capabilities by Learning, Innovation and Public Policy.

[11] In Race to the Swift: State and Finance in Korean Industrialization, scholar Jung-en Woo notes that the S. Korean government supported six strategic sectors starting in the 1970s – steel, machinery, nonferrous metal, petrochemicals, shipbuilding, and electronics.

[12] This Financial Times article documents how instead of “outsourcing” production to China, Apple started building up “a supply and manufacturing operation of such complexity, depth and cost that the company’s fortunes have become tied to China in a way that cannot easily be unwound.” The article notes that “over the past decade and a half, Apple has been sending its top product designers and manufacturing design engineers to China, embedding them into suppliers’ facilities for months at a time.”

[13] BYD, the Chinese auto giant that overtook Tesla to become the world’s largest electric vehicle (EV) company in January 2024, was founded by Wang Chuanfu. In this profile of the founder, Kevin Xu points out that Wang’s “penchant to reverse engineer” played a prominent role in BYD becoming the battery and EV giant that it is today.

[14] An Economist article from June 2024 documents how overcapacity in China has led to intense turmoil in the nation’s giant solar industry. The article quotes a Chinese solar company executive who estimates that “at least half of the businesses across the supply chain will go under.” This Rhodium Group research note on Chinese overcapacity points out that “systemic bias” in the form of Chinese intervention “toward supporting producers rather than households or consumers allows Chinese firms to ramp up production despite low margins, without the fear of bankruptcy that constrains firms in market economies.”

[15] A 2022 CSIS study on China’s industrial policy expenditure estimated (using a “conservative methodology”) China’s spending to be “at least 1.73 percent of GDP in 2019” which was equal to “more than $248 billion at nominal exchange rates and $407 billion at purchasing power parity exchange rates.” For comparison, “as a share of GDP, China spends over twice as much as South Korea” (which was the second-largest relative spender in the study’s sample), and “in dollar terms, China spends more than twice as much as the United States.”

[16] Tracing the ideological origins of deregulation, Reuel Schiller notes how scholars of deregulation, including Martha Derthick and Paul Quirk (authors of The Politics of Deregulation) recognized that “there was a shift in American political culture in the 1970s that was of fundamental importance to the success of the widespread deregulatory policymaking that began at the end of the decade.”

[17] Katelynn Harris, in this note for the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, points out that “at its peak in June 1979, manufacturing employment represented 22 percent of total nonfarm employment, but that share had fallen to 9 percent by June 2019.” In a journal article, Charles, Hurst, and Schwartz, highlight that between 2000 and 2017, manufacturing employment fell by “about 5.5 million jobs” in the United States, and “real manufacturing output” was “at least 5% higher” in 2018-19 than it was in 2000. The fall in manufacturing employment (from 25% in 1970 to 13% in 2000) and rise in manufacturing production (more than doubling from 1970 to 2000) was a “result of gains in production” and China’s imports had a limited, minimal impact according to N. Gregory Mankiw, the then Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers, under President G. W. Bush.

[18] Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson authored this scathing critique of Henry Kissinger’s China policy, noting that Kissinger orchestrated the United States “opening to China” and this story didn’t “end well for American workers.”

[19] Scholars have studied the “managed competition” within China’s industries, especially within state-owned enterprises (SOEs). In a World Politics journal article, M. Pearson notes that “pressure to increase market competition for China’s state-owned enterprises has come from the highest levels of government.” In this Journal of Contemporary China article, B. Naughton argues that “China’s policy-makers have built some competition into all the sectors in which state ownership is prominent” reiterating the idea of “managed competition.” In this Chinese Journal of Sociology article, Kyle Chan describes China’s system of “managed competition” within Chinese SOEs “that attempts to harness the forces of competition while intervening to ensure a robust field of capable competitors.”

[20] In Peijun Duan and Tony Saich’s reading, monopolies in the Chinese system “are part of the comprehensive structure of government authority.” Recognizing the dangers of monopolies, the Chinese government has undertaken steps to “catch out monopolistic business activity” including “anti-monopoly probes” in the auto, IT, and telecom sectors, to mixed results.

[21] A note on the Indian Trade Services on the DGFT website (publication date unknown) states that the “sanctioned strength of ITS, as on date, is 191, comprising of 72 posts of Assistant DGFT at JTS level, 44 posts of Deputy DGFT at STS level (inclusive of NFSG) 48 posts of Joint DGFT at JAG level and 26 posts of Additional DGFT at SAG level and 1 post at the HAG level.”

[22] ‘Press Note 3’ that revised India’s FDI policy to curb “opportunistic takeovers/acquisitions of Indian companies due to the current COVID-19 pandemic” was released in April 2020. The Galwan clash occurred in mid-June that year. While the clash solidified India-China tensions, the issuance of ‘Press Note 3’ has been ascribed to concerns about Chinese investors taking control of Indian entities (a February 2020 think tank report found that of 30 Indian unicorns, 18 received funding from Chinese investors). Santosh Pai talks about the impact of Press Note 3 and India-China trade ties post-Galwan in this insightful In Focus podcast episode.