India & the United States: Intelligence & defense ties

The state of bilateral ties in light of recent intel revelations and developments in joint defense production

Summary:

This article focuses on intel and defense ties between India and the United States.

Recent revelations by a senior Indian official on intelligence sharing and certain developments in joint defense production raise interesting questions about the state of bilateral ties.

One of the most striking aspects of the Indian defense imports landscape has been the diversification of its arms supplies [see Fig. 2 & 3]

While certain strides in India-U.S. defense ties need to be (and are being) appreciated, in an effort to push the policy conversation forward, I leave the readers with two questions around the bilateral relationship: i) what lessons have been drawn from previous attempts at joint defense projects, and ii) how do you manage expectations in a relationship where defense ties are doing the heavy lifting?

Introduction:

At an event on February 21, 2024, India’s Defense Secretary, Giridhar Aramane, made some interesting remarks –

“India is giving a face-off to our (northern) neighbour in almost all the fronts we have with them… we are standing against a bully in a very determined fashion. And we expect that our friend, the U.S. will be there with us in case we need their support.”

The Defense Secretary was referring to India’s neighbor, China (the “bully”), and speaking about growing India-U.S. cooperation against a common challenge. India and China have been engaged in a border stand-off since 2020 when the two sides clashed along a disputed border.

This is very much a live issue. On March 7, 2024, Sudhi Ranjan Sen reported on the deployment of 10,000 additional Indian soldiers to the India-China border –

“A 10,000-strong unit of soldiers previously assigned to the country’s western border has now been set aside to guard a stretch of its frontier with China, said senior Indian officials who didn’t want to be named because discussions are private.”

This deployment of 10,000 soldiers is in addition to the 50,000 soldiers that were repositioned to patrol the India-China border in 2021.

Given this background, the Defense Secretary’s remarks are interesting for two reasons. The first is the acknowledgment of intelligence coordination between India and the United States with respect to China by a senior Indian official. The Secretary’s remarks are also noteworthy because of the forum where he made the above-quoted statement – at the second India-U.S. Defense Acceleration Ecosystem (INDUS-X) summit.

In this article, I will provide some context to the Secretary’s remarks and explain how the two factors highlighted above: i) intelligence support from the United States, and ii) the significance of INDUS-X, can help shed light on the evolving India-U.S. bilateral relationship.

Intelligence sharing between India & the United States –

An aspect of the “support” that the United States was providing to India, according to the Defense Secretary, was intelligence sharing. The Secretary noted that “intelligence, the situation awareness, which the U.S. equipment and the U.S. government could help us with” was helpful in the context of the India-China border clash.

This reflection on the intel support that the United States is providing India is worth examining as it is coming from India’s top bureaucrat in the Ministry of Defense (MoD). Thus far, details about the kind of intelligence cooperation between India and the U.S. remained largely in the background, with the occasional report or media article shedding light on this.

In 2020, when India and China clashed at points along the disputed border, U.S. support for India was seen to be crucial. Writing about how the U.S. supported India during this border flare-up, Lisa Curtis and Derek Grossman note –

“The United States provided information and intelligence and expedited delivery of equipment, including two MQ-9B surveillance drones and winter gear. U.S.-India relations deepened as a result of the U.S. response, and senior Indian officials have noted privately that U.S. support for India during the crisis had a profoundly positive impact on India’s ability to defense its borders.” [emphasis added]

In October 2020, India and the United States signed a major agreement (the last of four ‘foundational’ defense agreements) – the Basic Exchange and Cooperation Agreement (BECA) for Geospatial Intelligence. The agreement was signed against the backdrop of heightened India-China tensions (following the border clashes) and came after officials from India and the United States spent more than a decade negotiating the terms of the agreement.

As a CRS report notes,

“U.S. law requires that certain sensitive defense technologies can only be transferred to recipient countries that have signed a CISMoA [Communications Interoperability and Security Memorandum of Agreement; the third ‘foundational’ agreement that India & U.S. signed in 2018] and/or BECA.” [emphasis added]

In a Brookings Institution report, Joshua White stated –

“The signing of the BECA, a broad framework agreement, enables both parties to establish more specific arrangements relating to sharing classified and controlled unclassified information. The exchange of sensitive maritime information on subjects such as Chinese submarine transit of the Indian Ocean, and geospatial data pertaining to the disposition of Chinese forces along the Sino-Indian border, are two natural areas on which to pursue such arrangements.” [emphasis added]

The utility of the United States’ intelligence and information sharing surfaced in a media report in March 2023. In a U.S. News article, sources revealed that –

“India was able to repel a Chinese military incursion in contested border territory in the high Himalayas late last year [2022] due to unprecedented intelligence-sharing with the U.S. military, U.S. News has learned, an act that caught China’s People’s Liberation Army forces off-guard, enraged Beijing and appears to have forced the Chinese Communist Party to reconsider its approach to land grads along its borders.” [emphasis added]

The report further noted –

“The U.S. government for the first time provided real-time details to its Indian counterparts of the Chinese positions and force strength in advance of a PLA incursion, says a source familiar with a previously unreported U.S. intelligence review of the encounter into the Arunachal Pradesh region. The information included actionable satellite imagery and was more detailed and delivered more quickly than anything the U.S. had previously shared with the Indian military.” [emphasis added]

The impact of this intelligence sharing? From the U.S. News article – “Indian forces identified the Chinese positions using the intelligence provided by the U.S. and maneuvered to intercept them.” This resulted in a “Chinese retreat.” The basis of this intelligence-sharing was the BECA. The fact that India and the United States had signed this agreement is public knowledge. Crucially, as per sources, “the follow-through of actually sharing intelligence to actionable effect has not been previously reported”. [emphasis added]

Given this background on intelligence sharing, the Defense Secretary’s remarks on intel cooperation between India and the United States – the first from an official Indian source – are striking.

One of the sharper reactions to the Secretary’s remarks has come from a former senior Indian diplomat. Writing on the India-U.S. relationship and reacting to the Secretary’s remarks, Shyam Saran, former Foreign Secretary of India (2004-06) wrote –

[The Defense Secretary’s] “remarks, which appear to openly solicit US support as a supplicant in helping India cope with the continuing military standoff with China on the border, are unusual. They may not have been appropriate to the occasion and even convey, perhaps inadvertently, that India is not capable of dealing with the Chinese threat on its border on its own. The US Department of Defense’s readout on the meeting contains neither a reference to these remarks nor any reaction from the US Indo-Pacific Commander.” [emphasis added]

Amb. Saran’s point about how China perceives India-U.S. ties has been highlighted by close observers of Indian foreign policy. For instance, in an interview I conducted with former Foreign Secretary Vijay Gokhale, he noted [16:20 mins onwards] –

“[Indians] were seen [by the Chinese] in terms of either positive or negative depending on which relationships we had with the other two major powers. If we swung too close to any of them whether it was the Soviet Union in the 70s or the United States in the 50s or the United States today, the Chinese considered India to be a problem or a threat. If we remained relatively balanced as was the case in the 1980s or 1990s, the Chinese considered us not relevant to their foreign policy because we didn’t represent a threat, and therefore there was no effort to engage us in the same bilateral framework that we [Indians] were intent on engaging the Chinese.” [emphasis added]

The big picture question going forward will hinge on how the triangular relationship between India, China, and the United States evolves.

INDUS-X –

In addition to the import of intelligence sharing between the two states, the forum at which the Defense Secretary made these remarks is worth examining. As noted, he was speaking at the second INDUS-X summit.

INDUS-X, launched on June 21, 2023, by the Indian MoD and the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD), “went relatively unnoticed” at the time of its launch according to two scholars. This is largely because India and the United States made several joint announcements during Indian Prime Minister Modi’s official state visit to D.C. in June 2023.[1]

What is the INDUS-X? It aims to “expand the strategic technology partnership and defense industrial cooperation between our [Indian and U.S.] governments, businesses, and academic institutions.” This builds on the January 2023 U.S.-India initiative on Critical and Emerging Technology (iCET) that was announced by the National Security Advisors of the two nations.

Why does the INDUS-X matter? India and the United States have been strengthening bilateral ties for over two decades now. Notwithstanding current headlines, this is a relationship that has been fostered and tended to by both political parties in the United States, and by the Indian National Congress (INC; the current primary opposition party in India) and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP; the current ruling party), when in power.

As in any state-to-state relationship, ties have waxed and waned at times, but the overall trajectory has been one of greater engagement. A crucial aspect of this relationship has been defense ties. India, the world’s largest importer of major arms (according to a 2023 SIPRI report) has traditionally relied on the Soviet Union, and subsequently, Russia for its defense needs.

However, India has made attempts to diversify its sources of arms. For instance, from 2013 to 2017, and then from 2018 to 2022, Russia remained the top supplier of arms to India. However, during these two periods, Russia’s “share of total Indian arms imports fell from 64 per cent to 45 per cent” [see Fig. 1]. According to the 2023 SIPRI report –

“Russia’s position as India’s main arms supplier is under pressure due to strong competition from other supplier states, increased Indian arms production and, since 2022… constraints on Russia’s arms exports related to its invasion of Ukraine.” [emphasis added]

Fig. 1. Indian arms imports from Russia (as % of India’s total imports) for select time periods (Source: SIPRI reports; 2009-13; 2014-18; 2019-23)

While Russia’s share of total Indian arms imports has fallen, India’s arms imports from France increased by a stunning 489 percent between 2013-17 and 2018-22. India is now the top importer of weapons from Russia, France, and Israel.[2]

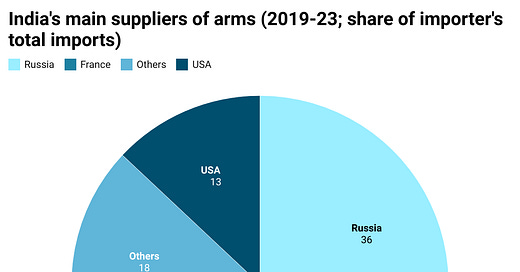

A snapshot of India’s main suppliers in the 2009-13 period, and then in the 2019-23 period [see Fig. 2 & 3] illustrates the underlying change that is taking place in how India is procuring arms –

Fig. 2 & 3. India’s main suppliers of arms (2009-13 & 2019-23; share of importer’s total imports)

What is the state of India-U.S. defense sales? In 2004, the value of India’s arms imports from the United States was relatively small compared to India’s overall imports (or even when compared to the United States’ total arms exports). Dinshaw Mistry pointed out the change in US arms sales to India –

“From 2001 to 2004, New Delhi’s arms imports from the United States were $400 million… Over the next four years, 2005 to 2008, New Delhi’s military procurements from the US increased to over $3 billion… From 2009 to 2013, India’s defense orders from US firms, some of which are pending finalization, were worth $11 billion.”

According to the DoD, between 2008 and 2023, “India has contracted for nearly $20 billion worth of U.S.-origin defense articles.” Given India’s status as the top importer of arms, and the changing India-U.S. defense sales relationship, INDUS-X could arguably portend an inflection point in bilateral defense ties. While it may appear premature to place such heavy expectations on INDUS-X given that the initiative is not even a year old, there are promising signs.

INDUS-X has already instituted processes that are deepening defense ties. A factsheet released following the second INDUS-X summit pointed to this. Some achievements include designing and selecting winners for joint defense challenges (two sets of winners won $300,000 and $900,000 each), crafting an education series to help defense companies harness private capital and navigate export controls, and organizing investor strategy sessions to foster joint innovation funding for Indian and U.S. companies.

The factsheet also highlighted the ambitious path that the two countries have carved out going forward. This includes setting up academic partnerships between premier educational institutions in the two countries, providing defense companies access to state-of-the-art testing ranges, and instituting advisory forums. Crucially, INDUS-X has managed to address regulatory challenges.

As Sameer Lalwani and Vikram Singh note –

“Both governments have engaged with industry to better evaluate the costs and benefits of the regulatory environment on both sides – including export, disclosure and procurement rules that might hamper collaborative innovation and the diversification of supply chains.”

Reflecting on India-U.S. ties –

Defense Secretary Aramane’s remarks prompted me to explore two facets of the India-U.S. relationship. Official acknowledgment of intel cooperation between India and the United States, along with an intensified focus on bilateral defense industrial cooperation are worth examining given the ongoing changes in the geopolitical order.

India-U.S. defense ties have undergone massive changes from two decades ago. Senior Indian and American officials have noted this transformation. In June 2023, a senior DoD official noted –

“The United States and India are increasingly doing things in their defense partnership that people wouldn’t have said was possible 20 years ago… For instance, 20 years ago, there were no U.S. defense sales to India at all, the official said. Now, we’re talking about co-producing and co-developing major systems together.” [emphasis added]

Shyam Saran, the former Indian Foreign Secretary, also made comments in a similar vein in a recent conversation on Indian foreign policy [34:00 mins onwards] –

"The level of engagement between the security and defense establishment of the US and India ... If you had asked me when I was Foreign Secretary [2004-06] whether India-U.S. relations would reach this level... I would have said this is not possible at all..." [emphasis added]

Rather than further highlight (or speculate about) what closer intel cooperation and defense industrial production mean for India and the United States, I would like to leave the reader with two questions –

1. What lessons have the two countries drawn from previous attempts at joint defense industrial projects?

INDUS-X is designed to “expand the strategic technology partnership and defense industrial cooperation between” several stakeholders in the two countries. As noted above, in less than a year, INDUS-X has already instituted mechanisms that will be beneficial to the India-U.S. relationship. However, it is crucial to note that this isn’t the first time the two nations have attempted such collaboration.

iCET, and INDUS-X by extension, build on a similar joint endeavor – the 2012 Defense Trade and Technology Initiative (DTTI) – that failed by most accounts. According to Rahul Bedi –

“DTTI had languished and eventually perished due to enduring shortcomings by the respective entities responsible for furthering it. This included vacillation in decision-making by the Ministry of Defense (MoD) and ‘unilateralism’ by the US undersecretary of defense for acquisition, technology and logistics [USD (AT&L)], in patronizingly offering Delhi low-grade technologies.” [emphasis added]

Another report notes that –

“the DTTI seemed to fizzle out due to a general lack of urgency and insufficient top-down pressure to overcome the mismatches in expectations and bureaucratic procedures.” [emphasis added]

Even before the DTTI, there had been talk of joint Indo-U.S. defense production. For instance, roughly two decades ago in 2005, India –

“emphasized a desire that security commerce with the United States not be a “buyer-seller” interaction, but instead should become more focused on technology transfers, co-development, and co-production.” [emphasis added]

Given this uneven legacy of previous attempts at joint development and production of defense systems, a key question is: what lessons have the two countries drawn from these experiences as they chart out a future for iCET, and INDUS-X?

This isn’t a cynical take on India-U.S. defense initiatives. After all, it is not an easy task for actors to work through the complex labyrinth of the U.S. military-industrial complex, the Indian bureaucratic structure, or domestic and international regulatory landscapes. Furthermore, India, an emerging market, has limited resources and massive developmental needs and thus needs to make hard choices about resource allocation.

Given these realities, it is perhaps important for policymakers in the two countries to reflect on previous attempts at joint defense production, and potentially craft a ‘lessons learned’ document. This can help stakeholders in public institutions and private entities from both India and the United States better navigate joint defense development and production going forward.

2. How do you manage expectations in a relationship where defense ties are doing the heavy lifting in the bilateral dynamic?

To observers outside the policy-making space, India-U.S. ties might appear to be largely driven by security considerations, and to a certain extent, the logic of people-to-people ties. The security angle of the bilateral relationship becomes all the more pertinent given the current geopolitical moment. India, and the United States, are much more aligned on the challenges posed by China. While the growth in defense ties should be (and is being) lauded, how does one manage expectations in the relationship when there is a clear imbalance?

Experts have pointed out that while the two countries have been making remarkable strides in the defense domain, serious differences on trade, intellectual property, and immigration issues persist. Therefore, while growth in defense ties between India and the United States can be observed in a two-decade-long period, the same can’t be said for some of the key sticking points in the relationship.

A CRS brief on India-U.S. ties from June 2023 stated –

“More engagement has meant more areas of friction in the partnership, including some that attract congressional attention. India’s economy, while slowly reforming, continues to be a relatively closed one, with barriers to trade and investment deterring foreign business interests… Differences over U.S. immigration law, especially in the area of nonimmigrant work visas, remain unresolved. India’s intellectual property regime comes under regular criticism from U.S. officials and firms... Meanwhile, cooperation in the fields of defense trade, intelligence, and counterterrorism, although progressing rapidly and improved relative to that of only a decade ago, runs up against institutional and political obstacles.” [emphasis added]

Similarly, Joshua White argued the following in a 2021 Brookings report –

“Even as defense ties have advanced, the overall bilateral relationship has become notably imbalanced, with other key areas of cooperation characterized by friction or indifference. Notwithstanding some positive developments in energy trade and private sector investment, bilateral trade negotiations have ground to a standstill, thwarted by the Trump administration’s embrace of protectionism at home and a crude transactionalism abroad, as well as a renewed push in New Delhi to protect domestic industries…. At the same time that security cooperation has become perhaps the principal load-bearing pillar of the bilateral relationship, a chorus of voices in Washington, from both the left and the right, have begun more vocally expressing anxieties about whether the value and sustainability of U.S. engagement with India has been oversold.” [emphasis added]

The CRS and Brookings Institution report both highlight the sharp disagreements between India and the United States on issues such as trade and IP. This is not to say that any of the differences between the two sides will necessarily turn into non-negotiable disputes. Respective officials from the Biden and Modi administrations have reportedly established a rapport and moved the needle on some thorny trade issues. For instance, the resolution of long-standing WTO trade disputes between India and the United States in June and September 2023 points to some of the progress that the two states have made.

In raising the two questions above – i) what lessons have been drawn from previous attempts at joint defense projects, and ii) how do you manage expectations in a relationship where defense ties are doing the heavy lifting – the aim is to productively push the policy conversation for one of the most consequential bilateral relationships. Even as India and the United States continue to make remarkable strides in the defense bilateral relationship, it is crucial to shine a light on aspects of the relationship that deserve greater scrutiny.

[1] One of the crucial announcements made at the state visit – an “MoU between General Electric and Hindustan Aeronautics Limited [HAL] for the manufacture of GE F-414 jet engines in India, for the Hindustan Aeronautics Limited Light Combat Aircraft Mk 2.” The statement noted: “The leaders [Indian Prime Minister Modi and U.S. President Biden] committed their governments to working collaboratively and expeditiously to support the advancement of this unprecedented co-production and technology transfer proposal.” [emphasis added]

[2] India is also the second-largest importer of weapons for South Korea, and third-largest for South Africa.

very well defined, keep it up